ABOUT 40% of American voters have valid concerns about 2020 election security and about 30% expect foreign interference. Even more disturbing are the ongoing attacks on our constitutional rights and liberties regarding voting and the fair representation of all the residents of the United States in the U.S. Congress as well as state assemblies. Once again it is the republican party taking court and legislative action to guarantee White Americans are able to maintain control of our nation, they want to turn back time in America. (NOT MY) pres drumpf / trump and (NOT MY) vice-pres pence, with their administration are brazenly leading this effort on behalf of their fascist, neo-nazi constituency, in doing so they reinforce the importance of the 2020 elections because when drumpf / trump-pence are defeated and Democrats are elected to the White House and are the majority in both the U.S. House and Senate this threat to our democratic Republic can be stopped. "This stealth campaign to redraw the political map has raised the already high stakes for the 2020 election, in which the Democratic Party is trying to win back state houses to reverse the GOP’s redistricting edge. And a Democratic president could try to stop the reapportionment scheme in its tracks by blocking the release of citizenship data. (Elizabeth Warren has pledged to do this if elected president, as did Cory Booker and Julián Castro when they were still candidates.)" From Mother Jones and Fresh Air / NPR.....

Trump's Stealth Plan to Preserve White Electoral Power

For the past decade, Republicans have sought to exclude noncitizens from the redistricting process. Now Trump was going even further.

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2020

Two days after Tropical Storm Imelda battered her district in Houston, state Sen. Carol Alvarado drove from its heavily Latino east side, past taquerias and signs for immigration attorneys, to another predominantly Latino neighborhood just north of the downtown skyline.

Senate District 6 is shaped like a dragon whose head starts in the city’s industrial outskirts while its body snakes and stretches into its center. She arrived at a red, Southwestern-style building that houses a community center named after Leonel Castillo, who led a boycott of the city’s segregated schools in 1970 and became the first Latino elected to citywide office. As she went to the podium to address more than 100 of her constituents, Alvarado praised Castillo as “a trailblazer who paved the way for so many of us, like myself, to be able to run for office.”

Listen to Ari Berman talk with President Barack Obama’s attorney general Eric Holder, about some of the most insidious voter suppression tactics across the country, in a wide-ranging conversation moderated by Broad City star Ilana Glazer, on this episode of the Mother Jones Podcast. (CLICK HERE)

The daughter of a cement worker with a third grade education, Alvarado grew up in Manchester, a Latino neighborhood squeezed between the train tracks, the freeway, and the port of Houston. Rail cars frequently blocked the main road leading into the area. Her school playground overlooked massive chemical tanks and oil refineries that billowed gray smoke. Residents of the neighborhood breathe some of the dirtiest air in Texas and suffer from some of its highest cancer rates. Her 92-year-old mother still lives there, next to the Catholic church that Alvarado attends on Sundays. She got involved in politics “because of where I lived,” the 52-year-old Democrat told me over beef enchiladas at the community center. “I saw what was going on around me. It pissed me off.”

She joined the City Council, then the state House of Representatives, where she served five terms, and was elected to the state Senate in a special election in December 2018. Despite being outnumbered by Republicans in Austin, she’s proved to be a skilled legislator, helping pass 32 bills in the 2019 legislative session, and securing more funding for schools, flood protection, and mammograms. “You’re getting a very good return on investment from me,” she said jokingly at the meeting.

Even in the best of times, serving this district is a big job. Alvarado represents over 850,000 people—about 100,000 more than a typical member of Congress. After highlighting her legislative successes, Alvarado talked about the bills that would have been vital for her district if her Republican colleagues had not blocked them: One in five residents of Harris County are uninsured, but the legislature refused to expand Medicaid; Texas has some of the lowest voter turnout rates in the country, but it won’t adopt online voter registration; despite the recent mass shootings in El Paso and Santa Fe, Alvarado couldn’t pass a single one of her gun control bills.

These hot-button issues were a mere prelude to the fight to come. “The next session, as we move forward, the redistricting process will dominate,” she said, referring to the once-in-a-decade exercise of redrawing the state’s legislative boundaries that will follow the 2020 census. “The census gives us the numbers, we take those numbers, and then we use that during the redistricting process.” But if President Donald Trump’s GOP has its way, 2021 could be the year Texas and other Republican-controlled states upend the traditional way of counting who gets represented by state legislators. This could radically transform districts like hers, undoing decades of demographic change and disempowering lawmakers of color like Alvarado. And it would be a dramatic win for the conservative war on voting rights, allowing Republicans to game the system by consolidating electoral power they can’t win at the ballot box.

Ben Giles

On July 11, a visibly agitated Donald Trump appeared in the White House Rose Garden to announce that his administration was dropping its bid to add a citizenship question to the 2020 census. The Supreme Court had blocked the plan two weeks earlier, with Chief Justice John Roberts writing that the administration’s claim that the question was needed to better enforce the Voting Rights Act “seems to have been contrived.” Civil rights groups said such a question would spark fear that the information would lead to deportations, causing a severe undercount of immigrant communities. Census Bureau researchers predicted it could lead to 9 million people not filling out the census. But, Trump said defiantly, “I’m here to say we are not backing down on our effort to determine the citizenship status of the United States population.”

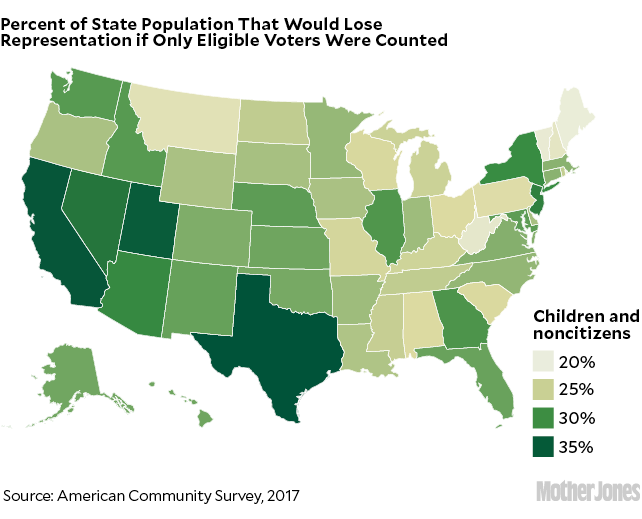

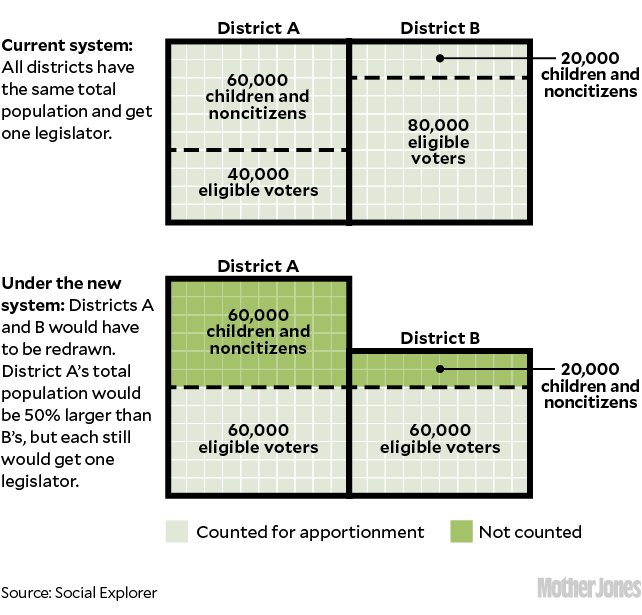

Trump then made a move that could still turn citizenship data into a political tool to boost the influence of white Republican areas. He announced an executive order calling on federal agencies to send all existing information on who is and isn’t a citizen to the Department of Commerce, which oversees the Census Bureau. Trump suggested how those details might be used: “Some states may want to draw state and local legislative districts based upon the voter-eligible population.” For the past decade, Republicans have sought to exclude noncitizens from the redistricting process. Now Trump was going even further, suggesting that anyone who is not eligible to vote, including children, did not have to be counted toward apportioning representation at the state and local level.

