THIS is the letter I sent to the +DIANE Rehm Show WAMU on 4 SEP15

The tragic death of this child is shocking the world, but for how long? Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan are overwhelmed by the crush of refugees mainly from the Syrian civil war. Why aren't Saudi Arabia and the wealthy Gulf States doing more, providing more money and supplies to help the refugees? And one has to wonder why the refugees are they going to Europe? If Saudi Arabia and the wealthy Gulf States and even Iran are the bastions of Islam as they claim wouldn't these people be seeking refuge there? There must something drastically wrong with the state of Islam in these wealthy countries if these refugees would rather risk death to get to predominately Christian Europe than migrate to these wealthy Islamic countries. Muslims have to ask themselves what the Prophet must think about this.

I thought is was appropriate to bring this up with the saudi king visiting the White House the same day. My e mail was the first mentioned during the International Roundup portion of the show, but only the first sentence. Maybe to avoid offending the saudi monarch? Fortunately the +Washington Post has no such qualms.....

Migrants hold up a migrant man as a sign of protest against the closure of Keleti Railway Station in Budapest, Hungary, 02 September 2015. (EPA/ZOLTAN BALOGH)

The world has been transfixed in

recent weeks by the unfolding refugee crisis in Europe, an influx of

migrants unprecedented since World War II. Their plight was chillingly

highlighted on Wednesday in the image of a drowned Syrian toddler, his lifeless body lying alone on a Turkish beach.

A fair amount of attention has fallen on the failure of many Western governments to adequately address the burden on Syria's neighboring countries, which are struggling to host the brunt of the roughly 4 million Syrians forced out of the country by its civil war.

Some European countries have been criticized for offering sanctuary only to a small number of refugees, or for discriminating between Muslims and Christians. There's also been a good deal of continental hand-wringing over the general dysfunction of Europs systems for migration and asylum.

[Europe's refugee crisis is America's problem, too]

Less ire, though, has been directed at another set of stakeholders who almost certainly should be doing more: Saudi Arabia and the wealthy Arab states along the Persian Gulf.

As Amnesty International recently pointed out, the "six Gulf countries -- Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman and Bahrain -- have offered zero resettlement places to Syrian refugees." This claim was echoed by Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, on Twitter:

The way that Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states aid Syrian refugees:

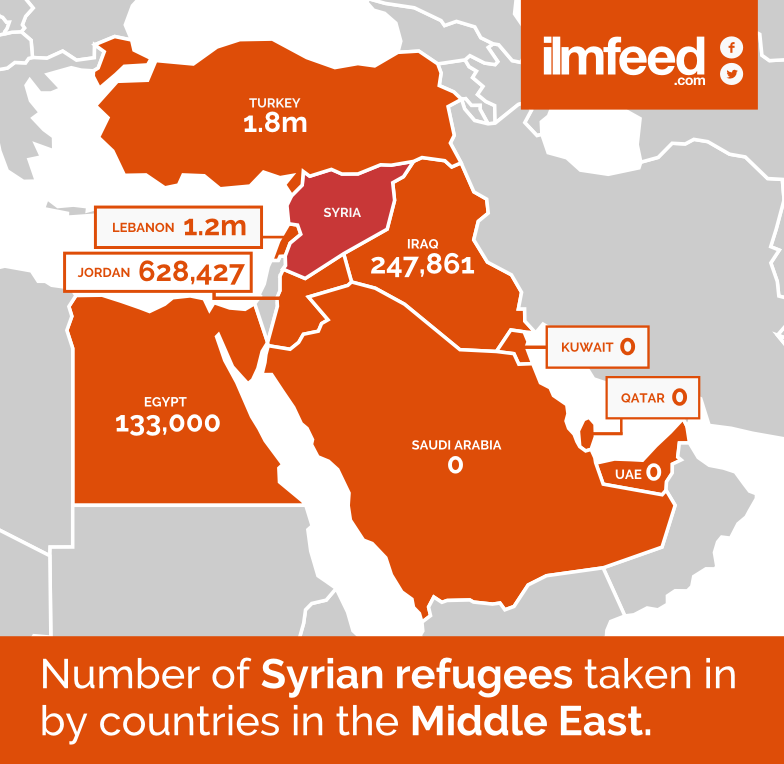

Or see this map tweeted by Luay Al Khatteeb, a nonresident fellow at the Brookings Institution, showing the numbers accommodated by Syria's overwhelmed neighbors in comparison to the oil-rich states further south:

