HERE'S a man who is willing to defy fuhrer wanna-be NOT MY pres drumpf/trump, just like August Landmesser, the man who refused to salute hitler in 1936. Oh that we witness more of this until the fascist reign of drumpf/trump-pence is over. From DailyKos and All Things Interesting.....

Man takes a knee during Trump’s stand for the National Anthem celebration

I haven’t found any other information about who this “patriot” is or why he did it.

Brave man.

Credit Carina Bergfeldt SVT

H/T to MTmofo

Update: According to Jesper Zølck of TV 2 Denmark, the gentleman wanted to remain anonymous and didn’t want to say anything.

Jesper took the picture below.

Credit Jesper Zølck, TV 2 Denmark

Learn more about the tragic story of August Landmesser, the man who refused to salute Hitler.

Source: Blogspot

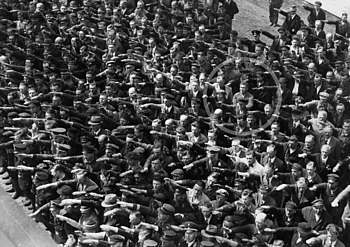

The photo above has floated around the internet for a few years now, popular for one of its subjects’ subtle yet profound acts of nonconformity. There is no telling how many men in that crowd were acting out of fear, fully aware that failing to salute the Fuhrer was akin to signing his own death certificate.

Knowing that it was, in fact, Hitler standing before the crowd makes the disobedience all the more admirable, but what may seem like an act of justified transgression was at its core a gesture of love. August Landmesser, the man with his arms crossed, was married to a Jewish woman.

Source: I Giorni E Le Notti

The story of August Landmesser’s anti-gesture begins, ironically enough, with the Nazi Party. In 1930, Germany’s economy was in shambles, and the unstable nature of the Reichstag eventually led to its demise and ultimately the rise of the opportunistic leadership of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party.

Believing that having the right connections would help land him a job in the pulseless economy, Landmesser became a card-carrying Nazi. Little did he know that his heart would soon ruin any progress that his superficial political affiliation might have made.

Source: Mental Floss

In 1934, Landmesser met Irma Eckler, a Jewish woman, and the two fell deeply in love. Their engagement a year later got him expelled from the party, and their marriage application was denied under the newly enacted Nuremberg Laws.

They had a baby girl, Ingrid, in October of the same year, and two years later in 1937, the family made a failed attempt to flee to Denmark where they were apprehended at the border. August was arrested and charged for “dishonoring the race,” and briefly imprisoned.

Source: Mental Floss

In court, the two claimed to be unaware of Eckler’s Jewish status as she had been baptized in a Protestant church after her mother remarried. In May 1938, August was acquitted for lack of evidence, but with a severe warning that punishment would follow if Landmesser dared repeat the offense.

Officials made “good” on their word, as only a month later August would be arrested again and sentenced to hard labor for thirty months in a concentration camp. He would never see his beloved wife again.

Source: Movimiento Humanista

Meanwhile, a law was quietly passed that required the arrest of Jewish wives in the case of a man “dishonoring the race,” and Irma was snatched up by the Gestapo and sent to various prisons and concentration camps, where she would eventually give birth to Irene, Landmesser and Eckler’s second child.

Both children were initially sent to an orphanage, though Ingrid, spared a worse fate for her status as “half cast,” was sent to live with her Aryan grandparents. Irene, however, would eventually be plucked from the orphanage and sent to the camps, were a family acquaintance not to have grabbed her and whisked her away to Austria for safekeeping.

Upon Irene’s return to Germany, she would be hidden again–this time in a hospital ward where her Jewish identification card would be “lost,” allowing her to live under the noses of her oppressors until their defeat.

Source: Mental Floss

Their mother’s tale is much more tragic. As her daughters were being bounced from orphanages to foster homes to hiding places, Irma ultimately met her maker in 1942 in the gas chambers at Bernburg.

August would be released in 1941 and began work as a foreman. Two years later, as the German army became increasingly mired by its desperate circumstances, Landmesser would be drafted into a penal infantry along with thousands of other men. He would go missing in Croatia where it is presumed he died, six months before Germany would officially surrender.

Source: Senri No Michi

The now-famous photograph was probably taken on June 13th 1936, when August Landmesser was working at the Blohm + Voss shipyard and still had a family to return to at the day’s end. During the unveiling of the new Horst Vessel, workers were stunned to see the Fuhrer himself in front of the ship.

August Landmesser likely found himself incapable of saluting the very man who publicly dehumanized his wife and daughter, and scores of others just like them, only to go home and embrace them several hours later. Landmesser might have been casually aware of propaganda photographers in the shipyard, but in that moment, his only thought was of his family.

August and Irma were officially declared dead in 1949. In 1951, the Senate of Hamburg recognized the marriage of August Landmesser and Irma Eckler. Their daughters split their parent’s names, Ingrid taking their father’s and Irene keeping their mother’s.

Next, see what “normal” life was like during Nazi Germany. Then read about the notorious “Bitch of Buchenwald.”

August Landmesser

August Landmesser (born 24 May 1910;[1] KIA 17 October 1944; confirmed in 1949) was a worker at the Blohm+Vossshipyard in Hamburg, Germany, best known for his appearance, according to the claim of his daughter, disputed, in a photograph[2] refusing to perform the Nazi salute at the launch of the naval training vessel Horst Wessel on June 13, 1936.[3] He had run afoul of the Nazi Party over his unlawful relationship with Irma Eckler, a Jewish woman. He was later imprisoned and eventually drafted into penal military service, where he was killed in action; Eckler was sent to a concentration camp where it is presumed she was killed.

