WHAT A LADY!!! Thank you for your service Dr Walker!!! You were a remarkable woman, doctor, human being and American veteran. I am so glad you didn't return your well deserved Medal of Honor and am very glad you took it with you to your grave so the government can never take it back!

They stripped her Medal of Honor in 1917. She refused to return it, wearing it daily on her men's suit until she died in 1919. It was restored 58 years later. She was right all along.

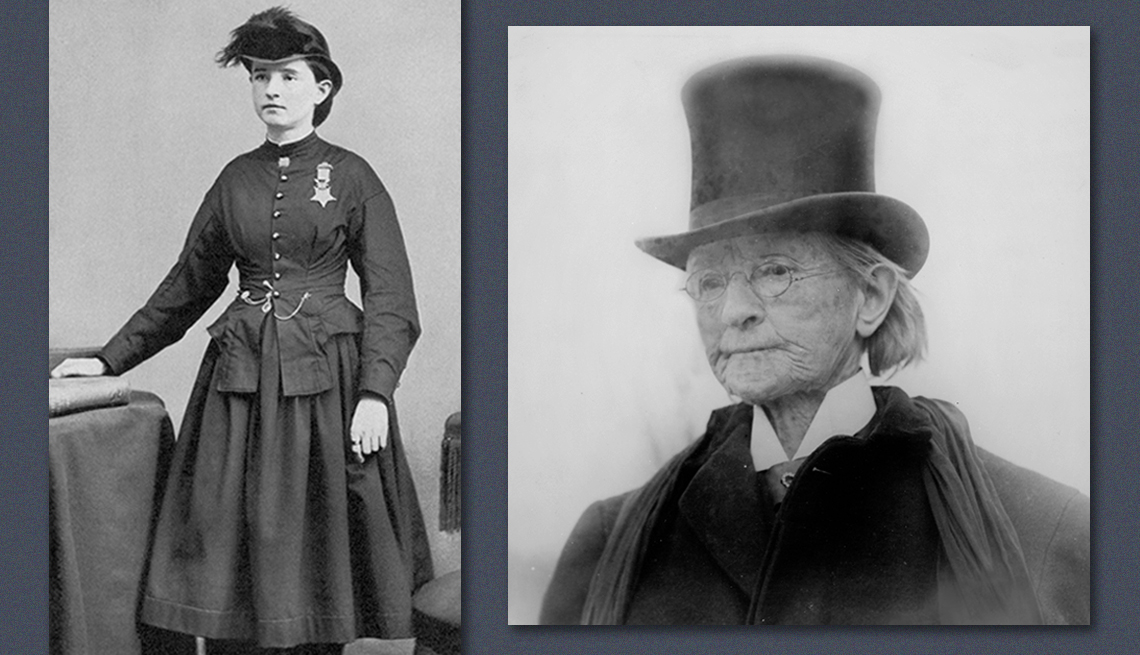

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker was the only woman ever awarded the Medal of Honor. The U.S. government tried to take it back. She told them to go to hell—not in those words exactly, but in every action for the rest of her life.

She was born November 26, 1832, on a farm in Oswego, New York. Her parents were abolitionists and educational reformers who believed daughters deserved the same opportunities as sons. Radical idea for 1832. Mary's father taught her carpentry, mechanics, and medicine. Her mother taught her that corsets were instruments of torture designed to keep women weak.

Mary rejected corsets at age 15. She started wearing "reform dress"—shorter skirts over trousers, modeled after Turkish women's clothing. She was mocked constantly. She didn't care. She'd decided that fashion designed to restrict women's movement was fashion designed to restrict women's lives.

At 21, she enrolled in Syracuse Medical College. One of the only women in America pursuing medical education. Her male classmates harassed her. Professors questioned whether women had the intellectual capacity for medicine. She graduated in 1855 with her M.D.—one of the first women doctors in the United States.

Then she discovered that having a medical degree meant nothing if no one would hire you.

