NORTON META TAG

27 March 2010

U.S., Russia agree to nuclear arms control treaty 26MAR10

Swords to plowshares every chance we get!

By Mary Beth Sheridan and Michael D. Shear

Washington Post Staff Writers

Saturday, March 27, 2010; A02

President Obama announced a major new U.S.-Russia nuclear arms treaty Friday, gaining a critical victory as U.S. diplomats head into an intense period of international meetings aimed at keeping the devastating weapons out of the hands of rogue states and terrorists.

Just days after the new pact is signed April 8, Obama will host perhaps the biggest summit ever in Washington, to urge countries to lock down loose nuclear material. A few weeks later, the U.S. government will try to strengthen the world's bedrock agreement limiting the spread of nuclear weapons.

But if the president has gained momentum on pushing his nuclear agenda globally, he still may face a fight getting the 10-year Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or START, through the Senate this year. The deal with Russia will need Republican backing to get the 67 votes required for ratification.

Arms-control experts said the main virtue of the new pact was that it would allow the two countries that own nearly 95 percent of the world's nuclear weapons to continue verifying each other's stockpiles. But as details emerged Friday, it appeared the new treaty might make lower-than-advertised changes in each country's arsenals. While U.S. officials touted a 30 percent lowering of the ceiling for warheads and bombs deployed for long-range missiles, arms-control experts warned that the new pact used different counting rules than previous ones.

The new limit of 1,550 deployed warheads could represent an actual decline of only about 100 or 200 weapons -- a reduction of only as much as 13 percent -- from the comparable figure under the previous treaty, said Hans M. Kristensen, director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists.

A White House official, who like others spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal deliberations, cautioned that the exact reductions had not been determined.

Each side will also reduce to 700 the number of deployed missiles and bombers that can launch nuclear weapons. That represents a reduction of about 100 to 200 from current U.S. levels, according to estimates by experts.

Sen. John F. Kerry (D-Mass.) acknowledged Friday that Senate consideration will take place in a strained legislative environment but pleaded with his colleagues to set their broader political agendas aside.

"I know there has been a partisan breakdown in recent years, but we can renew the Senate's bipartisan tradition on arms control and approve ratification of this treaty in 2010," said Kerry, who heads the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. The committee's top Republican, Sen. Richard G. Lugar (Ind.), a prominent moderate, called for quick ratification.

Several Republicans who have expressed concern about the treaty said they would wait to see it before issuing judgment. One senior Republican source, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said the key to approving the agreement would be the strength of its verification procedures.

Negotiations on START had bogged down in recent months, raising fears among arms-control activists that the president would be dealt a setback as U.S. diplomats went into critical global meetings on nonproliferation.

Negotiators said they ran into impasses over Russia's demands for less intrusive verification rules and its unwillingness to share the same amount of telemetry data on its missile tests, according to people familiar with the talks. In addition, the two sides clashed over U.S. plans for a missile defense shield in Europe. Washington says that system is aimed at Iran, but the Russians view it as a threat on their borders.

A phone call between Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev on Dec. 4, the day before the old treaty expired, failed to produce momentum toward an agreement that U.S. officials had hinted might be coming.

"There were some concerns among the Russian Defense Ministry that things might not have been going the way they wanted," said one person familiar with the December discussions. "Medvedev heard the concerns of his top defense folks and realized more work needed to be done."

On the American side, negotiators were aware that any significant limits on verification or the U.S. missile shield would be unacceptable to Senate Republicans and the Pentagon. The U.S. side appears to have largely won the battle over missile defense, with a mention of it in the treaty's preamble but no new limits imposed on the American system, officials said.

American officials said Obama and Medvedev talked 10 times on the phone and five times in person throughout the past year, often at times when the negotiations in Geneva had bogged down.

The White House official said the turning point came in a testy conversation between Obama and Medvedev in late February.

"The Russians were pushing for constraints on missile defense to be incorporated into the treaty. The president said that was simply unacceptable," the official said.

Obama indicated he was willing to walk away from the treaty, the official said. "That was the breaking point."

The Russians backed off, and Obama dispatched Ellen Tauscher, the undersecretary of state for arms control, to Geneva with longtime State Department arms-control expert James Timbie. Tauscher helped spark the final push toward agreement.

"It was like a light switch," one senior administration official said.

Tauscher, a former Wall Street investment banker, said in an interview: "The test for me isn't the deal you're doing. It's whether you want to do another deal. And we have people who want to do another deal -- on both sides."

However, analysts say any new negotiations seeking deeper cuts will probably be far more difficult, with disputes over such thorny issues as missile defense, Russia's advantage in short-range nuclear weapons, and the superiority of U.S. conventional forces.

As a result, said Pavel Podvig, a scholar at the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University, the new treaty signed in April could be the last to emerge from Cold War-style negotiations, with each side seeking to balance its forces against the other's.

Alexander Konovalov, president of the Moscow-based Institute for Strategic Assessments, said any further nuclear cuts would face resistance in the Russian military, which believes Moscow needs a strong nuclear arsenal to compensate for the weakness of its conventional forces.

"It's simply fear," he said. "The military world is very conservative, and it is difficult to change their way of thinking."

Staff writer Karen DeYoung in Washington and correspondent Philip P. Pan in Moscow contributed to this report.

By Mary Beth Sheridan and Michael D. Shear

Washington Post Staff Writers

Saturday, March 27, 2010; A02

President Obama announced a major new U.S.-Russia nuclear arms treaty Friday, gaining a critical victory as U.S. diplomats head into an intense period of international meetings aimed at keeping the devastating weapons out of the hands of rogue states and terrorists.

Just days after the new pact is signed April 8, Obama will host perhaps the biggest summit ever in Washington, to urge countries to lock down loose nuclear material. A few weeks later, the U.S. government will try to strengthen the world's bedrock agreement limiting the spread of nuclear weapons.

But if the president has gained momentum on pushing his nuclear agenda globally, he still may face a fight getting the 10-year Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or START, through the Senate this year. The deal with Russia will need Republican backing to get the 67 votes required for ratification.

Arms-control experts said the main virtue of the new pact was that it would allow the two countries that own nearly 95 percent of the world's nuclear weapons to continue verifying each other's stockpiles. But as details emerged Friday, it appeared the new treaty might make lower-than-advertised changes in each country's arsenals. While U.S. officials touted a 30 percent lowering of the ceiling for warheads and bombs deployed for long-range missiles, arms-control experts warned that the new pact used different counting rules than previous ones.

The new limit of 1,550 deployed warheads could represent an actual decline of only about 100 or 200 weapons -- a reduction of only as much as 13 percent -- from the comparable figure under the previous treaty, said Hans M. Kristensen, director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists.

A White House official, who like others spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss internal deliberations, cautioned that the exact reductions had not been determined.

Each side will also reduce to 700 the number of deployed missiles and bombers that can launch nuclear weapons. That represents a reduction of about 100 to 200 from current U.S. levels, according to estimates by experts.

Sen. John F. Kerry (D-Mass.) acknowledged Friday that Senate consideration will take place in a strained legislative environment but pleaded with his colleagues to set their broader political agendas aside.

"I know there has been a partisan breakdown in recent years, but we can renew the Senate's bipartisan tradition on arms control and approve ratification of this treaty in 2010," said Kerry, who heads the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. The committee's top Republican, Sen. Richard G. Lugar (Ind.), a prominent moderate, called for quick ratification.

Several Republicans who have expressed concern about the treaty said they would wait to see it before issuing judgment. One senior Republican source, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said the key to approving the agreement would be the strength of its verification procedures.

Negotiations on START had bogged down in recent months, raising fears among arms-control activists that the president would be dealt a setback as U.S. diplomats went into critical global meetings on nonproliferation.

