5 min 41 sec Click the link to listen to the story http://www.npr.org/player/v2/mediaPlayer.html?action=1&t=1&islist=false&id=230965782&m=231250051

The wreckage of an American helicopter sits

in Mogadishu, Somalia on Oct. 14, 1993. The events of the Battle of

Mogadishu became a flashpoint for conversations about military

interventions — and fodder for a big-budget Hollywood drama.

Revisiting Black Hawk Down

Brown's first selection is a Daniel Klaidman piece from The Daily Beast today, looking at a fateful U.S. military operation in Somalia from the vantage point of 20 years later. Eighteen American soldiers were killed in the Battle of Mogadishu when a rescue mission — one that was later dramatized in the Ridley Scott film Black Hawk Down — went terribly wrong.

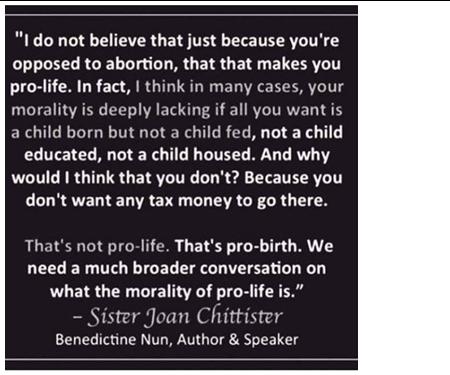

"Of course it's now become a kind of mantra, that we don't want to have 'another Black Hawk Down' ... when people talk about intervention or going into a very risky place to rescue people."

In "," Klaidman interviews many of the people who were part of the mission, drawing somewhat different conclusions than were arrived at in the movie inspired by the incident.

"The mantra of that movie, at the end, was 'It's not about politics, it's not about a mission, in the end it's about the man standing next to you,'" Brown says. "He's the guy that you fight for, he's the guy that you die for.

"But 20 years later, when Dan Klaidman goes back to interview many of the people who were part of it, it's more complicated than that. Yes, it was about their colleagues. But they do also want questions answered."

"They really want to know whether this was worth it," Brown continues. "Why [it was] that people died. Why we were there at all. And was this mission in vain? It's a very haunting thing for the people who lived and survived."

The article also looks at how the operation has affected the lives of the soldiers who were there.

The remains of a U.S. soldier killed in Afghanistan in May arrive at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware. In Breach of Trust,

writer and veteran Andrew Bacevich asks whether we the people are

sufficiently connected to those who fight our wars — and die in them.

The Heroes Of The Military

"The whole question now is whether or not we have now become far too dislocated from the ethos, from the values and from the sacrifice of our military," Brown says, talking about her second selection. It's Breach of Trust, a book by Andrew Bacevich about the public's relationship with the military.

"He himself is a vet and his son died Iraq. And he talks about how we all stand up and have patriotic moments at the start of ball games — we all sort of salute and say thank you for your service — but then we really move on," she says. "There's a great disengagement now. We are disconnected from our military. It is they who go make the sacrifice, and we simply say 'thank you for your service' and go shopping."

The book also looks at how this disconnect may have changed how and when we go to war.

"[Bacevich] thinks that this dislocation between civilian life and military life has allowed our military leaders far too long a rope to send us into reckless wars," Brown says. "That if, in fact, there was far more engagement, we wouldn't have had more than a decade of unwinnable wars. Had we been sacrificing, we would have probably ended these wars way, way faster than they did."

When Heroism Means Saying 'No'

Brown's final pick is yet another Daily Beast article, this time reported by Andrew Slater.

A Syrian soldier takes aim at rebel fighters positioned in the mountains of the town of Maalula in September.

"It talks about how heroism really can also be simply about saying 'No,'" Brown says. "[The soldier] was given the instruction to shoot a group of 30 men coming out of a mosque, and when the order came to fire, he told the five guys with him to shoot over them, not at them."

The five soldiers were arrested for not following orders.

"They were tortured in prison for three days," Brown says. "And one of them eventually confessed that it was our hero who had told them not to shoot" — and then he was arrested.

Finally, a lawyer for one of the five soldiers helped to get him released, after which he fled to Iraq.

"What it shows, I think, is that just by saying 'No' you can be a hero," Brown says. "Here is a guy who is willing to go through torture, beatings, humiliation and terror, simply because he knew it was the wrong thing to shoot people that he'd been told to shoot. He refused to follow orders, he's an unsung hero and I'm so thrilled, in a way, that we've given him his voice with this piece."

http://www.npr.org/2013/10/10/230965782/tina-browns-must-reads-on-heroism

Twenty

years later, the battle still echoes in America’s top policy circles.