She opened a private practice with her husband, Albert Miller (also a doctor). Patients refused to see a female doctor. The practice failed. Her marriage failed too—Miller had affairs, and Mary divorced him in 1869. Scandalous for the era. She kept her maiden name. Even more scandalous.

By 1861, Mary was 28, divorced, struggling financially, and then the Civil War started. She saw opportunity.

She traveled to Washington D.C. and volunteered as a surgeon for the Union Army. The Army said no. Women could be nurses—cleaning, cooking, comforting. Not surgeons. Not officers. Not equals.

Mary went to the front anyway. Unpaid. Unofficial. She set up near battlefields and treated whoever needed help. After the First Battle of Bull Run (July 1861), she worked in a temporary hospital in the Patent Office building, treating hundreds of wounded soldiers.

Army officials couldn't deny she was skilled. In 1862, they hired her—as a nurse. She took the job because it got her near the wounded. But she didn't just nurse—she diagnosed, prescribed, operated. Surgeons who initially resented her began requesting her assistance.

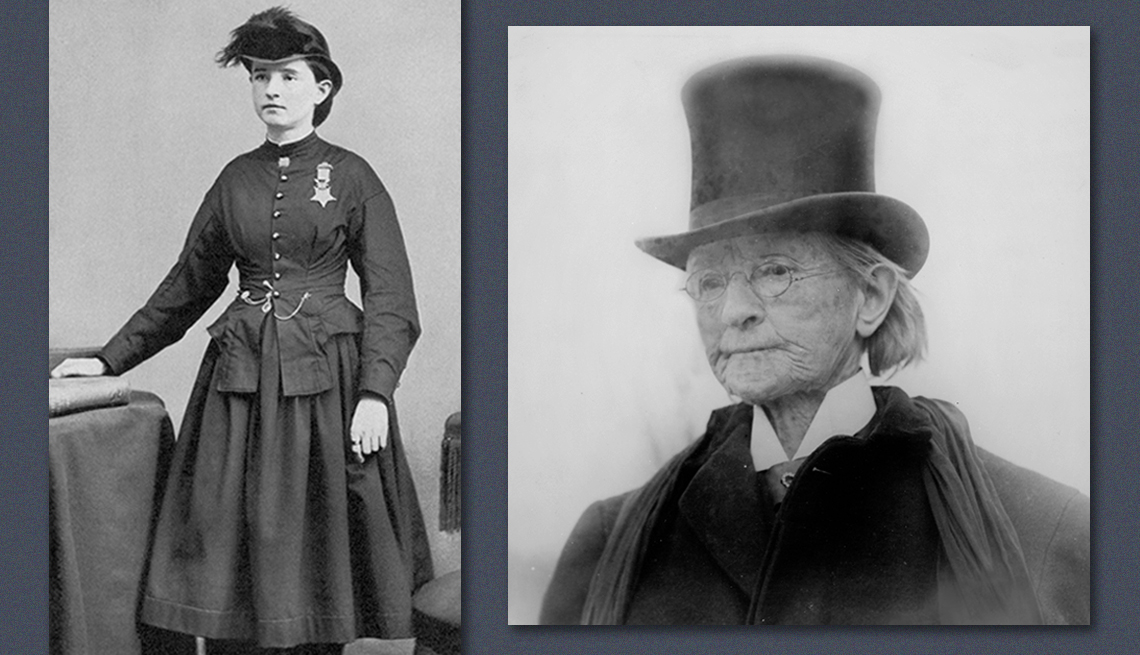

She also wore what she wanted: modified officer's uniform with trousers. Male officers complained. She ignored them. "I don't wear men's clothes," she said. "I wear my own clothes."

For two years, she worked in field hospitals, often under fire. She assisted in surgeries where men screamed and limbs were sawed off without anesthesia (supplies were limited). She walked through battlefields pulling wounded men to safety. She contracted typhoid fever and nearly died. She recovered and returned to work.