Negotiators said they ran into impasses over Russia's demands for less intrusive verification rules and its unwillingness to share the same amount of telemetry data on its missile tests, according to people familiar with the talks. In addition, the two sides clashed over U.S. plans for a missile defense shield in Europe. Washington says that system is aimed at Iran, but the Russians view it as a threat on their borders.

A phone call between Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev on Dec. 4, the day before the old treaty expired, failed to produce momentum toward an agreement that U.S. officials had hinted might be coming.

"There were some concerns among the Russian Defense Ministry that things might not have been going the way they wanted," said one person familiar with the December discussions. "Medvedev heard the concerns of his top defense folks and realized more work needed to be done."

On the American side, negotiators were aware that any significant limits on verification or the U.S. missile shield would be unacceptable to Senate Republicans and the Pentagon. The U.S. side appears to have largely won the battle over missile defense, with a mention of it in the treaty's preamble but no new limits imposed on the American system, officials said.

American officials said Obama and Medvedev talked 10 times on the phone and five times in person throughout the past year, often at times when the negotiations in Geneva had bogged down.

The White House official said the turning point came in a testy conversation between Obama and Medvedev in late February.

"The Russians were pushing for constraints on missile defense to be incorporated into the treaty. The president said that was simply unacceptable," the official said.

Obama indicated he was willing to walk away from the treaty, the official said. "That was the breaking point."

The Russians backed off, and Obama dispatched Ellen Tauscher, the undersecretary of state for arms control, to Geneva with longtime State Department arms-control expert James Timbie. Tauscher helped spark the final push toward agreement.

"It was like a light switch," one senior administration official said.

Tauscher, a former Wall Street investment banker, said in an interview: "The test for me isn't the deal you're doing. It's whether you want to do another deal. And we have people who want to do another deal -- on both sides."

However, analysts say any new negotiations seeking deeper cuts will probably be far more difficult, with disputes over such thorny issues as missile defense, Russia's advantage in short-range nuclear weapons, and the superiority of U.S. conventional forces.

As a result, said Pavel Podvig, a scholar at the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University, the new treaty signed in April could be the last to emerge from Cold War-style negotiations, with each side seeking to balance its forces against the other's.

Alexander Konovalov, president of the Moscow-based Institute for Strategic Assessments, said any further nuclear cuts would face resistance in the Russian military, which believes Moscow needs a strong nuclear arsenal to compensate for the weakness of its conventional forces.

"It's simply fear," he said. "The military world is very conservative, and it is difficult to change their way of thinking."

Staff writer Karen DeYoung in Washington and correspondent Philip P. Pan in Moscow contributed to this report.

Labels:

Medvedev,

nuclear arms control,

Obama,

pentagon,

Russia,

senate,

START treaty,

U.S.A.

H.R. 4789 THE MEDICARE YOU CAN BUY INTO ACT

Congress failed to pass a public option. Now, Rep. Alan Grayson is leading the charge to set things right -- with his "Medicare You Can Buy Into Act." It's a 3-and-a-half page bill, it's a stronger public option, and it's got momentum...80 co-sponsors in its first week. Watch the video and then click on the header to participate.

Labels:

congress,

healthcare,

house,

Medicare,

public option,

Rep. Alan Grayson

26 March 2010

TEACH THE CHILDREN WELL

Only when enough adults practice and teach children love and respect at home, in schools, religious congregations, and in our political and civic life will racial, gender, and religious intolerance and hate crimes subside in America and the world.

- Marian Wright Edelman, from her book Lanterns

Goodness is a process of becoming, not of being. What we do over and over again is what we become in the end.

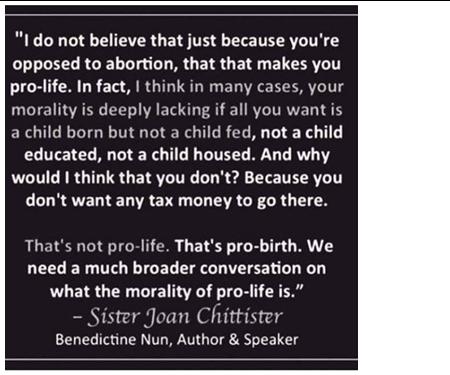

- Joan Chittister,

Benedictine nun, author, and lecturer.

- Marian Wright Edelman, from her book Lanterns

Goodness is a process of becoming, not of being. What we do over and over again is what we become in the end.

- Joan Chittister,

Benedictine nun, author, and lecturer.

GLEANING

You shall not strip your vineyard bare, or gather the fallen grapes of your vineyard; you shall leave them for the poor and the alien.

- Leviticus 19:10

- Leviticus 19:10

Labels:

Christian Socialism,

Christianity,

gleaning,

Matthew 25

OUR LIVES

If our lives demonstrate that we are peaceful, humble and trusted, this is recognized by others. If our lives demonstrate something else, that will be noticed too.

- Rosa Parks, civil rights activist (1913-2005)

- Rosa Parks, civil rights activist (1913-2005)

MY AUNT LYNN WAS KILLED IN A CAR ACCIDENT SUNDAY EVENING part 2 14MAR10

I went to Pennsville, NJ last Friday with my sister Jennie and her daughter Katie for our Aunt Lynn's funeral. We met Mom and Dad and Uncle Ralph and Aunt Pat at the hotel. Lynn was Mom's and Ralph's sister. It was a beautiful day, Spring making a welcome appearance, and I know Aunt Lynn loved that because she loved Spring and being in the county with all the trees and flowers and wildlife. We, the family, had a chance to see Aunt Lynn before the funeral, it was good to be able to see her here one last time, though it was, and is still hard to believe it was her funeral. A lot of people came to pay their respects to Aunt Lynn and her family. And it was good to be with family, good to see cousins I haven't seen for too long, though I wish it had been for another reason. The preacher had a very good message and was a great comfort to us. Aunt Lynn's wish is that she be cremated, and some of her ashes be scattered around Uncle Bill's grave and the rest be scattered along her favorite trail on Skyline Drive. She went there at least twice a year to commune with nature and refresh her soul. We will join her kids when they make the journey, probably on Mother's Day.

The young man that caused the accident that killed Aunt Lynn is in his early twenties. He was talking on his phone while driving. I believe he is being charged with vehicular homicide. I feel sorry for him too, he will have to live the rest of his life knowing his carelessness killed another person. He may have to spend some time in prison. I hope and pray he has faith and family to help him deal with this.

I am guilty of talking on my phone while driving but no more. Period. I will not answer my phone while driving and if I call someone's cell phone and they are driving I will end the call and they can call me back or I will call them back when they get to their destination. I will not risk putting another family through this.

So many friends have been so supportive of me and my family through this, I can only say thank you from the bottom of my heart and that I love you all so very much.

The young man that caused the accident that killed Aunt Lynn is in his early twenties. He was talking on his phone while driving. I believe he is being charged with vehicular homicide. I feel sorry for him too, he will have to live the rest of his life knowing his carelessness killed another person. He may have to spend some time in prison. I hope and pray he has faith and family to help him deal with this.

I am guilty of talking on my phone while driving but no more. Period. I will not answer my phone while driving and if I call someone's cell phone and they are driving I will end the call and they can call me back or I will call them back when they get to their destination. I will not risk putting another family through this.

So many friends have been so supportive of me and my family through this, I can only say thank you from the bottom of my heart and that I love you all so very much.

Labels:

Aunt Lynn,

cell phones,

Christianity,

death,

driving,

faith,

family

Healthcare and the Supreme Court from MOJO 23MAR10

An interesting article, check out the piece by Ezra Klein from the American Prospect after the story from Mother Jones. He suggest instead of fining people for not having insurance they should be able to opt out of the HRC mandates, but they have to stay out for five years, so if catastrophic illness would hit in that five year period they would have to live, or die, with their decision. Click the header for the story from MOJO.