It’s long been a bedrock principle of American democracy that elected officials represent all of their constituents, whether or not they are eligible to vote. Almost all congressional and state legislative districts are drawn based on their total populations, including voters and nonvoters, citizens and noncitizens, adults and kids. Yet while the 14th Amendment requires that congressional districts are based on total population, the Supreme Court has never definitively ruled on what the standard should be for state districts, although since the 1960s nearly all states have counted everyone. Drawing state legislative districts based on eligible voters instead of total population would be a huge win for Republicans, who tend to represent areas with fewer noncitizens. Democrats currently hold all of the 50 upper state House seats with the highest percentages of foreign-born noncitizen residents.

Using the voting-eligible population as the metric for reapportionment could lead to half of all state legislative districts in the country being redrawn. Those new districts would exclude up to 55 percent of Latinos, 45 percent of Asian Americans, and 30 percent of African Americans from being counted as constituents—compared to 21 percent of white people, according to the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. As the group argued in a legal filing in 2015, “This would amount to a massive shift in political power away from groups that are already disadvantaged in the political process and further concentrate power in the hands of a white plurality that does not adequately represent the full diversity of the total population.”

That seems to be the point. Thomas Hofeller, the late Republican gerrymandering mastermind who played a central role in the push for the citizenship question on the census, wrote in a 2015 study, commissioned by the conservative news site Washington Free Beacon, that redrawing districts based on the voting-age citizen population “would clearly be a disadvantage to the Democrats” and “advantageous to Republicans and Non-Hispanic Whites.” (The document came to light after Hofeller’s estranged daughter turned over his hard drives to Common Cause as part of a lawsuit challenging gerrymandered maps he’d drawn in North Carolina.) In Texas, such a shift would leave almost 2.7 million noncitizens and 7 million children without political representation, according to census data compiled by the state’s Hispanic legislative caucus.

No Senate district in the state would be affected more than Alvarado’s. More than half of her constituents cannot vote—30 percent are under 18, and 22 percent are adult noncitizens. Because the US Supreme Court has ruled that districts must be roughly equal in population, Alvarado’s district would have to be redrawn, potentially adding hundreds of thousands of new voters so she’d have the same number of voters as other districts with fewer children or noncitizens, causing her district to grow to more than 1 million people. The district might be “packed” or “cracked”: It could swell with more Democratic voters, weakening the party’s representation elsewhere, or it could take in thousands of Republican-leaning voters, diluting its Latino majority and possibly costing Alvarado her seat. “If I have to absorb hundreds of thousands of people, that’s going to change the dynamics of the district,” she told me. “And it changes all the adjoining districts.”

If Texas takes Trump up on his offer to use federal data to only count voters, it would have profound consequences. Democrats need only nine seats to regain control of the Texas House of Representatives for the first time since 2002, but redrawing districts based on eligible voters would keep the state solidly red, shifting eight or more seats back to the GOP, according to an analysis by Andrew Beveridge, a professor of sociology at Queens College in New York. In the past year, Texas has gained about nine Latino residents for every white resident, and only 34 percent of the state’s kids are white. These demographics should help Democrats when new maps are drawn in 2021. But excluding children and noncitizens from the count would radically reduce the impact of demographic change. Moreover, the year 2021 will be the first time in half a century that Texas and other states with a history of racial discrimination will not have to get their redistricting maps approved by the federal government under the Voting Rights Act. These changes, combined with a recent Supreme Court decision that federal courts cannot review partisan gerrymandering, could lead to an unprecedented effort by Republican-controlled states to weaken Democratic power and sideline communities of color.

“I represent everybody,” said Texas state Sen. Carol Alvarado. “People are people.”

Sandy Carson

Under this new system, heavily Latino districts in Houston, Dallas, and South and West Texas would likely be dismantled, with their electoral power redistributed to white strongholds. The Texas legislature would see its lowest level of Latino representation since the 1980s. And if this change were adopted nationwide, the number of Latino state legislators could decline by 12 percent, according to Carl Klarner, a political scientist and elections forecaster. “It would dramatically diminish Latino voting power,” says Thomas Saenz, president and general counsel of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, which has filed suit against the executive order. “It’s a power grab,” Beveridge said. “If they were able to do this, they would take the country back in time.”

At the center of the effort to redefine political representation is Edward Blum, the conservative activist who organized the successful challenge to the Voting Rights Act in 2013 and has been trying to overturn affirmative action at Harvard. Blum sued Texas in 2014 to force it to draw state Senate districts based on citizens or eligible voters. The Supreme Court shot him down, but it left an opening that Trump walked through with his executive order. Blum predicts that “many states, counties, cities, and other jurisdictions will explore using a population metric other than total population in the upcoming redistricting cycle.”

Blum told me that Republican officials and political consultants in Texas, Arizona, Florida, Tennessee, and Missouri have already called him. “I’m not involved in Republican electoral politics. However, my phone rings a lot from people who are,” Blum said. “This is being discussed. This is on everyone’s radar…So many attorneys general, so many heads of redistricting committees in state legislatures are aware of this.” In February 2019, Missouri Republicans introduced legislation to draw their state’s districts based on “one person, one vote,” widely assumed to mean something other than total population. Alabama has sued the Census Bureau to exclude undocumented immigrants from counting toward congressional apportionment.

Blum’s effort is backed by Hans von Spakovsky, a Heritage Foundation senior fellow and a former member of Trump’s disbanded election integrity commission, who has led the push for voter ID laws and other voting restrictions. Von Spakovsky has long perpetuated the myth of widespread voter fraud and played an instrumental role in purging longtime civil rights lawyers from the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division while serving as a top lawyer there under George W. Bush. In August 2019, von Spakovsky spoke on a panel about redistricting in Austin at the annual meeting of the American Legislative Exchange Council, the conservative group that writes model legislation in conjunction with corporate interests. “All of you need to seriously consider using citizen population to do redistricting,” he told 200 Republican state legislators. He explained why: “The higher the number of noncitizens in a district, the greater the chances they’re going to vote for a liberal. The higher the number of citizens in a district, the higher the chances they’re going to vote for a conservative.” (Cleta Mitchell, a conservative lawyer who spoke alongside von Spakovsky, urged the lawmakers to destroy their notes from the conference so they couldn’t be cited in future lawsuits.)