That's a shocking figure, given these countries' relative proximity to Syria, as well as the incredible resources at their disposal. As Sultan Sooud al-Qassemi, a Dubai-based political commentator, observes, these countries include some of the Arab world's largest military budgets, its highest standards of living, as well as a lengthy history -- especially in the case of the United Arab Emirates -- of welcoming immigrants from other Arab nations and turning them into citizens.

Moreover, these countries aren't totally innocent bystanders. To varying degrees, elements within Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the U.A.E. and Kuwait have invested in the Syrian conflict, playing a conspicuous role in funding and arming a constellation of rebel and Islamist factions fighting the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

None of these countries are signatories of the United Nations' 1951 Refugee Convention, which defines what a refugee is and lays out their rights, as well as the obligations of states to safeguard them. For a Syrian to enter these countries, they would have to apply for a visa, which, in the current circumstances, is rarely granted. According to the BBC, the only Arab countries where a Syrian can travel without a visa are Algeria, Mauritania, Sudan and Yemen -- hardly choice or practical destinations.

A spokesperson for UNHCR, the U.N.'s refugee agency, told Bloomberg that there are roughly 500,000 Syrians living in Saudi Arabia, though they are not classified as refugees and it's not clear when the majority of them arrived in the country.

Like European countries, Saudi Arabia and its neighbors also have fears over new arrivals taking jobs from citizens, and may also invoke concerns about security and terrorism. But the current gulf aid outlay for Syrian refugees, which amounts to collective donations under $1 billion (the United States has given four times that sum), seems short -- and is made all the more galling when you consider the vast sums Saudi Arabia and the U.A.E. poured into this year's war effort in Yemen, an intervention some consider a strategic blunder.

As Bobby Ghosh, managing editor of the news site Quartz, points out, the gulf states in theory have a far greater ability to deal with large numbers of arrivals than Syria's more immediate and poorer neighbors, Lebanon and Jordan:

"The Gulf must realize that now is the time to change their policy regarding accepting refugees from the Syria crisis," writes the columnist Qassemi. "It is the moral, ethical and responsible step to take."

Read more:

Europe’s fear of Muslim refugees echoes 1930s anti-Semitism

Hungarian leader invokes Ottoman invasion to justify thwarting refugees

When the West wanted Islam to curb Christian extremism

Black route: One family's journey from Aleppo to Austria

Smugglers who drove migrants to their deaths were part of a vast web

Read The Post’s coverage on the global surge in migration

President

Obama has not been easy on the Saudi royal family. He riled Saudi

royals by saying that the “biggest threats” to America’s Arab allies may

not emanate from longtime foe Iran but from their own youths chafing

under restrictive rule.

The president took that critique a step further in July when he confided that he “weeps for the children” of the Middle East. “Not just the ones who are being displaced in Syria,” Obama told the New York Times, “but just the ordinary Iranian youth or Saudi youth or Kuwaiti youth” who don’t have the same prospects as children in Europe and Asia.

When Obama met Friday with visiting King Salman of Saudi Arabia, the focus was on stemming the violence that has swept through the Middle East in recent years. “We share a concern about Yemen and the need to restore a functioning government that is inclusive there,” Obama said in brief remarks from the Oval Office. The king and the president talked about the “horrific conflict” in Syria, the battle against the Islamic State and how to counter Iran’s “destabilizing action,” Obama said.

The focus, at least in the president’s public remarks, was on common interests. “I doubt that the president will be that blunt in the Oval Office” in his criticism of the Saudis, said Prem Kumar, a former top White House adviser on the Middle East and now a vice president at the Albright Stonebridge Group, a global strategy firm. “He will want to know where Saudi Arabia is heading.”

Speaking from the Oval Office, Obama made no mention of his concern about the repressive political culture inside Saudi Arabia or the potential for unrest among its young people. Salman, who four months ago declined the president’s invitation to visit Camp David, similarly seemed eager to sidestep differences between the two nations over the nuclear negotiations with Iran.