By Kevin Drum

| Tue Mar. 23, 2010 8:39 AM PDT

A reader writes:

Of all the potential legal challenges to HCR out there, Ken Cuccinelli's planned lawsuit seems to me to potentially be the most viable. Assuming this issue gets to the U.S. Supreme Court, I wouldn't be a bit surprised if the (Republican majority) Roberts Court agreed with Cuccinelli. If that happens, what, exactly, is the Democrats' back-up plan?

I'm not sure what the best response to this is. Cuccinelli's suit argues that the individual mandate in the healthcare bill is unconstitutional: “We contend that if a person decides not to buy health insurance, that person — by definition — is not engaging in commerce, and therefore, is not subject to a federal mandate.” The argument here is that if it's not commerce, then it's not interstate commerce. And if it's not interstate commerce, then Congress has no constitutional authority to regulate it.

I'm not a lawyer, but this seems like the ultimate Hail Mary to me. There's longstanding precedent — hated by conservatives, but only slightly rolled back even by the Rehnquist court — that the interstate commerce clause gives Congress extremely wide power to regulate activity that affects interstate commerce in almost any way, and there's simply no question that the individual mandate is inextricably tied up with interstate commerce. The insurance industry and the medical industry are practically textbook definitions of interstate enterprises, and allowing healthy people to opt out of healthcare coverage has a very direct effect on that business. Frankly, even for an activist conservative court, this seems like a pretty open-and-shut case.

What's more, the penalties for not buying insurance are tax penalties, and if anything, Congress has even wider scope in the tax area than in the commerce area. The Supreme Court has frequently ruled that Congress can pass tax laws that essentially force people to do things that Congress doesn't have the direct power to require.

Bottom line, then: I'm not sure Democrats need a Plan B. But here's the thing: if the Supreme Court decided to overturn decades of precedent and strike down the mandate even though Kevin Drum says they shouldn't (hard to imagine, I know), the insurance industry will go ballistic. If they're required to cover all comers, even those with expensive pre-existing conditions, then they have to have a mandate in order to get all the healthy people into the insurance pool too. So they would argue very persuasively that unless Congress figures out a fix, they'll drive private insurers out of business in short order. And that, in turn, will almost certainly be enough incentive for both Democrats and Republicans to find a way to enforce a mandate by other means. If necessary, there are ways to rewrite the rules so that people aren't literally required to get insurance, but are incentivized so strongly that nearly everyone will do it. As an example, Congress might pass a law making state Medicaid funding dependent on states passing laws requiring residents to buy insurance. Dependent funding is something Congress does routinely, and states don't have any constitutional issues when it comes to requiring residents to buy insurance. They all do it with auto insurance and Massachusetts does it with health insurance. Or, via Ezra Klein, Congress could do something like this. There are plenty of possibilities.

So I don't think this is a big problem. It's basically a campaign issue for Republicans, who want to demonstrate to their base that they're fighting like hell against healthcare reform. It helps keep the issue alive and it helps keep the tea partiers engaged. It's sort of in the same league as their eternal promises to support a constitutional amendment to ban abortion. It's a crowd pleaser, but there's really no chance of ever pulling it off.

Averting a Health-Care Backlash from the American Prospect 8DEZ09

Copy and paste this link for the article

http://www.prospect.org/cs/articles?article=averting_a_health_care_backlash

Create a political safety-valve: let people opt out of the mandate. Just don't let them opt back in at will.

No provision of the health-care reforms being debated in Congress is as likely to generate a popular backlash as is the individual mandate -- the requirement that individuals purchase health insurance if they are not otherwise covered. But there is an alternative to the mandate as it is currently structured that can accomplish the same purpose without raising as much opposition.

The bills in Congress would impose a fine on people who decline to buy coverage after the system is reformed, unless they have a religious objection to medical care or demonstrate that paying for insurance would be a financial hardship even with the new subsidies being provided. Under the Senate bill, the fines per person would begin at $95 in 2014, rising to $750 two years later. The House bill sets the penalty at 2.5 percent of adjusted income above the threshold for filing income taxes, up to the cost of the average national premium.

The trouble with the fines is that they communicate the wrong message about a program that is supposed to help people without insurance, not penalize them. Many people simply do not understand why the government should fine them for failing to purchase health coverage when it doesn't require people to buy other products.

The rationale for the mandate is that it is necessary to carry out the other reforms of insurance that the public overwhelmingly approves -- in particular, ending pre-existing-condition exclusions by insurance companies. If legislation banned those exclusions without a mandate, healthy people would rationally refuse to buy coverage until they got sick, and the entire insurance system would break down. The mandate is designed to deter people from opportunistically dipping into the insurance funds when they are sick and refusing to contribute when they are healthy.

But Congress could address this problem more directly. The law could give people a right to opt out of the mandate if they signed a form agreeing that they could not opt in for the following five years. In other words, instead of paying a fine, they would forgo a potential benefit. For five years they would become ineligible for federal subsidies for health insurance and, if they did buy coverage, no insurer would have to cover a pre-existing condition of theirs.

The idea for this opt-out comes from an analogous provision in Germany, which has a small sector of private insurance in addition to a much larger state insurance system. Only some Germans are eligible to opt for private insurance, but if they make that choice, the law prevents them from getting back at will into the public system. That deters opportunistic switches in and out of the public funds, and it helps to prevent the private insurers from cherry-picking healthy people and driving up insurance costs in the public sector.

In the United States, an opt-out would not apply to anyone whose income was close enough to the poverty level to qualify for Medicaid. It would be available on a new income-tax form on which people with incomes above that threshold could choose between paying a fine for failing to insure or taking the five-year opt-out. (Taking the opt-out would not affect eligibility for veterans' health care, Medicare, emergency care, or any program entirely funded by a state or out of charitable donations.)

What would happen if after opting out, people got sick and couldn't pay their bills? In that case, by their own choice, they'd be back in the world that exists today. They could still try to buy insurance without a subsidy; they just wouldn't be guaranteed any insurer would take them.

The law ought to treat children, however, differently from adults. Just as there is a public interest in assuring that children receive an education, so there is a public interest in seeing that children receive health care. Instead of providing a five-year opt-out for children or imposing a fine on their parents for failing to cover them, a default program should cover any child who isn't otherwise registered for private or public insurance. That default program could be the State Children's Health Insurance Program or Medicaid; whether the parents owe any money for that coverage should be dealt with as part of the income tax.

These two measures -- a conditional opt-out for adults and default coverage for children -- could move the legislation away from an emphasis on fines as a means of enforcement and help avert a backlash. Many liberals have thought that a backlash is avoidable if subsidies for coverage are generous enough so as to allay any fears among those affected by the mandate. But whatever subsidies the law calls for, it is unrealistic to suppose that in the years before the mandate kicks in, people will have accurate information about the costs they are going to bear. The calculations are too complex, and the opponents of reform will play on that uncertainty.

An opt-out would provide an escape valve for people who feel, rationally or not, that the mandate threatens them economically. So let them opt out. Just don't let them back in at will, and over time people will learn to make use of the benefits that government subsidies and other reforms provide them.

The bill in the Senate defers the individual mandate along with most of the extension of coverage until 2014; the House postpones implementation until 2013. Some of the motivation for the slow timetable may be anxiety among Democrats in Congress about popular opposition to the mandate. But postponing reform is an ineffectual way to address that problem. The better alternative would be to provide a conditional opt-out for adults and default enrollment of children and to move up the timetable for carrying out the whole program.

By Kevin Drum

| Tue Mar. 23, 2010 8:39 AM PDT

A reader writes:

Of all the potential legal challenges to HCR out there, Ken Cuccinelli's planned lawsuit seems to me to potentially be the most viable. Assuming this issue gets to the U.S. Supreme Court, I wouldn't be a bit surprised if the (Republican majority) Roberts Court agreed with Cuccinelli. If that happens, what, exactly, is the Democrats' back-up plan?