As the U.S. sets foot in Somalia again, men who fought in 1993 tell

Daniel Klaidman what still haunts them.

Danny

McKnight’s trip began in a tiny New England cemetery on Saturday,

September 28, 2013—a crisp, clear fall morning. He kneeled by the

gravestone of Corporal James Cavaco and placed a rock on top of it.

McKnight’s wife, Linda, had painted the rock black, and on it, he had

written with a silver Sharpie, “An American Hero” and “RLTW”—Rangers

Lead the Way, the elite infantry unit’s motto.

A

child walks near the wreckage of an American helicopter in Mogadishu,

Somalia on October 14, 1993. (Scott Peterson/Liaison, via Getty)

McKnight

was at the outset of a pilgrimage to the gravesites of men who served

under him in Somalia—his “kids,” as he calls them. They were part of

Task Force Ranger, an American assault team assigned to capture Mohammad

Farrah Aidid, an elusive Somali clan leader who held sway over the

war-torn city of Mogadishu. On October 3, 1993, the team began what

seemed at first to be a routine mission to detain two of Aidid’s top

advisers. But after a Black Hawk helicopter was shot down, the operation

shifted to a far more dangerous rescue mission—what would become the

bloodiest U.S. combat engagement since the Vietnam war.

Cpl. Cavaco, “Vaco” to his friends, was a gunner in a convoy that McKnight led through the dusty, blood-stained streets of Mogadishu that day. Known for his devastating accuracy, Cavaco fired round after round into a second-story window from which the convoy was taking fire. But on the streets of “Mog,” Somali bullets and RPGs seemed to be coming from every direction at a terrifying volume. He was hit by a bullet in the back of the head and died instantly. In the end, the 18-hour fight left 18 American soldiers and airmen dead, and 73 wounded. As many as 1,000 Somalis were killed, by some estimates.

Today, thanks to Mark Bowden’s best-selling book Black Hawk Down, and a blockbuster movie of the same name, the battle is one of the best-known episodes in American military history. And like many pivotal historical events, it has, over time, acquired a number of meanings. To the public at large, the episode became synonymous with raw, almost inconceivably selfless battlefield bravery. The movie, coming right after 9/11, when Americans were rallying around their armed forces, was itself a cultural moment.

In the policy arena, the incident left a profound imprint on a generation of national security decision makers, making them skittish about sending small groups of soldiers into chaotic situations. “It was the policy equivalent of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder,” a recently retired U.S. general told me. (Just this past weekend, Navy Seals staged a daring raid on the seaside villa of a senior Islamist leader in Somalia. Yet the fact that the American Commandos retreated under fire without capturing their target—to avoid civilian casualties, officials say—suggests there is still trepidation about the possibility of another Black Hawk Down.)

For those who fought there, the legacy of Black Hawk Down is more complicated. Partly, it’s about the loss of their comrades and the traumatic experience of combat; it’s also about the pride of having faced the most extreme of human tests, and measuring up. Yet for many combatants, the battle’s legacy is about bigger questions as well. Had their friends died in vain? How could future Black Hawk Downs be prevented? And who gets to control the lessons of what happened on the battlefield?

----

McKnight was a stoic presence for his troops, a seemingly fearless leader who pushed through the fire zone as if oblivious to danger. But he was crushed by the deaths of the six soldiers who served under his command. Later, he vowed that every five years he would visit their graves and spend time with their families.

After visiting Cavaco’s grave, he next traveled to the Sacred Heart Cemetery in Vineland, New Jersey, where he paid tribute to Dominick Pilla, beloved by his teammates for his Jersey sense of humor and the satirical skits he put on at the expense of their commanding officers. Pilla, like Cavaco, was a gunner; he too was shot in the head and killed early in the battle.

On Monday morning September 30, McKnight visited Arlington National Cemetery, where Sgt. Casey Joyce and Specialist Richard Kowalewski are laid to rest. The burial ground was empty except for the occasional horse-drawn caisson being pulled through its quiet lanes.

Along the way, McKnight spent time with the families, keeping alive the memories of their loved ones by telling stories. But there were also moments of personal soul searching—the resurfacing of questions that never fully go away. After the chopper went down, McKnight was redirected to the crash site where much of the fighting force was pinned down. Massive enemy fire, road blocks, and poor communications hampered his ability to reach them. Faced with the choice of trying to grind ahead toward the crash zone with a convoy full of prisoners and bloodied soldiers or return to the base, McKnight decided to return home. He calls it the toughest decision of his life.