In September 1863, she was finally appointed as Army surgeon—civilian contract, but official recognition. She was assigned to the 52nd Ohio Infantry. She became the first female U.S. Army surgeon.

But Mary wanted to do more. She started crossing into Confederate territory to treat civilian wounded—women, children, elderly left behind in war zones. Dangerous work. She was a Union officer behind enemy lines.

On April 10, 1864, near Chattanooga, Tennessee, Confederate soldiers captured her. They accused her of being a spy. She wasn't—she was treating civilians. But she was wearing a Union officer's uniform in Confederate territory, so they imprisoned her.

She was held at Castle Thunder in Richmond, Virginia—a notorious Confederate prison. Conditions were brutal: overcrowded, disease-ridden, minimal food. Male prisoners of war were beaten and starved. Mary, as the only female officer prisoner, was kept in slightly better conditions (separate cell) but still endured four months of hunger, isolation, and uncertainty.

In August 1864, she was released in a prisoner exchange—traded for a Confederate officer. She'd lost significant weight and her health was damaged permanently. She returned to duty immediately.

November 11, 1865: President Andrew Johnson awarded Mary Edwards Walker the Medal of Honor for her service during the Civil War. The citation praised her "valuable service" including "devoted[ness] to the sick and wounded" and her capture while "furnishing medical assistance to the wounded."

She was the first and only woman to receive it. She wore it every day for the rest of her life.

After the war, Mary became a writer, lecturer, and activist. She campaigned for:

Women's suffrage (right to vote—wouldn't be achieved until 1920)

Dress reform (opposed corsets, promoted practical clothing for women)

Women's property rights (married women couldn't own property in many states)

Temperance (alcohol prohibition—she'd seen alcohol destroy families)

She was considered eccentric, radical, difficult. She wore full men's suits with top hat. She was arrested multiple times for "impersonating a man" (it was illegal in some cities for women to wear trousers). She'd show up in court wearing her Medal of Honor and lecture the judge about women's rights.

People mocked her. Newspapers called her "a crazy woman in men's clothes." Cartoonists drew cruel caricatures. She didn't stop. She gave speeches across the country, wrote books, testified before Congress.

Congress passed a law revising Medal of Honor standards. They wanted to make it more exclusive—only for combat valor involving "risk of life above and beyond the call of duty" in direct combat with enemy forces.

They reviewed all previous recipients. They revoked 911 medals—mostly Civil War era awards given for non-combat service. Mary's was among them.

The Army Board for Correction of Military Records sent her a letter: return the medal.

Mary Edwards Walker, 84 years old, wrote back: No.

She wore it every day until she died. On her suit lapel. To lectures. To the grocery store. Everywhere. Pinned over her heart like armor.

She died February 21, 1919, at age 86. She'd tripped on the steps of the Capitol building (she was there lobbying for women's suffrage) and never fully recovered.

She was buried in her black suit, with her Medal of Honor pinned to her chest.

For 58 years, the revocation stood. Mary Edwards Walker was officially not a Medal of Honor recipient, despite the medal being buried with her, despite her service, despite everything.

Then, in 1977, a campaign by her descendants and supporters reached President Jimmy Carter. He reviewed her service record. On June 10, 1977, Carter signed legislation restoring her Medal of Honor.

She remains the only woman ever awarded the Medal of Honor.

Here's what her story actually shows:

She wasn't recognized because she was exceptional. She was exceptional despite never being recognized—at least not in her lifetime. She served as a surgeon for years before the Army officially acknowledged it. She received the Medal of Honor, then had it stripped, then restored 58 years after her death.

She spent her entire life fighting for the right to simply exist as she was: a woman who wore practical clothes, practiced medicine, spoke her mind, and refused to apologize.

The world called her crazy. History calls her right.

Every woman who became a military surgeon after her walked a path Mary cleared—usually without credit. Every woman who wears pants without arrest walks in freedom Mary fought for. Every female Medal of Honor debate references the woman who wouldn't give hers back.