I'm not sure what the best response to this is. Cuccinelli's suit argues that the individual mandate in the healthcare bill is unconstitutional: “We contend that if a person decides not to buy health insurance, that person — by definition — is not engaging in commerce, and therefore, is not subject to a federal mandate.” The argument here is that if it's not commerce, then it's not interstate commerce. And if it's not interstate commerce, then Congress has no constitutional authority to regulate it.

I'm not a lawyer, but this seems like the ultimate Hail Mary to me. There's longstanding precedent — hated by conservatives, but only slightly rolled back even by the Rehnquist court — that the interstate commerce clause gives Congress extremely wide power to regulate activity that affects interstate commerce in almost any way, and there's simply no question that the individual mandate is inextricably tied up with interstate commerce. The insurance industry and the medical industry are practically textbook definitions of interstate enterprises, and allowing healthy people to opt out of healthcare coverage has a very direct effect on that business. Frankly, even for an activist conservative court, this seems like a pretty open-and-shut case.

What's more, the penalties for not buying insurance are tax penalties, and if anything, Congress has even wider scope in the tax area than in the commerce area. The Supreme Court has frequently ruled that Congress can pass tax laws that essentially force people to do things that Congress doesn't have the direct power to require.

Bottom line, then: I'm not sure Democrats need a Plan B. But here's the thing: if the Supreme Court decided to overturn decades of precedent and strike down the mandate even though Kevin Drum says they shouldn't (hard to imagine, I know), the insurance industry will go ballistic. If they're required to cover all comers, even those with expensive pre-existing conditions, then they have to have a mandate in order to get all the healthy people into the insurance pool too. So they would argue very persuasively that unless Congress figures out a fix, they'll drive private insurers out of business in short order. And that, in turn, will almost certainly be enough incentive for both Democrats and Republicans to find a way to enforce a mandate by other means. If necessary, there are ways to rewrite the rules so that people aren't literally required to get insurance, but are incentivized so strongly that nearly everyone will do it. As an example, Congress might pass a law making state Medicaid funding dependent on states passing laws requiring residents to buy insurance. Dependent funding is something Congress does routinely, and states don't have any constitutional issues when it comes to requiring residents to buy insurance. They all do it with auto insurance and Massachusetts does it with health insurance. Or, via Ezra Klein, Congress could do something like this. There are plenty of possibilities.

So I don't think this is a big problem. It's basically a campaign issue for Republicans, who want to demonstrate to their base that they're fighting like hell against healthcare reform. It helps keep the issue alive and it helps keep the tea partiers engaged. It's sort of in the same league as their eternal promises to support a constitutional amendment to ban abortion. It's a crowd pleaser, but there's really no chance of ever pulling it off.

Averting a Health-Care Backlash from the American Prospect 8DEZ09

Copy and paste this link for the article

http://www.prospect.org/cs/articles?article=averting_a_health_care_backlash

Create a political safety-valve: let people opt out of the mandate. Just don't let them opt back in at will.

No provision of the health-care reforms being debated in Congress is as likely to generate a popular backlash as is the individual mandate -- the requirement that individuals purchase health insurance if they are not otherwise covered. But there is an alternative to the mandate as it is currently structured that can accomplish the same purpose without raising as much opposition.

The bills in Congress would impose a fine on people who decline to buy coverage after the system is reformed, unless they have a religious objection to medical care or demonstrate that paying for insurance would be a financial hardship even with the new subsidies being provided. Under the Senate bill, the fines per person would begin at $95 in 2014, rising to $750 two years later. The House bill sets the penalty at 2.5 percent of adjusted income above the threshold for filing income taxes, up to the cost of the average national premium.

The trouble with the fines is that they communicate the wrong message about a program that is supposed to help people without insurance, not penalize them. Many people simply do not understand why the government should fine them for failing to purchase health coverage when it doesn't require people to buy other products.

The rationale for the mandate is that it is necessary to carry out the other reforms of insurance that the public overwhelmingly approves -- in particular, ending pre-existing-condition exclusions by insurance companies. If legislation banned those exclusions without a mandate, healthy people would rationally refuse to buy coverage until they got sick, and the entire insurance system would break down. The mandate is designed to deter people from opportunistically dipping into the insurance funds when they are sick and refusing to contribute when they are healthy.

But Congress could address this problem more directly. The law could give people a right to opt out of the mandate if they signed a form agreeing that they could not opt in for the following five years. In other words, instead of paying a fine, they would forgo a potential benefit. For five years they would become ineligible for federal subsidies for health insurance and, if they did buy coverage, no insurer would have to cover a pre-existing condition of theirs.

The idea for this opt-out comes from an analogous provision in Germany, which has a small sector of private insurance in addition to a much larger state insurance system. Only some Germans are eligible to opt for private insurance, but if they make that choice, the law prevents them from getting back at will into the public system. That deters opportunistic switches in and out of the public funds, and it helps to prevent the private insurers from cherry-picking healthy people and driving up insurance costs in the public sector.

In the United States, an opt-out would not apply to anyone whose income was close enough to the poverty level to qualify for Medicaid. It would be available on a new income-tax form on which people with incomes above that threshold could choose between paying a fine for failing to insure or taking the five-year opt-out. (Taking the opt-out would not affect eligibility for veterans' health care, Medicare, emergency care, or any program entirely funded by a state or out of charitable donations.)

What would happen if after opting out, people got sick and couldn't pay their bills? In that case, by their own choice, they'd be back in the world that exists today. They could still try to buy insurance without a subsidy; they just wouldn't be guaranteed any insurer would take them.

The law ought to treat children, however, differently from adults. Just as there is a public interest in assuring that children receive an education, so there is a public interest in seeing that children receive health care. Instead of providing a five-year opt-out for children or imposing a fine on their parents for failing to cover them, a default program should cover any child who isn't otherwise registered for private or public insurance. That default program could be the State Children's Health Insurance Program or Medicaid; whether the parents owe any money for that coverage should be dealt with as part of the income tax.

These two measures -- a conditional opt-out for adults and default coverage for children -- could move the legislation away from an emphasis on fines as a means of enforcement and help avert a backlash. Many liberals have thought that a backlash is avoidable if subsidies for coverage are generous enough so as to allay any fears among those affected by the mandate. But whatever subsidies the law calls for, it is unrealistic to suppose that in the years before the mandate kicks in, people will have accurate information about the costs they are going to bear. The calculations are too complex, and the opponents of reform will play on that uncertainty.

An opt-out would provide an escape valve for people who feel, rationally or not, that the mandate threatens them economically. So let them opt out. Just don't let them back in at will, and over time people will learn to make use of the benefits that government subsidies and other reforms provide them.

The bill in the Senate defers the individual mandate along with most of the extension of coverage until 2014; the House postpones implementation until 2013. Some of the motivation for the slow timetable may be anxiety among Democrats in Congress about popular opposition to the mandate. But postponing reform is an ineffectual way to address that problem. The better alternative would be to provide a conditional opt-out for adults and default enrollment of children and to move up the timetable for carrying out the whole program.

KBR Bills $5 Million For Mechanics Who Work 43 Minutes a Month And as more GIs come home, the waste could get even worse. MOJO 25MAR10

Typical of the Pentagon, and I bet Congress will be spineless enough to let everything in place because the American people will be stupid enough to let it be and KBR will be laughing all the way to the bank....probably one that got TARP funds, paid obscene bonuses and is filing for a tax refund from the IRS. Click the header for the story and all the links at Mother Jones.