In recent months, the Obama administration has dispatched Defense Secretary Ashton B. Carter and Secretary of State John F. Kerry to Riyadh to allay concerns about the nuclear deal. The high-level delegations helped persuade the Saudis to support the final deal with Iran, even as they have continued to express a fear that the lifting of sanctions will provide Tehran with a financial windfall that can be used to strengthen its conventional military and proxy forces.

“The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia was satisfied with these

assurances after having spent the last two months consulting with our

allies,” said Saudi Foreign Minister Adel al-Jubeir. He said that the

agreement should allow the world to focus “with greater intensity” on

Iran’s “nefarious activities” in the Middle East.

One of the administration’s top aims, meanwhile, is to persuade its Arab allies in the Persian Gulf to play a more active role in restoring order in the region. The relief from sanctions that is part of the Iran nuclear deal is expected to net Iran about $56 billion in the near term. The president has suggested that the Iranians will have to use much of that to repair crumbling infrastructure and revive an economy battered by the sanctions.

Even if Iran pumps a large amount of that money into its military, it will still spend vastly less than the United States’ Arab allies, said Ben Rhodes, a deputy national security adviser.

“The defense budget of our gulf partners is more than eight times that of Iran,” Rhodes said in a briefing for reporters. “There’s no amount of sanctions relief that could even begin to close that gap.”

Administration officials said they do not expect any major U.S. announcements regarding weapons sales to Saudi Arabia. Rather, they would like to see the Saudis invest more in relatively inexpensive weaponry and training that can counter the unconventional threats posed by Iran and its proxies, such as the Lebanon-based Shiite militant movement Hezbollah. The White House has been encouraging the Saudis to focus more on building up their special forces, sharing intelligence and cooperating with gulf allies in areas such as cybersecurity and missile defense, instead of buying costly fighter jets or attack helicopters, Rhodes said.

For months, conversations between U.S. and Saudi officials have been consumed by the Iran nuclear deal. Now the focus is turning to “what’s next in the region after the Iran deal,” said Matt Spence, a former deputy assistant secretary of defense for the Middle East in the Obama administration. Much of that conversation will focus on Yemen, where the Saudis are leading a coalition of gulf allies battling Houthi rebels who are backed by Iran.

The Obama administration has applauded the Saudis for taking the initiative in battling the rebels, but at the same time it has fretted over the destruction that the Saudi-led campaign is causing.

The United States has cautioned the Saudis, along with the other combatants, about the growing humanitarian crisis in Yemen. “What we have been doing is urging all of the parties involved . . . to take steps to allow for unfettered humanitarian access to all parts of Yemen,” said Jeffrey Prescott, senior director for the Middle East in the White House.

The tragic death of this child is shocking the world, but for how long? Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan are overwhelmed by the crush of refugees mainly from the Syrian civil war. Why aren't Saudi Arabia and the wealthy Gulf States doing more, providing more money and supplies to help the refugees? And one has to wonder why the refugees are they going to Europe? If Saudi Arabia and the wealthy Gulf States and even Iran are the bastions of Islam as they claim wouldn't these people be seeking refuge there? There must something drastically wrong with the state of Islam in these wealthy countries if these refugees would rather risk death to get to predominately Christian Europe than migrate to these wealthy Islamic countries. Muslims have to ask themselves what the Prophet must think about this.

I thought is was appropriate to bring this up with the saudi king visiting the White House the same day. My e mail was the first mentioned during the International Roundup portion of the show, but only the first sentence. Maybe to avoid offending the saudi monarch? Fortunately the +Washington Post has no such qualms.....

The Arab world’s wealthiest nations are doing next to nothing for Syria’s refugees

Migrants hold up a migrant man as a sign of protest against the closure of Keleti Railway Station in Budapest, Hungary, 02 September 2015. (EPA/ZOLTAN BALOGH)

A fair amount of attention has fallen on the failure of many Western governments to adequately address the burden on Syria's neighboring countries, which are struggling to host the brunt of the roughly 4 million Syrians forced out of the country by its civil war.