This stealth campaign to redraw the political map has raised the already high stakes for the 2020 election, in which the Democratic Party is trying to win back state houses to reverse the GOP’s redistricting edge. And a Democratic president could try to stop the reapportionment scheme in its tracks by blocking the release of citizenship data. (Elizabeth Warren has pledged to do this if elected president, as did Cory Booker and Julián Castro when they were still candidates.)

Alvarado fumed when she thought of what might happen to her district if only eligible voters were counted. “I represent everybody,” she said. “Children can’t vote, but I represent them. I go to the Capitol during the session and a priority is education.” It was “a bunch of BS” that noncitizens also might not be counted as constituents. “People are people, whether they were born here or they migrate here. We welcome them. They are part of our community.” She said Democrats in the Texas legislature are on high alert. “We’ve been talking about it and we’re concerned about it. I’m sure it’s going to be debated heavily—what numbers do we look at when we’re drawing the maps? Is it the [citizen] population? Is it all people? And that’s why the 2020 election is going to be so important.”

The fight over who gets counted is as old as the United States itself. Fair representation was one of the founding principles of the new republic. “No taxation without representation” was a core principle of the revolution, which was followed in Great Britain by a revolt against the “rotten boroughs” of the British Parliament, where absentee lords representing as few as a dozen people received more seats than growing industrial cities like Manchester and Birmingham. Even though most of the newly formed states denied the vote to women, black people, and propertyless white people, some founders believed everyone was entitled to political representation. “There can be no truer principle than this—that every individual of the community at large has an equal right to the protection of government,” Alexander Hamilton said at the Constitutional Convention.

Of course the democratic institutions the founders created often fell short of these ideals. Small states had more power than large ones in the Senate, and slave states had more power than free ones in the House because enslaved African Americans were counted as three-fifths of a person for purposes of representation. And both small states and slave states had disproportionate power in the Electoral College.

When the post–Civil War slate of constitutional amendments was being debated in 1865 and 1866, some radical Republicans, led by Rep. Thaddeus Stevens, proposed apportioning House seats based on “legal voters” instead of total population. They predicted—correctly—that newly emancipated African Americans would be disenfranchised yet still counted by former slave states seeking to grab even more power than they’d had under the three-fifths clause. But other pro-Reconstruction Republicans argued that, despite this prediction, nonvoters such as women and children were also entitled to representation even if they could not vote. “No one will deny that population is the true basis of representation; for women, children, and other nonvoting classes may have as vital an interest in the legislation of the country as those who actually deposit the ballot,” said former House speaker Rep. James Blaine of Maine.

In the end, the 14th Amendment stated that “Representatives shall be apportioned…counting the whole number of persons in each State.” That settled the issue at the federal level for a while, but in the 1920s, after the country’s population shifted from rural to urban areas following a wave of immigration, nativist politicians sought to exclude noncitizens from counting toward congressional apportionment. Rep. William Vaile of Colorado said he wanted to count a “more distinctly American population,” since at the time of the 14th Amendment, the number of immigrants “had not become sufficiently noticeable to be recognized as a danger or an evil.”

After the 1920 census showed that more Americans lived in urban areas than rural ones, Congress refused to reapportion its seats based on the new numbers for the first time in US history. Throughout the ’20s, rural legislators sought to pass a constitutional amendment excluding noncitizens from congressional apportionment, but liberals like Rep. Fiorello LaGuardia of New York argued persuasively that all inhabitants were entitled to equal representation. “The exclusion of aliens is only the first step in getting away from a popular and constitutional government of free men,” LaGuardia said on the House floor. “Perhaps this is only the entering wedge—first to exclude aliens from the count. And then the next step will be to exclude those who do not own property; and then the next step will be to exclude all those who do not own real property, until the government will be controlled entirely by a small privileged class, as it was in England at the time of the American Revolution.” Still, the House didn’t adopt a new congressional map that reflected the changing population until 1929.

Total population would remain the basis for allocating House seats, but state legislative officials had far more leeway. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, conservative white legislators drew political districts with wildly unequal populations to give more influence to lawmakers from rural areas. This advantage was locked in by amending state constitutions or by simply ignoring the constitutional requirement to redraw legislative districts every 10 years to account for population change.

In the 1930s, “In the typical state, just 37 percent of the population elected a majority of seats in at least one chamber,” write political scientists Stephen Ansolabehere and James M. Snyder Jr. in The End of Inequality: One Person, One Vote and the Transformation of American Politics. A 1926 amendment to California’s constitution specified that no county could have more than one state Senator, which meant that by 1960 the 6 million people of Los Angeles County had the same number of senators—one—as a district with 14,000 residents spread across three counties east of the Sierras. The distribution of representation became so skewed that it was possible for just 10 percent of Californians to elect a majority of the state Senate. The stacked deck of yesterday makes the gerrymandering of today look tame.

The Supreme Court struck down this system of rural minority rule in a series of “one person, one vote” cases in the early 1960s, ruling that state legislative and congressional districts must be roughly equal in population and “apportioned on a population basis.” This shifted power from sparsely populated areas to the urban and suburban population centers where Americans increasingly lived. “The fundamental principle of representative government in this country is one of equal representation for equal numbers of people, without regard to race, sex, economic status, or place of residence within a State,” Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote for the majority in Reynolds v. Sims. As he pithily put it, “Legislators represent people, not trees or acres.” Of all his landmark rulings, Warren considered this transformation of democratic representation his most important achievement on the court.

That might have been the end of the issue if not for Edward Blum.

In 1997, Houston created four majority-minority City Council districts, two in heavily black areas and two in heavily Latino areas. The city had recently annexed a wealthy white planned community called Kingwood. The city connected Kingwood to a district in Clear Lake City, a similar planned community about 40 miles away, maintaining the surrounding majority-minority districts. Blum, a former stockbroker who lived in Houston and ran unsuccessfully for Congress in 1992, filed suit in federal court against the redistricting plan, alleging it was an illegal racial gerrymander. Yet he also noticed that predominantly nonwhite districts had greater numbers of noncitizens and fewer eligible voters than the adjoining predominantly white districts. He thought this gave voters in districts with more people of color a more powerful vote, since it took fewer eligible voters to elect a candidate there, which he said didn’t “represent the spirit of ‘one person, one vote.’” He argued that Houston should draw its City Council districts based on eligible voters rather than total population.

Blum lost in district court and on appeal. In 2001, the Supreme Court declined to hear the case, but Justice Clarence Thomas dissented, believing that Blum’s argument about population counts had merit. Thomas left the door cracked for Blum to come back to the high court.

Blum turned his attention to challenging the Voting Rights Act and affirmative action, but kept the population issue on the back burner. In 2014, he sued Texas to force it to draw its state Senate districts based on eligible voters. Blum recruited Sue Evenwel as his lead plaintiff, a tea party activist who lived in a red district with a small number of noncitizens. As the chair of the Titus County GOP, she claimed that the current system was designed to give “equal representation to a block of undocumented people who are not eligible or registered to vote.” Her co-plaintiff was a Christian fundamentalist who claimed the Earth is the center of the universe and that unicorns are real. They asserted that, by counting nonvoters to apportion seats, Texas was denying “eligible voters their fundamental right to an equal vote.”