It was just a single contract for a single job on a single base in Iraq. The Department of Defense agreed to pay the megacontractor KBR $5 million a year to repair tactical vehicles, from Humvees to big rigs, at Joint Base Balad, a large airfield and supply center north of Baghdad. Yet according to a new Pentagon report, what the military got was as many as 144 civilian mechanics, each doing as little as 43 minutes of work a month, with virtually no oversight. The report, issued March 3 by the DOD's inspector general, found that between late 2008 and mid-2009, KBR performed less than 7 percent of the work it was expected to do, but still got paid in full.

The $4.6 million blown on this particular contract is a relatively small loss considering that in 2009 alone, the government had a blanket deal worth $5 billion [4] with KBR (formerly known as the Halliburton [5] subsidiary Kellogg Brown & Root). Just days before the Pentagon released the Balad report, KBR announced [6] it had won a new $2.3 billion-plus, five-year Iraq contract. But the inspector general's modest investigation offers new insight into just how little KBR delivers and how toothless the Pentagon is to prevent contractor waste. Moreover, the government's own auditors predict that as the military draws down its forces in Iraq, KBR will keep most of its workforce intact, enabling it to collect $190 million or more in unnecessary expenses. Much of any "peace dividend" [7] from the war's gradual end—potentially hundreds of billions of dollars—could wind up in the hands of contractors.

On March 29, the bipartisan Commission on Wartime Contracting [8]—which Congress set up in early 2007 to investigate waste and corruption in the military private sector—will hold a hearing to examine whether contractors are doing their part to prepare for leaving Iraq. Some commissioners are raring for a showdown with KBR over its drawdown plan—or lack thereof. The commission's co-chair, former Republican congressman Christopher H. Shays [9], said in a statement: "Considering that KBR was just awarded a task order—now under protest—that could bring them up to $2.3 billion in new [Iraq-related] revenues, it's very important that we get a clear picture of the quality of planning and oversight during the Iraq drawdown."

The Balad report is likely to be a hot potato at the hearing. Commissioner Charles Tiefer [10] tells Mother Jones the report is a "dynamite critique" of the firm's practices. "The numbers translate into an astonishingly large pool of KBR employees standing around idle and having the government be charged," he says.

What the DOD investigators found in Balad was astounding. Army rules require that its civilian maintenance employees are actively working 85 to 90 percent of the time they are on the clock. Yet KBR's own records showed that its workers were only engaged in labor an average of 6.6 percent of the time they were on duty. The DOD ran its own numbers, and its findings were even worse. In September 2008, for example, KBR had 144 maintenance employees at Balad, available to work 16,200 hours. Their actual "utilization rate" was a paltry 0.63 percent—which means that each of the 144 KBR employees averaged about 43 minutes of work for the entire month.

How did such a large bunch of thumb-twiddling mechanics go unnoticed? The Pentagon investigators found that the Army had no system in place to police how much work its contractors were actually doing. Plus, the unit in charge of KBR's operation at Balad reported that the contractor wouldn't reveal how many mechanics it employed there "because it believed the information was proprietary." The investigators (who eventually got the KBR data) note that as of last August, the number of KBR mechanics at Balad has since dropped to 75, but they conclude diplomatically that "opportunities for additional reductions of tactical vehicle field maintenance services at [Balad] may exist, which may provide additional cost savings to DOD." In other words, the Army should consider sending even more contractors home.

Some in the military appear to accept such waste as a matter of course. Col. Gust Pagonis, an assistant chief of staff for the 13th Expeditionary Sustainment Command, which took over command of Balad last August, responded to the DOD inspector general by explaining that "the contracting of maintenance capabilities, though not efficient, was effective in ensuring units did not experience low readiness rates and being able to perform the mission." Translation: The KBR contractors were essentially being kept around on reserve, just in case. Tiefer doesn't buy that argument. "That might justify a limited overcapacity, but nothing approaching KBR's levels," he says.

As the military draws down its own numbers in Iraq, that "just in case" fleet shows few signs [11] of going home. By this August, all US combat personnel are slated to be out of Iraq, leaving a force of about 50,000 "combat support" troops. Yet if the DOD's own optimistic estimates [12] are accurate, there will still be 75,000 contractors in Iraq at the end of summer—or 1.5 contractors for every soldier. KBR had 17,095 employees in Iraq as of last September, but when its subcontractors are included, it oversees as many as 58,000 workers. The firm has promised to reduce its staff in Iraq by 5 percent each quarter, but that may not be fast enough. Last November, April G. Stephenson, the then-head of the Defense Contract Audit Agency (DCAA), testified to the contracting commission [13] that KBR could cost the government another $193 million in unnecessary manpower between then and the August 2010 withdrawal date for combat forces. "When the military reduced its troop levels from 160,000 to 130,000—a 19 percent reduction—KBR's staffing levels remained constant," she told the commission, adding that KBR had so far refused to share "a detailed, written plan to reduce staffing levels in consonance with the military drawdown."

She added that the $193 million estimate was "conservative"; if KBR fails to meet its withdrawal goals, the price tag could balloon by hundreds of millions more. "The drawdown in Iraq and these Iraq task orders are going to become a deep pocket for these contractors," she told the panel. In light of the Balad report, Tiefer cautiously agrees. "If KBR has underutilized rates in many of its operations anywhere near the rates found by the inspector general study...that would support a search for savings on the order of $300 million," he says.

KBR rejects those assertions. The company has "been working since last year with these organizations in responsibly planning our support to the drawdown of military forces in Iraq," writes company spokeswoman Heather Browne in an email to Mother Jones.

Federal bean counters are concerned with more than just KBR's inflated contracts. In fiscal 2009 alone, the DCAA identified $20.4 billion in questionable billing [14], and another $12.1 billion in unsupported cost estimates, by contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan. Together, that's more money than any individual handout to the biggest beneficiaries [15] of the financial bailout.

In October, the Pentagon transferred Stephenson [16] to its payroll department. That move came after the Government Accountability Office complained [17] about auditing irregularities on Stephenson's watch. GAO even alleged that some DCAA reports had been modified to favor contractors—which suggests that the companies' waste in Iraq and Afghanistan may be even worse than already known. (Stephenson could not be reached for comment.) But even before her demotion, Stephenson's agency had little leverage with contractors. All the DCAA can do is make recommendations to an alphabet soup of other Pentagon bureaucracies that routinely insist that contracts and regulations prevent them from playing hardball with contractors and their paychecks. At the November hearing, Shays, the co-chair of the contracting commission, chastised a Defense Contract Management Agency representative for failing to withhold any payments to contractors—even after the DCAA had expressed doubts about the amounts the contractors were charging. "It is simply outrageous that DCMA did not respond to DCAA's findings and have any withholds," Shays said. "And it was unfortunate that DCAA did not have a way to see that resolved."

The DOD's inertia on contractor accountability is so complete that its agencies can't say with any certainty how many contractors are currently in Iraq and Afghanistan. One April 2009 estimate put the number at 160,000; a separate DOD study a month earlier said it was 240,000. The dysfunction has angered some Iraq War hawks, like Shays and contracting commission member Dov Zakheim [18]—a Bush-era undersecretary of defense who helped manage the war's initial finances. Zakheim upbraided several Pentagon officials in that November hearing for not keeping contractors accountable. "We've been at war for eight years in Afghanistan, long enough for me to actually start forgetting about what it was like at the beginning, when I was there," he said. "Eight years in Afghanistan, and we haven't resolved something like this, which I would have thought is absolutely critical."

But KBR will be in the hot seat at next week's hearing—and on the heels of the Balad report, that seat's now likely to be a lot hotter. "We're hoping to find out at this hearing how much progress KBR has made toward a viable drawdown plan with realistic assumptions," Tiefer says, adding: "I'm personally hoping to receive suggestions for how to reform monopoly cost-plus contracts like KBR's." Company spokeswoman Browne says KBR is ready to state its case, and is in the process of drafting a response to the inspector general's report.