Some European countries have been criticized for offering sanctuary only to a small number of refugees, or for discriminating between Muslims and Christians. There's also been a good deal of continental hand-wringing over the general dysfunction of Europs systems for migration and asylum.

[Europe's refugee crisis is America's problem, too]

Less ire, though, has been directed at another set of stakeholders who almost certainly should be doing more: Saudi Arabia and the wealthy Arab states along the Persian Gulf.

As Amnesty International recently pointed out, the "six Gulf countries -- Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman and Bahrain -- have offered zero resettlement places to Syrian refugees." This claim was echoed by Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, on Twitter:

Guess how many of these Syrian refugees Saudi Arabia & other Gulf states offered to take?

0

http://bit.ly/1KrN5Rw

Or see this map tweeted by Luay Al Khatteeb, a nonresident fellow at the Brookings Institution, showing the numbers accommodated by Syria's overwhelmed neighbors in comparison to the oil-rich states further south:

That's a shocking figure, given these countries' relative proximity to Syria, as well as the incredible resources at their disposal. As Sultan Sooud al-Qassemi, a Dubai-based political commentator, observes, these countries include some of the Arab world's largest military budgets, its highest standards of living, as well as a lengthy history -- especially in the case of the United Arab Emirates -- of welcoming immigrants from other Arab nations and turning them into citizens.

Moreover, these countries aren't totally innocent bystanders. To varying degrees, elements within Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the U.A.E. and Kuwait have invested in the Syrian conflict, playing a conspicuous role in funding and arming a constellation of rebel and Islamist factions fighting the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

None of these countries are signatories of the United Nations' 1951 Refugee Convention, which defines what a refugee is and lays out their rights, as well as the obligations of states to safeguard them. For a Syrian to enter these countries, they would have to apply for a visa, which, in the current circumstances, is rarely granted. According to the BBC, the only Arab countries where a Syrian can travel without a visa are Algeria, Mauritania, Sudan and Yemen -- hardly choice or practical destinations.

A spokesperson for UNHCR, the U.N.'s refugee agency, told Bloomberg that there are roughly 500,000 Syrians living in Saudi Arabia, though they are not classified as refugees and it's not clear when the majority of them arrived in the country.

Like European countries, Saudi Arabia and its neighbors also have fears over new arrivals taking jobs from citizens, and may also invoke concerns about security and terrorism. But the current gulf aid outlay for Syrian refugees, which amounts to collective donations under $1 billion (the United States has given four times that sum), seems short -- and is made all the more galling when you consider the vast sums Saudi Arabia and the U.A.E. poured into this year's war effort in Yemen, an intervention some consider a strategic blunder.

As Bobby Ghosh, managing editor of the news site Quartz, points out, the gulf states in theory have a far greater ability to deal with large numbers of arrivals than Syria's more immediate and poorer neighbors, Lebanon and Jordan:

The region has the capacity to quickly build housing for the refugees. The giant construction companies that have built the gleaming towers of Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and Riyadh should be contracted to create shelters for the influx. Saudi Arabia has plenty of expertise at managing large numbers of arrivals: It receives an annual surge of millions of Hajj pilgrims to Mecca. There’s no reason all this knowhow can’t be put to humanitarian use.No reason other than either indifference or a total lack of political will. In social media, many are calling for action. The Arabic hashtag #Welcoming_Syria's_refugees_is_a_Gulf_duty was tweeted more than 33,000 times in the past week, according to the BBC.

"The Gulf must realize that now is the time to change their policy regarding accepting refugees from the Syria crisis," writes the columnist Qassemi. "It is the moral, ethical and responsible step to take."

Read more:

Europe’s fear of Muslim refugees echoes 1930s anti-Semitism

Hungarian leader invokes Ottoman invasion to justify thwarting refugees

When the West wanted Islam to curb Christian extremism

Black route: One family's journey from Aleppo to Austria

Smugglers who drove migrants to their deaths were part of a vast web

Read The Post’s coverage on the global surge in migration

Ishaan

Tharoor writes about foreign affairs for The Washington Post. He

previously was a senior editor at TIME, based first in Hong Kong and

later in New York.