The Supreme Court took the case, and in 2016 it unanimously ruled that Texas could not be forced to abandon total population if it didn’t want to. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote a majority opinion joined by five justices, including Chief Justice Roberts, that strongly suggested states should count all constituents, not just voters, when drawing legislative districts. “As the Framers of the Constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment comprehended, representatives serve all residents, not just those eligible to vote,” Ginsburg wrote. “Nonvoters have an important stake in many policy debates and in receiving constituent services. By ensuring that each representative is subject to requests and suggestions from the same number of constituents, total-population apportionment promotes equitable and effective representation.”

However, Ginsburg stopped short of banning states from counting only eligible voters, which the Obama administration had advocated during oral arguments. In a concurring opinion, Thomas said the Constitution “leaves States significant leeway” to draw districts as they see fit. And Justice Samuel Alito wrote that the court might finally answer the “important and sensitive question” of the constitutionality of drawing districts based on eligible voters when a state drew a map to that effect.

That’s where Trump’s failed push to add a citizenship question, followed by his executive order on citizenship data, comes in. Currently, any state that wants to adopt a citizenship-based map that the Supreme Court might uphold faces a practical problem: States don’t have the street-level citizenship data necessary to draw districts that exclude noncitizens in their population counts. To get this information, the Census Bureau would have to collect citizenship data through the decennial census, which it hasn’t done since 1950. As Hofeller put it in his unpublished study, “Without a question on citizenship being included on the 2020 Decennial Census questionnaire, the use of citizen voting age population is functionally unworkable.” But with this data in hand, a state could test the limits of the Evenwel decision. “If the state of Texas decides it’s going to use citizen population for their state Senate or state House, they’re going to get sued, and we’re going to find out pretty quickly what the Supreme Court thinks about that,” Blum told me. He said his organization, the Project on Fair Representation, would provide legal counsel for any state facing such a lawsuit. He could soon go from suing Texas to supporting it.

One of the flaws—or perhaps it’s a feature—of this plan is that the citizenship data it depends on could be a mess. Even if states like Texas want the data that Trump has promised to release—the Census Bureau said in July that no state has requested it yet—it’s not clear that it will be reliable. During the fight over the citizenship question, the Census Bureau told the administration that using state and federal databases known as administrative records would be more accurate and less obtrusive than asking every person in America their citizenship status. But those records are hardly foolproof.

A leaked Census Bureau document estimates that the agency already has access to citizenship information for 90 percent of people in the country. But more marginalized and transient groups are less likely to show up in official databases, particularly recent immigrants and non-English speakers, as well as people who move a lot, work nontraditional jobs, or possess varying forms of documentation. Redistricting maps are drawn street by street, which means the Census Bureau will need to not only know the citizenship status of everyone in America, but accurately match each person to a current address. That’s a tall order. “I’m real dubious about it,” Beveridge said. “They haven’t done this ever. We’re talking two years from the release, and it hasn’t been tested at all. It’s like the citizenship question 2.0.”

Even if the Census Bureau can produce precise citizenship data, making a clear determination of who is a citizen and who is an eligible voter isn’t easy, especially in a fast-growing state like Texas. At least 50,000 people become naturalized citizens in Texas every year, and about 340,000 kids there turn 18 annually. Someone who is a noncitizen or a nonvoter when census data is collected in 2020 might become eligible to vote in 2021 but still be shut out of political representation for an entire decade.

A recent example from Texas provides a cautionary tale of how bad data, combined with suspect intentions, could disenfranchise many eligible voters. In January 2019, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton tweeted a “voter fraud alert,” claiming that 95,000 noncitizens were registered to vote in the state and 58,000 had voted at least once. Trump shared Paxton’s claim on Twitter and added his own unfounded claim that “voter fraud is rampant.” Acting Secretary of State David Whitley told counties to begin purging suspected noncitizens from voter rolls.

But the list of nearly 100,000 people that Whitley sent out to be purged was riddled with errors. Almost immediately, his office conceded that 25,000 people on the list who were slated to be purged were in fact naturalized citizens. A federal judge blocked the effort, writing that “perfectly legal naturalized Americans were burdened with what the Court finds to be ham-handed and threatening correspondence from the state.” Whitley, a protégé of Gov. Greg Abbott, abandoned the purge and resigned in disgrace after the state legislature refused to confirm him, four months after launching the much-publicized effort.

Nearly every Latino elected official and voting rights expert I talked to in Texas brought up the voter purge to explain why their community feels like Republicans are trying to disenfranchise them. “It was targeted toward removing US naturalized citizens from the voter rolls,” Angelica Razo, the Texas deputy director of the voting rights organization Mi Familia Vota, said. “To me it was saying, ‘You’re not the US citizen that we actually value.’” The aborted voter purge is seen in Texas as a preview of how a redistricting map based on citizenship would unfairly target Latinos. In October, the Census Bureau announced it had been quietly asking states for citizenship data from driver’s license records as part of Trump’s executive order. Two months later, the Department of Homeland Security agreed to share citizenship records with the bureau.

Even without the citizenship data they seek, Trump and Republicans have already set in motion forces that could dramatically weaken the influence of Democrats and communities of color at the ballot box. Though the citizenship question won’t be on the 2020 census, the anxiety it stirred in immigrant communities has not dissipated. “In the minds of our community, it’s still on there,” Razo said. Alvarado agreed: “It’s not going to be a part of the census, but because of the vile political rhetoric that has spewed out of the mouth of Trump and the hatred that he has shown from day one…people are concerned about answering anything. If people come knocking on your door and they want to know how many people are living in your house, that can be seen as a challenge. That can be seen as intrusive. People don’t know what the information is going to be used for.”

If the residents of areas with big immigrant populations like Houston, Dallas, and South and West Texas don’t respond to the census in large numbers, it will open a statistical divide that could shift power to wealthier and whiter areas before the redistricting process has even begun. Unlike California, which has pledged $187 million for census outreach, Texas hasn’t allocated any money, virtually guaranteeing a sizable undercount of Latinos and other communities of color, which are the hardest-to-count groups in the state. While the census is constitutionally required to count every person in America regardless of citizenship status, the 2018 Texas Republican platform called for “an actual count of United States citizens only.” It seems like Texas Republicans—and the Trump administration—want to turn a long-established constitutional mandate into a political weapon. When I asked Alvarado why Republicans would risk losing hundreds of millions in federal funding and one or more additional congressional seats by not ensuring a fair and complete census count, she answered, “Maybe there’s people they don’t want counted.”

Rulings On Gerrymandering And The Census Could Define The Political Future

Mother Jones journalist Ari Berman says recent Supreme Court decisions on redistricting and the 2020 census citizenship question will help determine which party is in power in the next decade.

TERRY GROSS, HOST:

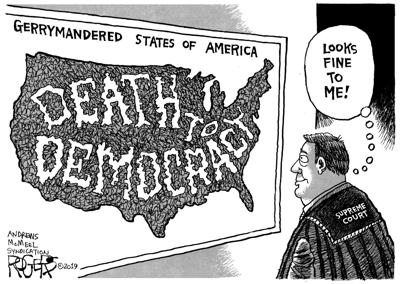

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. The Supreme Court handed down two decisions at the end of their session last month that could have a big impact on the outcome of elections in the States. The court ruled it had no power to intervene when states use partisan gerrymandering to draw maps for electoral districts, saying it was an issue for state legislatures and state courts. And in a related case, the court ruled that the Trump administration could not add a citizenship question to the census.