For now, however, it's hard to see what the commission or the federal government can do to derail the KBR gravy train. Bases across Iraq remain dependent on the firm's contractors, and that dependency is only likely to increase as more troops come home. "In essence…we basically said that KBR is too big to fail," Shays said last May. "So we are still going to fund them."

Source URL: http://motherjones.com/politics/2010/03/kbr-idle-hands-iraq-balad-contract-waste-pentagon-report-hearing

It was just a single contract for a single job on a single base in Iraq. The Department of Defense agreed to pay the megacontractor KBR $5 million a year to repair tactical vehicles, from Humvees to big rigs, at Joint Base Balad, a large airfield and supply center north of Baghdad. Yet according to a new Pentagon report, what the military got was as many as 144 civilian mechanics, each doing as little as 43 minutes of work a month, with virtually no oversight. The report, issued March 3 by the DOD's inspector general, found that between late 2008 and mid-2009, KBR performed less than 7 percent of the work it was expected to do, but still got paid in full.

The $4.6 million blown on this particular contract is a relatively small loss considering that in 2009 alone, the government had a blanket deal worth $5 billion [4] with KBR (formerly known as the Halliburton [5] subsidiary Kellogg Brown & Root). Just days before the Pentagon released the Balad report, KBR announced [6] it had won a new $2.3 billion-plus, five-year Iraq contract. But the inspector general's modest investigation offers new insight into just how little KBR delivers and how toothless the Pentagon is to prevent contractor waste. Moreover, the government's own auditors predict that as the military draws down its forces in Iraq, KBR will keep most of its workforce intact, enabling it to collect $190 million or more in unnecessary expenses. Much of any "peace dividend" [7] from the war's gradual end—potentially hundreds of billions of dollars—could wind up in the hands of contractors.

On March 29, the bipartisan Commission on Wartime Contracting [8]—which Congress set up in early 2007 to investigate waste and corruption in the military private sector—will hold a hearing to examine whether contractors are doing their part to prepare for leaving Iraq. Some commissioners are raring for a showdown with KBR over its drawdown plan—or lack thereof. The commission's co-chair, former Republican congressman Christopher H. Shays [9], said in a statement: "Considering that KBR was just awarded a task order—now under protest—that could bring them up to $2.3 billion in new [Iraq-related] revenues, it's very important that we get a clear picture of the quality of planning and oversight during the Iraq drawdown."

The Balad report is likely to be a hot potato at the hearing. Commissioner Charles Tiefer [10] tells Mother Jones the report is a "dynamite critique" of the firm's practices. "The numbers translate into an astonishingly large pool of KBR employees standing around idle and having the government be charged," he says.

What the DOD investigators found in Balad was astounding. Army rules require that its civilian maintenance employees are actively working 85 to 90 percent of the time they are on the clock. Yet KBR's own records showed that its workers were only engaged in labor an average of 6.6 percent of the time they were on duty. The DOD ran its own numbers, and its findings were even worse. In September 2008, for example, KBR had 144 maintenance employees at Balad, available to work 16,200 hours. Their actual "utilization rate" was a paltry 0.63 percent—which means that each of the 144 KBR employees averaged about 43 minutes of work for the entire month.

How did such a large bunch of thumb-twiddling mechanics go unnoticed? The Pentagon investigators found that the Army had no system in place to police how much work its contractors were actually doing. Plus, the unit in charge of KBR's operation at Balad reported that the contractor wouldn't reveal how many mechanics it employed there "because it believed the information was proprietary." The investigators (who eventually got the KBR data) note that as of last August, the number of KBR mechanics at Balad has since dropped to 75, but they conclude diplomatically that "opportunities for additional reductions of tactical vehicle field maintenance services at [Balad] may exist, which may provide additional cost savings to DOD." In other words, the Army should consider sending even more contractors home.

Some in the military appear to accept such waste as a matter of course. Col. Gust Pagonis, an assistant chief of staff for the 13th Expeditionary Sustainment Command, which took over command of Balad last August, responded to the DOD inspector general by explaining that "the contracting of maintenance capabilities, though not efficient, was effective in ensuring units did not experience low readiness rates and being able to perform the mission." Translation: The KBR contractors were essentially being kept around on reserve, just in case. Tiefer doesn't buy that argument. "That might justify a limited overcapacity, but nothing approaching KBR's levels," he says.

As the military draws down its own numbers in Iraq, that "just in case" fleet shows few signs [11] of going home. By this August, all US combat personnel are slated to be out of Iraq, leaving a force of about 50,000 "combat support" troops. Yet if the DOD's own optimistic estimates [12] are accurate, there will still be 75,000 contractors in Iraq at the end of summer—or 1.5 contractors for every soldier. KBR had 17,095 employees in Iraq as of last September, but when its subcontractors are included, it oversees as many as 58,000 workers. The firm has promised to reduce its staff in Iraq by 5 percent each quarter, but that may not be fast enough. Last November, April G. Stephenson, the then-head of the Defense Contract Audit Agency (DCAA), testified to the contracting commission [13] that KBR could cost the government another $193 million in unnecessary manpower between then and the August 2010 withdrawal date for combat forces. "When the military reduced its troop levels from 160,000 to 130,000—a 19 percent reduction—KBR's staffing levels remained constant," she told the commission, adding that KBR had so far refused to share "a detailed, written plan to reduce staffing levels in consonance with the military drawdown."

She added that the $193 million estimate was "conservative"; if KBR fails to meet its withdrawal goals, the price tag could balloon by hundreds of millions more. "The drawdown in Iraq and these Iraq task orders are going to become a deep pocket for these contractors," she told the panel. In light of the Balad report, Tiefer cautiously agrees. "If KBR has underutilized rates in many of its operations anywhere near the rates found by the inspector general study...that would support a search for savings on the order of $300 million," he says.

KBR rejects those assertions. The company has "been working since last year with these organizations in responsibly planning our support to the drawdown of military forces in Iraq," writes company spokeswoman Heather Browne in an email to Mother Jones.

Federal bean counters are concerned with more than just KBR's inflated contracts. In fiscal 2009 alone, the DCAA identified $20.4 billion in questionable billing [14], and another $12.1 billion in unsupported cost estimates, by contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan. Together, that's more money than any individual handout to the biggest beneficiaries [15] of the financial bailout.

In October, the Pentagon transferred Stephenson [16] to its payroll department. That move came after the Government Accountability Office complained [17] about auditing irregularities on Stephenson's watch. GAO even alleged that some DCAA reports had been modified to favor contractors—which suggests that the companies' waste in Iraq and Afghanistan may be even worse than already known. (Stephenson could not be reached for comment.) But even before her demotion, Stephenson's agency had little leverage with contractors. All the DCAA can do is make recommendations to an alphabet soup of other Pentagon bureaucracies that routinely insist that contracts and regulations prevent them from playing hardball with contractors and their paychecks. At the November hearing, Shays, the co-chair of the contracting commission, chastised a Defense Contract Management Agency representative for failing to withhold any payments to contractors—even after the DCAA had expressed doubts about the amounts the contractors were charging. "It is simply outrageous that DCMA did not respond to DCAA's findings and have any withholds," Shays said. "And it was unfortunate that DCAA did not have a way to see that resolved."

The DOD's inertia on contractor accountability is so complete that its agencies can't say with any certainty how many contractors are currently in Iraq and Afghanistan. One April 2009 estimate put the number at 160,000; a separate DOD study a month earlier said it was 240,000. The dysfunction has angered some Iraq War hawks, like Shays and contracting commission member Dov Zakheim [18]—a Bush-era undersecretary of defense who helped manage the war's initial finances. Zakheim upbraided several Pentagon officials in that November hearing for not keeping contractors accountable. "We've been at war for eight years in Afghanistan, long enough for me to actually start forgetting about what it was like at the beginning, when I was there," he said. "Eight years in Afghanistan, and we haven't resolved something like this, which I would have thought is absolutely critical."