She didn't wait for permission. She didn't wait for society to approve. She didn't wait for the rules to change.

She just lived as if the rules didn't apply to her. And eventually—decades after her death—the world admitted she'd been right.

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker died in 1919 wearing the medal they'd tried to take. She was buried with it pinned to her chest. And in 1977, the United States government finally admitted: she'd earned it all along.

She was the only woman to receive the Medal of Honor. They tried to take it back. She refused.

And 58 years after she died, they admitted she'd been right to refuse.

Sometimes being ahead of your time means dying before your time catches up. But it catches up eventually.

And when it does, the medal's still pinned to your chest—exactly where you knew it belonged.

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker was a woman of immense courage, intellect, and resilience. Her story is one that was long overlooked but is now finally being recognized for its profound impact on American history. As the only woman to ever be awarded the Medal of Honor, Mary’s life was marked by extraordinary accomplishments, unshakable determination, and a lifelong fight for women’s rights and gender equality.

From defying societal norms by wearing pants at a time when it was considered illegal for women to do so, to serving as a surgeon during the Civil War in ways that changed the course of American military history, Dr. Walker was a true trailblazer. But even more impressive than her academic, medical, and activist achievements was her unrelenting spirit — a spirit that continued to challenge gender expectations and fight for her rightful place in history, even long after her death.

Early Life and EducationMary Edwards Walker was born on November 26, 1832, in Oswego, New York, to a family that embraced progressive ideals for the time. Her parents were abolitionists and believed in providing equal opportunities for both sons and daughters. From an early age, Mary was encouraged to pursue education, a rarity for girls in the 19th century. Her father taught her carpentry, mechanics, and medicine, ensuring that she had a well-rounded education far beyond what was typical for women.

Her early exposure to these fields would lay the groundwork for her future endeavors. Mary Edwards Walker’s desire to forge a path for herself in male-dominated industries was a sign of the defiance and persistence that would characterize her entire life.

Breaking Boundaries: Education and Early Medical Career

At the age of 21, Mary Edwards Walker enrolled in Syracuse Medical College, becoming one of the first women in America to pursue a medical degree. The journey was far from easy. She faced harassment from male classmates and professors who questioned whether women had the intellectual capacity to practice medicine. Despite the discrimination, she graduated with a medical degree in 1855, further proving that gender should not determine a person’s capabilities.

However, having earned a medical degree was only the first challenge Mary faced. After completing her studies, Mary discovered that the medical profession wasn’t ready to accept female doctors. Doors remained closed to her, and most patients refused to see a woman doctor. In 1856, she married Dr. Albert Miller, a fellow physician, and together they opened a medical practice. Unfortunately, the marriage was short-lived, and the practice failed.

In 1869, Mary, fed up with her marriage and unable to continue in the practice, filed for divorce — a bold and scandalous move at the time. She kept her maiden name, another controversial choice, and continued her work as an independent woman in a society that expected women to submit to the will of their husbands.

The Civil War and Mary’s Role as a Surgeon

With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Mary Edwards Walker saw an opportunity to make a difference. The Union Army initially rejected her offer to serve as a surgeon, claiming that women were only fit to be nurses. But Mary, undeterred by these constraints, didn’t accept no for an answer. She volunteered to work on the battlefield and treated soldiers without pay, demonstrating the immense value she could bring to the Union’s war effort.

It wasn’t long before Mary’s skills were recognized, and in 1862, she was appointed a contract surgeon by the Union Army, becoming the first female surgeon in U.S. military history. Her work involved treating wounded soldiers, assisting in surgeries, and offering medical advice. Though often working in battlefield hospitals under hazardous conditions, Mary continued to serve despite the lack of recognition from her male counterparts.

Notably, she rejected the typical female roles of nurses and caregivers, instead stepping directly into a position that had been exclusively held by men. Mary’s courageous approach to working in the field alongside men and her expertise as a surgeon made her an indispensable member of the Union’s medical team.