Though the census questionnaires were scheduled to go to the printer on July 1, President Trump has been tweeting that the government is moving forward with the plan to include the question. Yesterday, Attorney General William Barr said he sees a way for the administration to include the question in the census, that action will be taken within the coming days. The outcome of the census plays a large part in determining electoral districts in the States.

My guest today is Ari Berman, who's been writing about both of these issues, gerrymandering and the census, for Mother Jones magazine, where he covers voting rights. He's also a senior fellow at Type Media and the author of the book "Give Us The Ballot: The Modern Struggle For Voting Rights In America."

Ari Berman, welcome back to FRESH AIR.

ARI BERMAN: Thank you for having me back, Terry.

GROSS: So how is the citizenship question related to political representation?

BERMAN: Well, the census is directly related to political representation, Terry, because the census forms the basis for how we draw political districts. It forms the basis for how many seats a state will get in the House of Representatives. It forms the basis for how many Electoral College votes a state will receive. So the census isn't just one of many surveys; the census really forms the basis for political power in America.

And I think the fear about this citizenship question is that some communities, in particular immigrant communities, are going to be less likely to respond to the census if the citizenship question is on there because they're very afraid of the Trump administration's immigration policies, and they don't want to give the Trump administration their citizenship data. And if immigrant communities don't respond to the census in large numbers, that will shift political power away from areas with lots of immigrants into wider and, quite frankly, more Republican areas.

GROSS: President Trump said we need to know how many citizens there are in order to determine representation. But representation isn't based on citizens; it's based on the number of people.

BERMAN: That's right. And that's a really important point that you made, Terry, and I think it gets at the real reason the Trump administration wants this question about citizenship on the census. Because right now districts are drawn based on total population, so everyone counts when you draw a new political district in the same way that if you have a fire at your house, the fire department isn't going to ask, what's your citizenship status? They're going to put the fire out. And so for decades, districts have been drawn based on total population.

What the Trump administration I think wants to do - they haven't come out and flat out said it, but they've hinted at it - what I think the Trump administration wants to do is draw districts based on citizens, not based on the total population. And they need this question about citizenship on the 2020 census to be able to do that.

But the point of the census is to count every person in America. The constitutional mandate of the census, dating back to 1790, is for a, quote, "just and perfect enumeration" of the population. And if you have certain groups who decline to respond to the census because they're afraid of how their information could be used, that jeopardizes the purpose of the census in the first place, which is to try to count everyone.

GROSS: So what did the Supreme Court rule about the case that the Trump administration was making about the importance of adding the citizenship question?

BERMAN: Well, it was a somewhat convoluted decision, Terry, because when it first came out, I saw tweets saying, Supreme Court upholds citizenship question (laughter), and I saw tweets saying Supreme Court strikes down citizenship question. So I was thinking, well, what actually happened here? And I had to read the opinion two or three times before I really understood it because, for the first 20 pages of the opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts makes the case for why a citizenship question is constitutional.

So you're thinking, OK, he upheld this. Then on Page 23, there's a very abrupt shift, and Roberts says, even though you can do this, you need to have a good reason for it. And the Justice Department's rationale for this and the Trump administration's rationale for this, that this question about citizenship was needed to enforce the Voting Rights Act, in Roberts' words, seems to have been contrived. So what he did is Roberts upheld a lower court decision striking down the citizenship question, and he said to the Trump administration, come up with a better reason, or else this is not going to be on the census.

GROSS: So last week, President Trump ordered the Justice Department to keep pushing forward with the citizenship question. And so the president said there are several routes open - one is an executive order; one is going back to the court. Monday of this week, the Justice Department replaced the legal team that argued the case initially. Where are we now with the citizenship question?

BERMAN: This has been a wild story, Terry (laughter), for a very dry and wonky issue. On Tuesday of last week, the Justice Department and the Commerce Department said that the 2020 census forms would be printed without the citizenship question audit. Voting rights advocates declared victory. It seemed like the question wasn't going to be on the census form. The next day, on Wednesday of last week, President Trump said that he was, quote, "absolutely moving forward" with the question and called reports that they were dropping the question fake, in all caps with an exclamation point.

So that led to a lot of confusion. And lawyers for the Justice Department were completely blindsided by this. One lawyer who was a political appointee in the Trump administration said that they had, quote, "been instructed" to try to find a path forward to adding this question back to the census.

So it seemed like, on Tuesday, they had dropped the question, and then on Wednesday, it was suddenly back on, based on President Trump's tweet. And then subsequently, Trump was tweeting all the time about it and then, on Friday, said that he was considering a number of options, including an executive order. Then on Monday of this week, the news broke that the Justice Department was replacing all of its lawyers on the team handling the citizenship question.

So this is a really (laughter) insane scenario where it seems like President Trump's Twitter feed is determining how the Justice Department is approaching a $10 to $15 billion operation that's constitutionally mandated every 10 years and is one of the most important things we do as a country.

GROSS: What do you think the likely next step would be if the Justice Department continues to pursue this case through the courts?

BERMAN: Well, I think they're going to try to appeal directly to the Supreme Court. They are going to try to come up with what they call a new rationale for adding this question because John Roberts said that their rationale that this was needed to enforce the Voting Rights Act was contrived. So they're going to try to come up with a new rationale. I would imagine that would first go to the lower courts. The lower courts would look at it, unless there is an expedited review, and the Supreme Court basically looks at some briefs and either decides this over the summer or schedules an emergency hearing sometime in the fall.

The problem is we're running out of time here, that the Trump administration repeatedly said to the Supreme Court that census forms needed to be finalized by the end of June. And in fact, that's why they had decided, as of last week, that the forms would be printed without the citizenship question because, over and over and over, they said the deadline for finalizing census forms was the end of June. And that's why the Supreme Court actually heard this case on expedited appeal.

Remember, Terry, this case went directly from the district court to the Supreme Court. It bypassed the court of appeals entirely, which is very, very rare. The reason that happened was because the Trump administration said this was so urgent. So for them to turn around and say, we have a lot more time than we initially told you, would seem to be a mischaracterization to the Supreme Court.

And secondly, they've been arguing for a year and a half that this was needed to better enforce the Voting Rights Act. So the idea that, in a span of a week, they could somehow turn around and say, oh, we have an entirely new reason for this question, but we just didn't present it to the court for over a year, I think that's going to leave some of the justices mystified.

And honestly, Chief Justice John Roberts cares a lot about the legitimacy of the court. He seems to care about the processes by which things are done. And this entire process, from the minute the Supreme Court ruled on the citizenship question, has been such a disaster from beginning to end, with Justice Department reversals, with President Trump's Twitter feed, with the Justice Department replacing all of its lawyers - I can't imagine that's helping their case with John Roberts.

GROSS: So last week, President Trump said he would consider an executive order to add the citizenship question to the census. Wouldn't that be defying the Supreme Court?