Saudi king visits U.S. with Iran deal and Yemen as major mutual concerns

President

Obama welcomed King Salman of Saudi Arabia to the White House on Sept.

4, 2015, outlining a broad range of discussions they will have on the

Middle East, including the Iran nuclear deal and the civil war in Yemen.

(AP)

The president took that critique a step further in July when he confided that he “weeps for the children” of the Middle East. “Not just the ones who are being displaced in Syria,” Obama told the New York Times, “but just the ordinary Iranian youth or Saudi youth or Kuwaiti youth” who don’t have the same prospects as children in Europe and Asia.

When Obama met Friday with visiting King Salman of Saudi Arabia, the focus was on stemming the violence that has swept through the Middle East in recent years. “We share a concern about Yemen and the need to restore a functioning government that is inclusive there,” Obama said in brief remarks from the Oval Office. The king and the president talked about the “horrific conflict” in Syria, the battle against the Islamic State and how to counter Iran’s “destabilizing action,” Obama said.

The focus, at least in the president’s public remarks, was on common interests. “I doubt that the president will be that blunt in the Oval Office” in his criticism of the Saudis, said Prem Kumar, a former top White House adviser on the Middle East and now a vice president at the Albright Stonebridge Group, a global strategy firm. “He will want to know where Saudi Arabia is heading.”

Speaking from the Oval Office, Obama made no mention of his concern about the repressive political culture inside Saudi Arabia or the potential for unrest among its young people. Salman, who four months ago declined the president’s invitation to visit Camp David, similarly seemed eager to sidestep differences between the two nations over the nuclear negotiations with Iran.

In recent months, the Obama administration has dispatched Defense Secretary Ashton B. Carter and Secretary of State John F. Kerry to Riyadh to allay concerns about the nuclear deal. The high-level delegations helped persuade the Saudis to support the final deal with Iran, even as they have continued to express a fear that the lifting of sanctions will provide Tehran with a financial windfall that can be used to strengthen its conventional military and proxy forces.

One of the administration’s top aims, meanwhile, is to persuade its Arab allies in the Persian Gulf to play a more active role in restoring order in the region. The relief from sanctions that is part of the Iran nuclear deal is expected to net Iran about $56 billion in the near term. The president has suggested that the Iranians will have to use much of that to repair crumbling infrastructure and revive an economy battered by the sanctions.

Even if Iran pumps a large amount of that money into its military, it will still spend vastly less than the United States’ Arab allies, said Ben Rhodes, a deputy national security adviser.

“The defense budget of our gulf partners is more than eight times that of Iran,” Rhodes said in a briefing for reporters. “There’s no amount of sanctions relief that could even begin to close that gap.”

Administration officials said they do not expect any major U.S. announcements regarding weapons sales to Saudi Arabia. Rather, they would like to see the Saudis invest more in relatively inexpensive weaponry and training that can counter the unconventional threats posed by Iran and its proxies, such as the Lebanon-based Shiite militant movement Hezbollah. The White House has been encouraging the Saudis to focus more on building up their special forces, sharing intelligence and cooperating with gulf allies in areas such as cybersecurity and missile defense, instead of buying costly fighter jets or attack helicopters, Rhodes said.

For months, conversations between U.S. and Saudi officials have been consumed by the Iran nuclear deal. Now the focus is turning to “what’s next in the region after the Iran deal,” said Matt Spence, a former deputy assistant secretary of defense for the Middle East in the Obama administration. Much of that conversation will focus on Yemen, where the Saudis are leading a coalition of gulf allies battling Houthi rebels who are backed by Iran.

The Obama administration has applauded the Saudis for taking the initiative in battling the rebels, but at the same time it has fretted over the destruction that the Saudi-led campaign is causing.

The United States has cautioned the Saudis, along with the other combatants, about the growing humanitarian crisis in Yemen. “What we have been doing is urging all of the parties involved . . . to take steps to allow for unfettered humanitarian access to all parts of Yemen,” said Jeffrey Prescott, senior director for the Middle East in the White House.

Greg Jaffe covers the White House for The Washington Post, where he has been since March 2009.

Kenneth Roth

Kenneth Roth Luay لؤي الخطيب

Luay لؤي الخطيب

No comments:

Post a Comment