A Captive and Continued Service

In 1864, Mary Edwards Walker was captured by Confederate soldiers after she ventured into Confederate territory to treat civilians wounded in the war. She was accused of being a spy, a claim that held no truth. As a result, she was imprisoned at Castle Thunder in Richmond, Virginia, where conditions were brutal. Despite being the only female prisoner, Mary endured hunger, isolation, and uncertainty for several months before being released in a prisoner exchange.

Following her release, Mary Edwards Walker resumed her work with the Union Army, demonstrating the same dedication to the cause as she had before her capture. In 1865, President Andrew Johnson awarded her the Medal of Honor for her courageous service. She became the first and only woman to receive this prestigious military award, recognized for her tireless efforts to aid the sick and wounded during the Civil War. Her contribution to the war effort and her groundbreaking role in the medical field were finally acknowledged.

Advocacy and Activism After the War

After the Civil War, Mary Edwards Walker didn’t rest on her laurels. She became a prominent activist, advocating for several important social causes, including women’s suffrage, dress reform, and the temperance movement. She believed women should have the right to vote and be recognized as equals in every facet of life, including the workplace.

Mary also fought against the restrictive societal norms of the time. She famously wore men’s clothing, rejecting the traditional dresses and corsets that she saw as tools of oppression. This bold move earned her scorn from society, but she didn’t back down. She also faced several legal challenges for “impersonating a man” as it was considered illegal for women to wear pants in some cities.

Her activism wasn’t limited to her wardrobe; she campaigned for women’s property rights, where married women couldn’t legally own property in many states. She was a fierce advocate for the rights of women and believed that societal change would come only when women were free to live and work on their own terms.

The Revocation and Restoration of the Medal of Honor

In 1917, Congress passed a law revising the criteria for the Medal of Honor, and many recipients from the Civil War era were stripped of their awards. Unfortunately, Mary Edwards Walker’s medal was among those revoked. The reason cited was that the medal was meant for combat valor, involving “risk of life above and beyond the call of duty,” and Mary’s contributions were considered non-combatant.

Mary, however, refused to return her Medal of Honor. She wore it every day for the rest of her life as a symbol of her unyielding service and commitment. She passed away in 1919 at the age of 86, and she was buried with the medal pinned to her chest.

Fifty-eight years later, after much advocacy from her descendants and supporters, President Jimmy Carter signed legislation restoring her Medal of Honor in 1977. Mary Edwards Walker remains the only woman ever awarded the Medal of Honor, and her name has been forever etched in history.

Legacy and RecognitionMary Edwards Walker’s story is one of resilience, defiance, and unwavering commitment to equality. She faced immense challenges and discrimination throughout her life, yet she never stopped fighting for herself and for others. As a doctor, activist, and military surgeon, she broke barriers and redefined what it meant to be a woman in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Her legacy lives on through the countless women who followed in her footsteps, becoming doctors, military personnel, and advocates for social change. She taught us all that true courage isn’t just about what we do in the face of danger, but also about how we challenge the status quo and demand equality, respect, and recognition.

In a world that often seems divided, Mary Edwards Walker’s life reminds us that change is possible—sometimes, it just takes a courageous individual willing to risk everything to make it happen. Her Medal of Honor may have been stripped once, but the respect and admiration for her service will never be erased. She was a pioneer, and her story is a testament to the power of resilience, determination, and the belief that everyone, regardless of gender, deserves to be seen and heard.

Conclusion

Mary Edwards Walker’s life and legacy serve as a profound reminder of what it means to truly challenge societal norms, to persist against adversity, and to fight for what is right. As the first woman to receive the Medal of Honor, she not only changed the landscape of American military history but also paved the way for future generations of women to break through barriers in every field. Her courage, tenacity, and vision continue to inspire us today as we strive for a world where equality and justice prevail.

Let us remember her not just as the woman who defied convention, but as the woman who helped change the course of history with her compassion, intelligence, and unyielding belief in the right to live freely, without restraint.

No comments:

Post a Comment