BERMAN: First off, does the president even have an authority to do the executive order on the census? My understanding is that Congress has the authority over the census, and they've delegated some responsibility to the Commerce Department, but the President can't change the census via executive order. So I think that alone is unconstitutional. Secondly, I don't think that really solves the Trump administration's problem with the Supreme Court. It wasn't that they didn't have the authority to do this; it was that they didn't have a good reason to do this.

So unless the executive order is accompanied by a very good reason, which had not been presented to the court for over a year, it's hard to see how an executive order solves the Trump administration's problems. To me, it seems more like political posturing than an actual solution to try to get this question back on the 2020 census.

GROSS: There hasn't been a citizenship question on the census since 1950. Why was it on the census before 1950 and why was it taken off after 1950?

BERMAN: It was on before 1950 because it was just one of many pieces of demographic data that the Census Bureau collected. But I think, as the country began to change demographically, as there were more noncitizens, both documented and undocumented, it became more of an invasive question, and they had other means to gather that data.

And after the citizenship question was dropped in the 1950s, every time there was some discussion about adding it back, the Census Bureau opposed it, and they said this question is going to provoke a lot of fear. It's going to make the census less accurate because people are going to lie about their citizenship status out of fear. And we have other means of collecting this data that's less intrusive.

GROSS: Let me reintroduce you here. If you're just joining us, my guest is Ari Berman. He's a senior reporter at Mother Jones magazine, covering voting rights. He's the author of "Give Us The Ballot: The Modern Struggle For Voting Rights In America." And he's a fellow at Type Media. We're going to talk more about voting issues, including the Supreme Court decision that was handed down last month about gerrymandering. We'll be right back. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF SLOWBERN'S "WHEN WAR WAS KING")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. And if you're just joining us, we're talking about voting issues and the two big Supreme Court decisions. My guest is Ari Berman. He's the author of the book "Give Us The Ballot: The Modern Struggle For Voting Rights In America." And he covers voting rights for Mother Jones, where he's a senior reporter.

So, you know, there's a person who is a big connection between the gerrymandering issue, which the Supreme Court just handed a ruling on, and the citizenship question, which the Supreme Court just handed down a ruling on, and that person is Thomas Hofeller. You describe him as the GOP's longtime redistricting mastermind. So after his death, his estranged daughter Stephanie found his hard drives, which she thought might have important information on it. So she turned it over to the North Carolina branch of Common Cause, which was challenging partisan gerrymandering.

What are some of the things that we learned from these hard drives about his motivations for partisan gerrymandering and adding the citizenship question to the census?

BERMAN: This was a crazy turn of events. So there was a lawsuit in North Carolina challenging the state legislative maps in North Carolina in state court. And they got all of these files from Thomas Hofeller, who, for decades, until he passed away last year, has been the lead expert on redistricting for the Republican Party. He was the redistricting counsel for the Republican National Committee. He drew maps for Republicans in virtually every important swing state dating back decades.

And what these files showed was that Hofeller had authored a study in 2015 that analyzed the impact of adding a citizenship question on the 2020 census. And what the study showed was that Hofeller said that this would be clearly disadvantageous to Democrats and an advantage to Republicans and non-Hispanic whites. And if you wanted to draw districts based on citizenship rather than total population, you needed a citizenship question on the census to do this, which Hofeller said would be a radical departure from the one person, one vote standard the Supreme Court issued in the 1960s.

So this was giant, smoking gun evidence. Here you had the Republican Party's lead redistricting expert, the guy who drew gerrymandered maps in states all across the country, saying that the purpose of the citizenship question was to try to draw districts to help Republicans and whites. Now, a lot of us believe that was the purpose of the question all along, but to have someone of Hofeller's stature say this was really eye-opening.

GROSS: I'm not sure you'd know the answer to this, but I've been trying to understand why this issue is so important to President Trump. Now, I know immigration and people who are here without documentation is one of his key issues, so there's that, but he must also know that it figures into voting issues. So do you think that Trump is behaving kind of unilaterally? Do you think that there are people within the party - do you think there are people who are pressuring him to keep moving forward on this?

BERMAN: Absolutely. We know, for example, that people like Kris Kobach, the former secretary of state of Kansas who has been one of the leading architects in the Republican Party of cracking down on immigration and also of restricting voting rights, began discussing the citizenship question all the way back in 2016 with the Trump campaign. And then Kobach said he brought this up with President Trump after the inauguration. He discussed it with President Trump. He discussed it with Steve Bannon. He discussed it with then-White House chief of staff Reince Priebus.

And it was Bannon who called Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, who oversees the Census Bureau, and said, you need to talk to Kobach about the citizenship question. And Kobach said in July of 2017 that it was essential that Wilbur Ross add this question to the census because Kobach - in Kobach's words, Kobach wanted to draw districts in such a way that only citizens were counted. So, clearly, you had a political motivation there - that - one of the reasons, I think, major figures in the conservative movement are pushing for this question is so that they can try to draw districts in a way that's advantageous to the Republican Party and advantageous to the preservation of white political power.

You also have some figures in the Trump administration that want the citizenship question so they can use it for immigration enforcement purposes. Now, it's not clear how they're going to actually do this because the question - the Census Bureau is not going to ask people whether they are undocumented or documented. They're just going to ask people, are you a citizen or not? So they're not going to get information on how many undocumented people there are to initiate deportation raids, for example. They're not going to get that information from the citizenship question. Not only that, but census information is confidential. And this is really, really important because during World War II, the Census Bureau shared information on Japanese Americans with the Secret Service, which was then used to intern Japanese Americans during World War II - a very, very dark period in our country's history and a very, very dark period for the Census Bureau. And they have adopted very strict confidentiality standards. They're not allowed to share data with the Department of Homeland Security or other agencies.

So I don't know what they're planning to do with immigration enforcement, but I don't even think they're going to be able to achieve their agenda based on this question. But absolutely, politically, if they're able to get this citizenship question on the 2020 census, it would make it a lot easier for them to be able to escalate the gerrymandering they're already doing in the post-2020 redistricting cycle by drawing districts based on citizenship rather than total population.

GROSS: So just to be clear, if citizenship is used to determine political representation, that means that people who are living here legally, people who have green cards, people who are working and paying taxes, would have no representation, and the places where they live wouldn't get federal funds that count them as living there because certain federal funds are apportioned to states according to how many people are there. They wouldn't be counted.

BERMAN: That's correct. It could have a very significant impact because I think what people are thinking of is that only undocumented people will be excluded from counting. And by the way, already districts are drawn in such a way that counts everyone. So you can have that argument about whether or not they should be counted. But as of now, everyone is counted. But it wouldn't just be people that are undocumented. It would be people that are here legally that are noncitizens. And then a lot of people who are citizens would be hurt by this just by virtue of the fact that they live in the same kind of areas.

And so you would have places like Los Angeles and New York City and Chicago and Houston and Dallas, all of these big metro areas - all of which tend to lean heavily Democratic - they are going to get less money. They're going to have less political power. They're going to have less representation. So it's going to be a shift from blue areas to red areas.

And then even within states like Texas that are more conservative, it's going to shift power from Democratic areas to redder areas. And so I think this is really the Republican Party's long-term plan for trying to preserve white political power. They believe by adding this citizenship question on the census that they can both depress response rates from immigrant communities so that those places have less power.