But KBR will be in the hot seat at next week's hearing—and on the heels of the Balad report, that seat's now likely to be a lot hotter. "We're hoping to find out at this hearing how much progress KBR has made toward a viable drawdown plan with realistic assumptions," Tiefer says, adding: "I'm personally hoping to receive suggestions for how to reform monopoly cost-plus contracts like KBR's." Company spokeswoman Browne says KBR is ready to state its case, and is in the process of drafting a response to the inspector general's report.

For now, however, it's hard to see what the commission or the federal government can do to derail the KBR gravy train. Bases across Iraq remain dependent on the firm's contractors, and that dependency is only likely to increase as more troops come home. "In essence…we basically said that KBR is too big to fail," Shays said last May. "So we are still going to fund them."

Source URL: http://motherjones.com/politics/2010/03/kbr-idle-hands-iraq-balad-contract-waste-pentagon-report-hearing

25 March 2010

House Gives Final Approval To Health Care Overhaul 25MAR10

In spite of all the lies and hypocrisy of the Republicans we got this done! Thank you God!!!! The first story is from NPR, the second is from the Washington Post.

Capping a bitterly fought battle over the top item on President Obama's domestic agenda, the House gave final approval to the health overhaul Thursday, after the Senate made changes and returned the measure earlier in the day.

The House voted 220-207 for bill, which now heads to President Obama for his signature. No Republicans supported the measure.

Democrats who were eager to put the long fight over health care behind them had hoped a Senate vote would finish the job. But Republicans identified problems with two provisions relating to Pell Grants for low-income students that violated the rules of the budget reconciliation process, which Democrats were using to speed the bill's passage and block a filibuster.

The provisions were stripped from the bill, and the Senate passed it on a 56-43 party line vote. No Republicans voted for the measure, and three Democrats also opposed it.

Under reconciliation rules, the legislation had to get kicked back to the House because of the changes.

Shortly before the Senate vote, President Obama delivered a message to Republicans who said they'll try to repeal his health care overhaul: "Go for it." Obama was at a campaign-style rally in Iowa to bolster support for the new law and explain what it means to average Americans.

A Barrage Of Amendments

The Senate vote followed a nine-hour marathon session stretching past 2 a.m. in which Democrats defeated 29 Republican amendments, any one of which would have sent the legislation back to the House.

Although Obama signed the health care bill into law Tuesday, the package of changes sought by the House still needed to get through the Senate. So Republicans sought to gum up the process by issuing the barrage of amendments.

One by one, Democrats voted down GOP proposals that, for example, would have rolled back cuts to Medicare and barred tax increases for families earning less than $250,000. They also defeated an amendment that would have prohibited federal money for the purchase of Viagra and other erectile dysfunction drugs for sex offenders. Sen. Tom Coburn (R-OK) introduced the amendment, saying it would save millions of dollars. Sen. Max Baucus (D-MT) called the proposed change "a crass political stunt."

"There's no attempt to improve the bill. There's an attempt to destroy this bill," Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid said.

"The majority leader may not think we're serious about changing the bill, but we'd like to change the bill, and with a little help from our friends on the other side we could improve the bill significantly," answered Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY).

Democrats noted that nearly every reconciliation bill has been subject to last-minute revisions.

Republicans And 'Armageddon'

Obama's trip to Iowa City, Iowa — where as a presidential candidate he announced his health care blueprint — was the first of many appearances around the country to sell the overhaul to voters before the fall congressional elections.

"Three years ago, I came here to this campus to make a promise," Obama told the crowd gathered at the University of Iowa, "that by the end of my first term in office, I would sign legislation to reform our health insurance system."

The president said there had been "plenty of fear-mongering and overheated rhetoric" about the health care overhaul.

"Leaders of the Republican Party, they called the passage of this bill 'Armageddon,' the end of freedom as we know it," Obama said. "So, after I signed the bill, I looked around to see if there were any asteroids falling," he said to laughter and applause.

"But from this day forward, all of the cynics and the naysayers will have to finally confront the reality of what this reform is and what it isn't," the president said.

Threats And Intimidation Tactics

As Congress wrangles with legislative details, discontent over changes to the nation's health care system has spilled over into threats of violence against lawmakers who voted for the overhaul.

The FBI is investigating at least four incidents in which bricks were thrown through the windows of Democratic offices in New York, Arizona and Kansas, including Rep. Louise Slaughter's district headquarters in Niagara Falls, N.Y. And at least 10 members of Congress reported receiving threatening e-mails, phone calls and faxes.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said at a news conference Thursday that intimidation tactics "must be rejected," adding that such behavior has "no place in a civil debate in our country."

Some of the worst threats targeted Michigan Rep. Bart Stupak, an anti-abortion Democrat who cast a key vote for the overhaul in exchange for an executive order prohibiting federal funding of abortion. One man called Stupak's office to say he hopes the congressman gets cancer and dies, while a female caller said "millions of people wish you ill" and "those thoughts will materialize into something that's not very good for you."

House Republican leader John Boehner of Ohio said in a statement that while many Americans are angry over the bill's passage, "violence and threats are unacceptable."

"That's not the American way," he said. "We need to take that anger and channel it into positive change."

Later, House Minority Whip Eric Cantor went on the offensive, saying Democratic leaders were "reckless to use these incidents as media vehicles for political gain."

Cantor said his own campaign office had been shot at and that he had received threatening e-mails this week, but didn't elaborate. He said he would not release the e-mails "because I believe such actions will encourage more to be sent."

Material from The Associated Press was used in this report

House passes reconciliation bill on 220 to 207 vote

By Lori Montgomery, Shailagh Murray and William Branigin

Washington Post Staff Writer

Thursday, March 25, 2010; 9:10 PM

Congress passed the final piece of President Obama's landmark health-care package Thursday, the last legislative hurdle in a year-long debate over the issue.

On a 220 to 207 vote Thursday night, the House approved a reconciliation bill that amends the newly enacted health-care law and includes a major overhaul of the student loan program and expansion of Pell Grants. The bill now goes to Obama for his signature.

The House vote was actually its second on the reconciliation bill. It narrowly approved the bill late Sunday night, but it came back after Republicans identified two minor violations of reconciliation rules that forced changes to a provision on student loans.

The Senate passed the reconciliation bill -- with the two small changes -- by a vote of 56 to 43.

Democratic leaders said the provisions that were struck -- from the part of the bill dealing with Pell Grants for college students -- did not significantly affect the student loan program or the overall health-care bill.

"Of all the things they could have sent back, this is probably the most benign [and] easily fixed," House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) told reporters.

Senators stood and voted from their desks as the roll was called, a tradition reserved for high-profile bills. Before the vote, the Senate observed a moment of silence for the late senator Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.), the Democratic champion of health-care reform, who died last year midway through the debate.

Three Democrats voted against the bill: Sens. Blanche Lincoln and Mark Pryor, both of Arkansas, and Sen. Ben Nelson of Nebraska. All three lawmakers supported the legislation that was signed into law on Tuesday but objected to particular provisions in the reconciliation bill.

In Iowa, Obama dared Republicans to make good on their pledge to run in November's midterm elections on a platform of repealing the health-care overhaul, telling them to "go for it" if they want to campaign on rolling back benefits he said would start taking effect this year.

The return to the House of the reconciliation bill was required after Senate parliamentarian Alan Frumin "struck two minor provisions," because they were found to violate reconciliation rules, the complicated set of procedures that protected the bill from filibuster, Jim Manley, spokesman for Senate Majority Leader Harry M. Reid (D-Nev.), told reporters shortly after 3 a.m.