At Fort Benning, Georgia he visited the gravesite of Corporal Jamie Smith, who had been shot in the thigh while closing in on the crash site. The bullet severed one of Smith’s femoral arteries and he bled to death several hours later. Even though doctors told McKnight that he’d never have been able to save Smith, he is still haunted by the memory. “If I could have gotten that convoy there that day, he would be here,” McKnight told me.

Following a trip to Fort Bliss in El Paso—where he visited the grave of Sgt. Lorenzo Ruiz—McKnight ended his pilgrimage on October 3 in north Texas, the site of one of several Black Hawk Down reunions taking place around the country for the battle’s 20th anniversary.

A

crowd of Somalis cheer in Mogadishu as the body of a U.S. soldier is

dragged through the streets on October 4, 1993. (AFP/Getty)

The

reunion weekend began at a VFW hall in a non-descript strip mall in

Plano—the Casey Joyce All-America Post 4380. (Joyce was a Plano native.)

When I arrived, around 5:00 pm, the room was thick with cigarette smoke

and country rock music blared over the speakers. Veterans of old and

more recent wars crowded around the bar downing shots of Regal Crown

Black, chased by Shiner Bock.

A couple of vets of Task Force Ranger were already there, but around 6:00, more began filtering in—eventually numbering a few dozen. As they saw each other, in some cases for the first time since they’d left Somalia, their eyes lit up. They exchanged long hugs, kidded each other, teasingly pulled rank, and shouted “hooah,” the warrior expression of approval.

The weekend was filled with poignant moments, like when Mike Kurth told Sean Watson about an act of leadership he’d always admired but never acknowledged. When word reached the Rangers at the crash site that the convoy was headed back to base and would not be able to pick them up, Kurth’s instinctive reaction was, “We’re fucked!” But it was Watson who understood the need to sustain the morale of the troops. “We could be here for a little while,” he said calmly. “Everyone needs to preserve their ammo.”

There were bittersweet moments, too. One was when the widow of Casey Joyce embraced Todd Blackburn, the private who’d missed his rope as he leapt from the helicopter and fell 70 feet to the ground at the outset of the operation. It was Joyce who’d scurried for a medevac vehicle, an intrepid act that may well have saved Blackburn’s life. A few minutes later, Joyce was killed, shot in the back by a Somali militiaman.

The psychological after-effects of battle are, of course, very different from soldier to soldier. One Ranger I spoke with, Christopher Atwater, seemed troubled by the fact that he didn’t know the answer to a question he’s been repeatedly asked over the years: had he killed anybody? “I don’t know,” he said, narrowing his eyes. “I fired my weapon and I did the best job I could.” The wife of another Ranger said her husband hadn’t sought much counseling after Mogadishu but early October is usually a difficult time for him. “He gets real withdrawn,” she said.

Among the anxieties experienced by Black Hawk Down veterans is a sense that their stories might be forgotten. Andrew Flores, a member of the 10th Mountain Division, part of the quick reaction force that was brought in late to the battle to mount an armored rescue, lamented that his fellow Mountaineers were overshadowed by the Rangers, Delta Force, and other elite operators depicted in Bowden’s book. Pulling me away from the crowd at the VFW, Flores said, “We suffered, we lost men, we bled that day.” (Two members of his division died in the battle.) And he pleaded that we not forget their sacrifice. “Don’t let ours be another forgotten war.”

Mike Kurth retired in 1996, but after the attacks of 9/11 he had a powerful urge to reenlist. By then in his 30s, he felt he still had something to contribute. But in retrospect he also thinks the impulse may have stemmed from survivor’s guilt. He sought some counseling, talked to some of his Ranger buddies, and eventually concluded, “It’s ok to be happy.”

Kurth was hardly alone in finding a way to move on: Bowden says most of the men emerged from Black Hawk Down emotionally and psychologically intact. They were proud to have served in a fight that will stand in the pantheon of American battles for its acts of valor and sacrifice. “If they believed in what they were doing and they acquitted themselves well and didn’t betray their cause, then they came out of it well,” Bowden says. “Some come out of combat deeply troubled and wounded,” he adds. “But most don’t.”

----

The U.S. involvement in Somalia began in 1992 as a humanitarian operation aimed at ending a devastating famine. These were heady days for America. The Cold War had recently ended and the country’s sense of hegemony was only heightened by its crushing defeat of Saddam Hussein’s army in the first Gulf War. The Somalia intervention was an expression of what George H.W. Bush dubbed “The New World Order”: the United States, the world’s remaining superpower, would be in the vanguard of a muscular multilateralism that would seek to prevent humanitarian catastrophes and human rights abuses.