But on a broader sense, they want to be able to draw districts for the next decade and beyond that enshrine white political power. And the citizenship question on the census is their best vehicle for doing so. And I think that's the reason you're seeing President Trump push so hard for this question even after the Supreme Court largely shut the door.

GROSS: My guest is Ari Berman. He covers voting rights for Mother Jones magazine. After a break, we'll talk about the Supreme Court's decision on gerrymandering and how it may affect the outcome of state elections and the future makeup of the House of Representatives. And Maureen Corrigan will review a new novel she describes as a story about racism, class and the limits of individual possibility. I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF JOEL FORRESTER AND PEOPLE LIKE US' "THE COP-OUT")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. Let's get back to my interview with Ari Berman, who covers voting rights for Mother Jones magazine and is the author of the book "Give Us The Ballot: The Modern Struggle For Voting Rights In America."

Last week, the Supreme Court handed down two decisions that will have an impact on voting and the outcome of elections. The court ruled that the Trump administration could not add a citizenship question to the census, at least not based on the rationale the administration presented. But the administration is still pursuing adding the question. The other decision was about gerrymandering.

Let's get to gerrymandering and last month's Supreme Court decision. I'm going to ask you to explain the decision and explain why you describe that decision as a doomsday scenario for voting rights.

BERMAN: What the Supreme Court said in a 5-4 decision on two gerrymandering cases was that partisan gerrymandering could not be reviewed by the federal courts. And this was a huge setback for voting rights, as I said a doomsday scenario for voting rights because the problem of partisan gerrymandering is getting worse and worse. The maps drawn after the 2010 election during the last redistricting cycle were so much more extreme than the maps drawn during the previous decade. You had a situation, for example, in places like Wisconsin, where Republicans for the state assembly got 46% of votes in 2018 but 64% of legislative seats. That is so unbelievably undemocratic. It goes against everything we believe in a democracy, which is that the person who gets the most votes should be the person who's holding office.

But over and over again, we're seeing that Republicans, in particular, because they control the drawing of so many more seats after the 2010 redistricting cycle, they are getting a minority of votes but a majority of seats in key swing states. And so the problem of gerrymandering is getting worse. Lower federal courts are recognizing this. You had decisions by lower courts, lower federal courts in states like Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio and North Carolina that struck down gerrymandered maps.

So gerrymandering is getting worse. The federal courts are recognizing this problem, but the Supreme Court said, not only can we not solve this problem, we can't even review it. And that is just going to incentivize the worst self-interested political behavior in both parties going into the next redistricting cycle, which begins in 2021.

GROSS: What was the Supreme Court's rationale for saying, we can't intervene in a state's decision on partisan gerrymandering?

BERMAN: The decision was written by Chief Justice John Roberts. And what Roberts said was that redistricting is an inherently political process. And he went back to the Founding Fathers. And he basically said they recognized the dangers of gerrymandering. He gave the example where Patrick Henry tried to gerrymander James Madison in Virginia in the late 1700s. And he basically said, they recognized the problem of gerrymandering, but they left it to state legislatures to deal with. So this was an issue for the states not for the courts.

And there was this fascinating back and forth between John Roberts and Elena Kagan, who wrote a very, very strong dissent in the case. And they were arguing not just about the present day but about history. And Roberts was saying the Founding Fathers were basically OK with gerrymandering or they believed the states should solve it. And Kagan was saying that the chief concern of the Founding Fathers was that the people should be able to rule and that nothing undermines the ability of people to rule more than gerrymandering, where election outcomes are predetermined by who controls the drawing of the maps.

And Kagan said in its most extreme form, gerrymandering amounts to election rigging. And she said, don't just look at history. Look at the present day; that the gerrymandering of now is so much more extreme than it had been in the past. And we are basically saying we know this problem is going to get worse, but we can't do anything about it. And that is a total abdication of the responsibility not just of the federal courts but of the highest court in the land.

GROSS: So, basically, whichever party is in power in the state House gets to draw the districting boundaries every 10 years. And the cycle starts again in 2021, which is very soon. So...

BERMAN: Exactly.

GROSS: There's a lot at stake here. And it will be determined - what - it will determine the next 10 years politically.

BERMAN: Exactly. And that's one reason why the Supreme Court case was so significant not just for what they ruled - that partisan gerrymandering can't be reviewed by the federal courts - but also the timing; the fact that we know the next redistricting cycle is going to happen in 2021. And what happened after the 2010 election was that was a wave election by Republicans. That was the Tea Party wave election. And they were able to take over virtually every important swing state in the country. And they were able to draw state legislative and U.S. House districts in four times as many places as Democrats, so Republicans had a huge advantage in the last redistricting cycle.

And if you look at the numbers, Republicans still control every state legislative chamber in key swing states like Wisconsin and Michigan and North Carolina and Ohio and Pennsylvania. And that's not because they're so popular in those states. It's because they controlled the drawing of the maps in 2011 and were able to lock in Republican political power for the next decade. And that could become even easier to do now in 2021, knowing that there is going to be no federal review of this process. If they just do a partisan gerrymander, if they don't do a racial gerrymander or other things like that, which are still unconstitutional, but if they just draw districts to try to benefit one party or the other, the Supreme Court has said, we're not going to stop that.

GROSS: Republicans actually had a strategy for taking over majority control of the states, in part, to be able to control redistricting.

BERMAN: They did. And they were very open about this. In March of 2010, Karl Rove published a op-ed in The Wall Street Journal. And he says, he who controls redistricting will control Congress, so he said it. And they formed a group. It was called REDMAP, which is the Republican redistricting strategy. And they raised a lot of money. This was after the Citizens United decision, in which the Supreme Court said you could raise unlimited money from corporate entities and from large donors. And so they raised a lot of money from big donors from corporate interests.

They put that money - which was $30 million, which was a lot of money to spend on state races. They put that money in obscure state legislative races that nobody was focusing on in 2010. They were able to flip virtually every important key swing state - places like Wisconsin and North Carolina and Ohio and Michigan. And then after they got these legislative majorities, they were - they then connected their redistricting experts with the state legislatures that were just elected.

So they had a plan all the way through. They had a plan to raise the money needed to take back state legislatures. They had a plan to elect new state legislatures. And then they had a plan for these state legislatures to gerrymander as effectively as possible to retain power for the next decade. And the plan worked absolutely beautifully from beginning to end, and Democrats had no comparable strategy at any point in this process.

GROSS: So now there's a group of Democrats trying to regain majorities in states so that they have some control over districting in 2021. And Obama's first attorney general, Eric Holder, has made ending partisan gerrymandering his issue. And you say, while everybody's focusing on 2020 and the presidential election, Eric Holder and his group are focusing on 2021 and on redistricting. So what is his goal?

BERMAN: His goal, which I write about in the new issue of Mother Jones, is to try to unrig what he views as a rigged political system where Republicans have unified control - so both the governor's office and both branches of the state legislature and key states like Wisconsin. And he is fighting a multipronged battle. His group, the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, they are filing lawsuits against gerrymandering. They are trying to advocate for things like independent redistricting commissions to make the process more fair and less political, less partisan to one party or another.