Senate Budget Committee Chairman Kent Conrad (D-N.D.) said one of the deleted provisions was a technical item that he considered "as close to a 'nothing' as you can come around here." The second, more substantive provision would have set a formula for establishing maximum Pell Grant awards. But Conrad said the formula would not have taken effect for two years, giving Congress time to restore it in another bill.

Frumin deemed both measures to be out of order because they had no budget implications, Conrad said Thursday.

For much of Wednesday and into Thursday morning, Senate Republicans offered dozens of amendments, which would have altered central elements of the health-care law, but each one was rejected.

As the Senate staged a series of rapid-fire votes, only a handful of Democrats defected, suggesting that the package of changes would easily be approved in the final vote.

Although much smaller than the bill Obama has signed, the reconciliation bill makes major changes to that legislation to bring the final package in line with a compromise worked out between House and Senate leaders. Federal subsidies will be expanded slightly for people who need help buying insurance, and the coverage gap known as the doughnut hole in the Medicare prescription drug program will be closed by 2020. Seniors who fall into the doughnut hole this year will be eligible for a $250 rebate.

The measure also changes the annual penalty on individuals who do not purchase insurance to at least $695 a year or as much as 2.5 percent of annual income. And it dramatically increases the penalty facing employers who do not offer affordable coverage, to as much as $2,000 per worker.

The most significant change, however, is the method of financing the overhaul. A new 40 percent excise tax on high-cost insurance policies will be delayed until 2018 and replaced by a new tax on the nation's highest earners. Families earning more than $250,000 a year will for the first time have to pay a 3.8 percent Medicare payroll tax on capital gains, dividends and other investment income.

Staff writer Ben Pershing contributed to this report.

Capping a bitterly fought battle over the top item on President Obama's domestic agenda, the House gave final approval to the health overhaul Thursday, after the Senate made changes and returned the measure earlier in the day.

The House voted 220-207 for bill, which now heads to President Obama for his signature. No Republicans supported the measure.

Democrats who were eager to put the long fight over health care behind them had hoped a Senate vote would finish the job. But Republicans identified problems with two provisions relating to Pell Grants for low-income students that violated the rules of the budget reconciliation process, which Democrats were using to speed the bill's passage and block a filibuster.

The provisions were stripped from the bill, and the Senate passed it on a 56-43 party line vote. No Republicans voted for the measure, and three Democrats also opposed it.

Under reconciliation rules, the legislation had to get kicked back to the House because of the changes.

Shortly before the Senate vote, President Obama delivered a message to Republicans who said they'll try to repeal his health care overhaul: "Go for it." Obama was at a campaign-style rally in Iowa to bolster support for the new law and explain what it means to average Americans.

A Barrage Of Amendments

The Senate vote followed a nine-hour marathon session stretching past 2 a.m. in which Democrats defeated 29 Republican amendments, any one of which would have sent the legislation back to the House.

Although Obama signed the health care bill into law Tuesday, the package of changes sought by the House still needed to get through the Senate. So Republicans sought to gum up the process by issuing the barrage of amendments.

One by one, Democrats voted down GOP proposals that, for example, would have rolled back cuts to Medicare and barred tax increases for families earning less than $250,000. They also defeated an amendment that would have prohibited federal money for the purchase of Viagra and other erectile dysfunction drugs for sex offenders. Sen. Tom Coburn (R-OK) introduced the amendment, saying it would save millions of dollars. Sen. Max Baucus (D-MT) called the proposed change "a crass political stunt."

"There's no attempt to improve the bill. There's an attempt to destroy this bill," Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid said.

"The majority leader may not think we're serious about changing the bill, but we'd like to change the bill, and with a little help from our friends on the other side we could improve the bill significantly," answered Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY).

Democrats noted that nearly every reconciliation bill has been subject to last-minute revisions.

Republicans And 'Armageddon'

Obama's trip to Iowa City, Iowa — where as a presidential candidate he announced his health care blueprint — was the first of many appearances around the country to sell the overhaul to voters before the fall congressional elections.

"Three years ago, I came here to this campus to make a promise," Obama told the crowd gathered at the University of Iowa, "that by the end of my first term in office, I would sign legislation to reform our health insurance system."

The president said there had been "plenty of fear-mongering and overheated rhetoric" about the health care overhaul.

"Leaders of the Republican Party, they called the passage of this bill 'Armageddon,' the end of freedom as we know it," Obama said. "So, after I signed the bill, I looked around to see if there were any asteroids falling," he said to laughter and applause.

"But from this day forward, all of the cynics and the naysayers will have to finally confront the reality of what this reform is and what it isn't," the president said.

Threats And Intimidation Tactics

As Congress wrangles with legislative details, discontent over changes to the nation's health care system has spilled over into threats of violence against lawmakers who voted for the overhaul.

The FBI is investigating at least four incidents in which bricks were thrown through the windows of Democratic offices in New York, Arizona and Kansas, including Rep. Louise Slaughter's district headquarters in Niagara Falls, N.Y. And at least 10 members of Congress reported receiving threatening e-mails, phone calls and faxes.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said at a news conference Thursday that intimidation tactics "must be rejected," adding that such behavior has "no place in a civil debate in our country."

Some of the worst threats targeted Michigan Rep. Bart Stupak, an anti-abortion Democrat who cast a key vote for the overhaul in exchange for an executive order prohibiting federal funding of abortion. One man called Stupak's office to say he hopes the congressman gets cancer and dies, while a female caller said "millions of people wish you ill" and "those thoughts will materialize into something that's not very good for you."

House Republican leader John Boehner of Ohio said in a statement that while many Americans are angry over the bill's passage, "violence and threats are unacceptable."

"That's not the American way," he said. "We need to take that anger and channel it into positive change."

Later, House Minority Whip Eric Cantor went on the offensive, saying Democratic leaders were "reckless to use these incidents as media vehicles for political gain."

Cantor said his own campaign office had been shot at and that he had received threatening e-mails this week, but didn't elaborate. He said he would not release the e-mails "because I believe such actions will encourage more to be sent."

Material from The Associated Press was used in this report

House passes reconciliation bill on 220 to 207 vote

By Lori Montgomery, Shailagh Murray and William Branigin

Washington Post Staff Writer

Thursday, March 25, 2010; 9:10 PM

Congress passed the final piece of President Obama's landmark health-care package Thursday, the last legislative hurdle in a year-long debate over the issue.

On a 220 to 207 vote Thursday night, the House approved a reconciliation bill that amends the newly enacted health-care law and includes a major overhaul of the student loan program and expansion of Pell Grants. The bill now goes to Obama for his signature.

The House vote was actually its second on the reconciliation bill. It narrowly approved the bill late Sunday night, but it came back after Republicans identified two minor violations of reconciliation rules that forced changes to a provision on student loans.

The Senate passed the reconciliation bill -- with the two small changes -- by a vote of 56 to 43.

Democratic leaders said the provisions that were struck -- from the part of the bill dealing with Pell Grants for college students -- did not significantly affect the student loan program or the overall health-care bill.

"Of all the things they could have sent back, this is probably the most benign [and] easily fixed," House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) told reporters.

Senators stood and voted from their desks as the roll was called, a tradition reserved for high-profile bills. Before the vote, the Senate observed a moment of silence for the late senator Edward M. Kennedy (D-Mass.), the Democratic champion of health-care reform, who died last year midway through the debate.

Three Democrats voted against the bill: Sens. Blanche Lincoln and Mark Pryor, both of Arkansas, and Sen. Ben Nelson of Nebraska. All three lawmakers supported the legislation that was signed into law on Tuesday but objected to particular provisions in the reconciliation bill.

In Iowa, Obama dared Republicans to make good on their pledge to run in November's midterm elections on a platform of repealing the health-care overhaul, telling them to "go for it" if they want to campaign on rolling back benefits he said would start taking effect this year.