But following Black Hawk Down, it became clear that international altruism could be costly. The Clinton White House, under heavy congressional pressure, pulled out of Somalia, and the episode spawned a whole new lexicon for policymakers spooked by the prospect of the United States getting ensnared in future military debacles. It was during the Somalia operation that a Washington Post columnist coined the term “mission creep” to characterize ill-defined ventures that could easily spin out of control. Meanwhile, “we don’t want another Black Hawk Down” became a reflexive catchphrase for policymakers wary of American intervention.

Just days after Clinton called off Task Force Ranger’s mission in Somalia, a U.S. Navy vessel anchored in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. U.S. and Canadian peacekeepers were deploying to train Haitian security forces for the return of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. But when the U.S.S. Harlan County was greeted by a throng of angry anti-Aristide protestors—some of whom fired shots in the air while others shouted “Somalia! Aidid!”—the ship weighed anchor and steamed out of port. A few months later, Clinton chose not to intervene in Rwanda where hundreds of thousands of Tutsis were being slaughtered by rival Hutus. His decision came after Hutu militia members killed and mutilated 10 Belgian U.N. peacekeepers in an echo of what Aidid’s forces had done in Somalia.

Throughout the 1990s, a profound risk aversion settled over civilian policymakers and, to a lesser extent, the military. When the U.S. did intervene militarily, such as in the Balkans, air power was the only real approach considered palatable. “No boots on the ground” became the mantra—a very different American way of war. Some have argued that the Bush administration’s aggressive response to 9/11 laid to rest the ghosts of Black Hawk Down, heralding a new dawn for America’s lethal Special Operations Forces. But even as the Bush administration launched major ground wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, it was still true that there was a deep reluctance to order commando operations in chaotic, out-of-the-way places.

One former top special operations commander recalls what transpired when a mission would be proposed that was “stealthy, surgical, and light,” the bread and butter of special ops: “We’d start with a recommendation of 50 men, but by the time it got briefed all the way up the chain, it would involve 10,000 men” and massive amounts of equipment and armor. Everyone wanted to make sure they’d be able to fight their way out of a Black Hawk Down situation. But then the plan would be cancelled because the Pentagon didn’t want to expend that level of resources.

During his first term, Obama repeatedly resisted putting “boots on the ground” in Somalia and personally invoked Black Hawk Down on more than one occasion, according to one of his closest military advisers. In September 2009, Obama and his advisers debated options for going after Saleh Ali Saleh Nabhan, a top Al Qaeda operative whom U.S. intelligence had identified in Somalia. The military wanted to capture him, but that would have required a potentially risky ground operation. Obama opted for a targeted killing, in which Little Bird attack helicopters strafed his car while he was traveling on an isolated road.

He did allow commandos to touch down in order to collect DNA samples so the military could prove Nabhan had died. But for most of the first term, Obama generally resisted the military’s requests to allow special operations forces to land on the ground—denying them, for instance, the ability to collect a target’s “pocket litter,” valuable intelligence they would likely find on his body or vehicle after the kill.

----

But what about those who fought in Black Hawk Down? On the surface it might appear that, for them, all these policy implications are very much beside the point. It’s an ancient warrior creed that the human experience of combat transcends politics. That attitude is typified by Hoot, the composite character played by Eric Bana in Ridley Scott’s movie version of the battle. “You know what I think,” he says when asked if it was a worthwhile mission. “Don’t really matter what I think. Once that first bullet goes past your head, politics and all that shit just goes right out the window.” Toward the end of the movie, Hoot reduces war to its most elemental quality: “It’s about the men next to you, and that’s it. That’s all it is.”

But that’s not exactly right. The warriors who fought in Mogadishu in some ways care about the politics in a more profound and visceral way than anyone else. If the most emotionally searing experience in combat is the death of a comrade in arms, then the most human impulse of the warrior is to ask: why? For all their expressions of pride in how they fought, some members of Task Force Ranger still are tormented by the belief that their brothers died in vain. They point to President Clinton’s decision to call off the mission after October 4, even though the objective of capturing Aidid had not been achieved.

“We had 18 lives committed to that mission,” says retired Col. Thomas Matthews, the air mission commander who guided the pilots of the 160th Nightstalkers in Mogadishu. “Once they decided to commit us, they needed to let us finish the job.”