I think the main thing that Eric Holder is trying to do is to get more attention on state legislative races because during the Obama era, Democrats lost nearly 1,000 state legislative seats. It's absolutely remarkable just how much state power cratered for Democrats. And they're trying to rebuild this. Democrats did a fairly good job in 2018. They picked up nearly 300 state legislative seats. They were able to elect Democratic governors in some places like Wisconsin to break up one-party rule.

But there's still a long way for them to go, and Holder is very concerned that with 20-something people running for president on the Democratic side that state legislative elections are being overlooked and that people are spending so much time focusing on the presidential election, they're forgetting that these state legislative elections in 2020 are going to determine power at both the congressional level and the state legislative level for the next decade. And so Holder is frantically trying to catch up.

GROSS: Is Holder's goal to get Democrats to draw the district maps instead of Republicans, or is his goal to make that process truly nonpartisan?

BERMAN: He says his goal is to try to make the process more nonpartisan and more apolitical than it currently is. He told me, I don't want to replace a Republican gerrymander with a Democratic gerrymander. And so he's supported things like independent redistricting commissions. Their main goal has been trying to break up one-party rule in places like Wisconsin so that the map will be a product of compromise. That is really where he's focused the majority of his attention. But there is a tension within the Democratic Party about this.

And that tension is only going to be exacerbated by the Supreme Court's decision. You're going to have officials in the Democratic Party say, why should I unilaterally disarm if the Supreme Court gave a green light to partisan gerrymandering and the Republicans are going to do it everywhere, but in Democratic states, we're just going to pass fair maps that have more balanced representation? Well, that's going to put us at a severe disadvantage.

GROSS: Let's take a short break here, and then we'll talk some more. If you're just joining us, my guest is Ari Berman. He reports on voting rights for Mother Jones magazine, where he's a senior reporter, and he's the author of the book "Give Us The Ballot: The Modern Struggle For Voting Rights In America." We'll be right back. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. And if you're just joining us, my guest is Ari Berman. He's the author of the book "Give Us The Ballot: The Modern Struggle For Voting Rights In America," and he reports on voting rights for Mother Jones magazine.

Last year, voters in five states approved ballot initiatives to turn over redistricting to independent commissions. So how do some of those commissions look as an alternative to partisan gerrymandering?

BERMAN: It depends on the state, and it depends on the process. But I think, generally speaking, these commissions produce maps that on the whole are thought to be fair and more representative of the state as a whole. And it works in different ways. In a place like Iowa, for example, they have a nonpartisan demographer who is very well-respected. And that person just draws the districts with minimal interference from the legislative process. In other places, like in Michigan in 2021, they're going to have a citizens' commission. So they're going to have people with different ideologies, but they're going to be people that are not part of the legislature and not part of the political process.

Now, the thing you always worry about with these commissions is, are the politicians in power going to try to undermine them? 'Cause already we saw in one state, in Missouri, that passed an independent redistricting commission where a nonpartisan group is going to draw the districts there. We already saw legislation proposed in the legislature in the last term to try to weaken that commission. Now, it didn't pass, but it could easily pass again in 2020. So ballot initiatives are not a cure-all, and independent commissions are not a cure-all.

And one of the things I think people were disturbed about in John Roberts' decision and the gerrymandering case is he pointed to independent redistricting commissions as one solution to this problem. But Roberts didn't note that in 2015, he voted to gut an independent redistricting commission from the state of Arizona.

So I think some cynical people believe the Supreme Court's saying, OK, you can use independent redistricting but then those commissions are going to come before the Supreme Court, and the Supreme Court's then going to strike those very commissions down. Now, that would be incredibly hypocritical for the court to do that, but nonetheless, four justices are already on record as supporting that position. It was only Anthony Kennedy, who's no longer on the court, that saved the viability of independent redistricting commissions in places like Arizona.

GROSS: There's another big voting issue that you've been following, and this pertains to Florida. Last year, Florida voters approved a ballot initiative overturning the state's law saying that convicted felons could never vote again. And so overturning that would have restored the vote to 1.4 million Floridians, but the Republicans countered that. What did they do?

BERMAN: What Republicans in the Florida legislature did is they passed a law this year, which was just signed by the governor, was to require all of those people with past felony convictions that were set to get their voting rights restored, that they would have to pay all fines, fees and restitution before becoming eligible to vote. Now, this is such a big deal because so many people with past felony convictions in Florida owe tens of thousands of dollars in fines, fees or restitution after their sentence. And I think the voters in Florida, broadly speaking, when they passed this initiative restoring voting rights to ex-felons in 2018, I think they believed that if you had paid your debt to society, you would be able to vote and that paying your debt meant serving your time.

That was - when I reported in Florida, that's how I understood how the public viewed this issue. But it's very, very easy to find people who owe tens of thousands of dollars in fines and fees and restitution and many of them are poor, and they'll never be able to pay this off.

And so what the ACLU and other groups who are challenging this new law are saying is that this is a poll tax, that this essentially conditions voting on how much money you have and whether you can pay your fines and fees off. And there was a study that was done about a decade ago that said that up to 40% of those people who are waiting to have their rights restored owed past fines and fees. If you look at the 1.4 million people that were set to have their rights restored, if 40% of them can't pay off their fines, that means over half a million people who are set to have their right to vote back might not actually get the right to vote back. That's an enormous number of people who could potentially be disenfranchised by this new law.

GROSS: And it's also an enormous number of people who could tip the balance for the state in the next presidential election.

BERMAN: Absolutely. You just look at the 2018 election in Florida. The Senate race in Florida was decided by 10,000 votes. The governor's race in Florida was decided by 30,000 votes. In that same election, 1.7 million people couldn't vote because of a past felony conviction. And 1.4 million of those people were set to have their voting rights restored. So that meant there could be over a million new voters eligible to cast a ballot in one of the most important swing states of the country. And this disproportionately affects African American voters who make up more than 20% of those people that have lost their voting rights. They also made up a huge chunk of people who registered to vote after the ballot initiative went into effect before the Florida legislature passed this new law.

So I think the feeling is that this is going to shrink the number of voters. And in particular, it's going to hurt black voters and Democratic-leaning voters - not exclusively. There's going to be a whole lot of white Republican ex-felons who are going to lose their voting rights as well, but because of mass incarceration and because of the way our criminal justice system works, felon disenfranchisement falls more on some people, particularly minority communities, than others. And now you're just putting an entirely new roadblock up for them. And so I think there are going to be some people that won't be able to pay their fines off at all.

There are going to be other people that actually probably are eligible to vote, but they're not going to be sure about the process, and they're not going to want to take the risk of possibly voting for fear that they could be prosecuted if they had made some sort of mistake. And so I think this just sends a real chilling message in Florida to a group that's already pretty vulnerable and marginalized, thought they were in line to get their rights back and now they might not or it might be that they have to complete step X, Y and Z instead.

GROSS: Ari Berman, thank you so much for talking with us.

BERMAN: Thank you so much for having me back, Terry.

GROSS: Ari Berman covers voting rights for Mother Jones magazine and is the author of the book "Give Us The Ballot: The Modern Struggle For Voting Rights In America." After we take a short break, Maureen Corrigan will review a new novel partly inspired by the author's family's encounter with violent racial hatred. This is FRESH AIR.

Copyright © 2019 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

No comments:

Post a Comment