Biography[edit]

August Landmesser was the only child of August Franz Landmesser and Wilhelmine Magdalene (née Schmidtpott). In 1931, hoping it would help him get a job, he joined the Nazi Party. In 1935, when he became engaged to Irma Eckler (a Jewish woman), he was expelled from the party.[4] They registered to be married in Hamburg, but the Nuremberg Lawsenacted a month later prevented it. On 29 October 1935, Landmesser and Eckler's first daughter, Ingrid, was born.[4]

A now-famous photograph, in which a man identified as Landmesser refuses to give the Nazi salute, was taken on 13 June 1936.[5]

In 1937, Landmesser and Eckler tried to flee to Denmark but were apprehended. She was again pregnant, and he was charged and found guilty in July 1937 of "dishonoring the race" under Nazi racial laws. He argued that neither he nor Eckler knew that she was fully Jewish, and was acquitted on 27 May 1938 for lack of evidence, with the warning that a repeat offense would result in a multi-year prison sentence. The couple publicly continued their relationship, and on 15 July 1938 he was arrested again and sentenced to two and a half years in the Börgermoor concentration camp.

Eckler was detained by the Gestapo and held at the prison Fuhlsbüttel, where she gave birth to a second daughter, Irene.[5] From there she was sent to the Oranienburg concentration camp, the Lichtenburg concentration camp for women, and then the women's concentration camp at Ravensbrück. A few letters came from Irma Eckler until January 1942. It is believed that she was taken to the Bernburg Euthanasia Centre in February 1942, where she was among the 14,000 killed; in the course of post-war documentation, in 1949 she was pronounced legally dead, with a date of 28 April 1942.

Meanwhile, Landmesser was discharged from prison on 19 January 1941.[4] He worked as a foreman for the haulage company Püst. The company had a branch at the Heinkel-Werke (factory) in Warnemünde.[6] In February 1944 he was drafted into a penal battalion, the 999th Fort Infantry Battalion. He was declared killed in action, after being killed during fighting in Croatia on 17 October 1944.[7] Like Eckler, he was legally declared dead in 1949.[7]

Their children were initially taken to the city orphanage. Ingrid was later allowed to live with her maternal grandmother while Irene went to the home of foster parents in 1941. Ingrid was also placed with foster parents after her grandmother's death in 1953.

The marriage of August Landmesser and Irma Eckler was recognized retroactively by the Senate of Hamburg in the summer of 1951, and in the autumn of that year Ingrid assumed the surname Landmesser. Irene continued to use the surname Eckler.

Recognition[edit]

In 1996, Irene Eckler published the book Die Vormundschaftsakte 1935–1958: Verfolgung einer Familie wegen "Rassenschande" (The Guardianship Documents 1935–1958: Persecution of a Family for "Racial Disgrace"). The book tells the story of her family, and includes a large number of original documents from the time in question, including letters from her mother and documents from state institutions.[5]

A figure identified by Irene Eckler as August Landmesser is featured in a photograph taken on 13 June 1936, published on 22 March 1991 in Die Zeit. It shows a large gathering of workers at the Blohm+Voss shipyard in Hamburg, for the launching of the navy training ship Horst Wessel. Almost everyone in the image has raised his arm in the Nazi salute, with the most obvious exception of a man toward the back of the crowd, who grimly stands with his arms crossed over his chest. Several others have also refrained from saluting, but are not so obviously defiant.

Whether the depicted man is Landmesser is not known with certainty. Another family claims the person in the photo is another metalworker at Blohm & Voss, a man called Gustav Wegert.[8]

The content and photos posted by relatives of Wegert[9] and more recent photographic enhancements make it more likely that the person in the photo refusing to perform the Nazi salute was Gustav Wegert.[10][dubious ]

References[edit]

- ^ Eckler, Irene (1996). Die Vormundschaftsakte 1935-1958: Verfolgung einer Familie wegen "Rassenschande": Dokumente und Berichte aus Hamburg. Horneburg. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Straße, Amanda. "Verbotene Liebe | Courage". Fasena.de. 1&1 Internet. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Simone Erpel: Zivilcourage : Schlüsselbild einer unvollendeten „Volksgemeinschaft". In: Gerhard Paul (Hrsg.): Das Jahrhundert der Bilder, Bd. 1: 1900–1949, Göttingen 2009, pp. 490–497, ISBN 978-3-89331-949-7.

- ^ a b c Roux, François. Comprendre Hitler et les allemands. Paris, France: Éditions Max Milo. ISBN 9782315004614. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ a b c Flock, Elizabeth (7 February 2012). "August Landmesser, shipyard worker in Hamburg, refused to perform Nazi salute (photo)". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C.: Washington Post Media. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Straße, Amanda. "Father reported missing". Fasena.de. 1&1 Internet. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ a b Bartrop, Paul R. (2016). Resisting the Holocaust: Upstanders, Partisans, and Survivors. ABC-CLIO. p. 152.

- ^ Gerhard Paul, Das Jahrhundert der Bilder 1900 bis 1949, Verlag Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2009, Seite 494 rechte Spalte Absatz 3), as quoted in [1]. Quote: „In the meantime another Family from Hamburg has identified the man as a relative. It should be Gustav Wegert (1890-1959) who worked as a metalworker at Blohm & Voss. As a believing Christian he generally refused the Nazi Salute. Despite his distance to the Nazi Regime Gustav Wegert did not get in the eye of the Nazi persecution administration. Portraits from Wegert and Landmesser prove in both cases great similarity with the worker on that picture. At this time it has to remain unsettled who the man in the picture is“.

- ^ http://wegert-familie.de/home/English.html

- ^ http://www.strangehistory.net/2014/10/26/german-non-saluter-myth/

No comments:

Post a Comment