Nothing seems to stir more ire than the fact that a few weeks after the battle, the Clinton administration entered into negotiations with Aidid, transporting him on a U.S. plane. Some members of Task Force Ranger were even assigned to provide security for the negotiations. “Don’t ask us to guard him,” says Mike Kurth, his lip quivering with anger at the thought of it all these years later.

Kurth and most of the veterans of Task Force Ranger are in no way trapped by Black Hawk Down. Still, many of the paths they’ve chosen have kept them connected to that formative experience. A number of them, like McKnight and Matt Eversmann—the Ranger played by Josh Hartnett in the movie—became motivational and public speakers, drawing on the experience to impart lessons about leadership and sacrifice and commitment.

Some Task Force Ranger vets left the military relatively soon after Black Hawk Down. William F. Garrison, the general who commanded the operation and was played by Sam Shepherd in the film, took full responsibility for the episode’s tactical failings. Shortly after the event, he hand-wrote a letter to President Clinton, Defense Secretary Les Aspin, and members of Congress explaining his actions but not making any excuses. His career was short-circuited and he retired two years later.

Garrison now lives on a farm in Hico, Texas, and has never given an interview about Black Hawk Down. He is revered by most of the troops who served under him in Somalia. During the reunion weekend, he attended a barbeque held at Ross Perot’s house in Texas. He apparently mingled easily with the members of Task Force Ranger and seemed happy to be there.

Many others who participated in Black Hawk Down stayed in the military and are just beginning to retire now. Eversmann, who served a 15-month tour in Iraq and retired in 2008, says that, before deployment, he obsessively tried to meet as many of the family members of the soldiers who served under him as he could. He never again wanted to have to meet them for the first time at their child’s funeral, as he had after Black Hawk Down.

A number rose thorough the ranks to become senior commanders in Iraq and Afghanistan. Captain Mike Steele was a company commander whose Ranger and Delta operators provided security around the crash site of one of the downed Black Hawks. They fought off thousands of militants throughout the night, but several of Steele’s men were killed. Later, according to a profile in The New Yorker, Steele was haunted by questions about whether his troops had been adequately prepared for the battle. The story suggested he would never let that happen again. As a result, some allege that in Iraq he created a culture of aggressive soldiering—one that may have gone too far. He was investigated for his role in the killing, by soldiers under his command, of four unarmed Iraqis. Though Steele was never charged, he was given a career-ending reprimand.

Chris Faris, a Delta Force operator in Mogadishu, rose to the pinnacle of the military’s elite forces. He is Command Sergeant Major to the Special Operations Command and, thus, the top enlisted adviser to Admiral William McRaven. In Somalia, Faris was part of the initial Delta assault team assigned to capture Aidid’s aides. After the first Black Hawk went down, Faris and his team moved toward the helicopter to secure the crash site.

On the way, they encountered a ferocious ambush. Earl Fillmore, a Delta operator two or three men up from Faris, took a round in the head, or, as Faris puts it, was “drilled in his brain housing group.” Seconds later, a soldier standing directly in front of him was shot. As Faris tended to his wound, he was shot in the back. The bullet didn’t penetrate his armor, but the kinetic force of the round caused hydrostatic shock and some internal bleeding. He was able to function, but he believed he was going to die. In a house the team had occupied, Faris held up his wedding band and said goodbye to his wife and his two small daughters. By now a calm had settled over him, a kind of primordial survival instinct, he believes. The only thing he feared was that if he died, his family would see his mutilated corpse dragged through the streets.

Faris survived and went on to have a storied career in America’s shadow wars, participating in or supervising thousands of classified missions in the world’s most dangerous places. Still, all these years later, Faris says there isn’t a day that Black Hawk Down doesn’t flash through his mind.

For him, the legacy of the mission is complicated. He appears troubled by those who weren’t there yet seem to have appropriated the legacy of the battle for their own political purposes. In 2009, he was part of a Pentagon team that proposed a secret counterterrorism mission in Somalia. At a planning session with senior Obama aides, a high-ranking State Department official said he was uncomfortable with the plan because he was worried it would lead to “another Black Hawk Down.” According to Faris, the official went on to say, “I’m the guy who had to fly into Mogadishu afterwards to clean up your mess.” (The official apparently did not know that Faris had been in Mogadishu.)

Faris began to sense the anger rising up through his body. As he started to get up, he felt Admiral McRaven’s hand squeezing his thigh. He got the message and sat back down. But he still boils when he thinks about it. What would he have told him, I asked Faris? “This guy didn’t know that when Earl Fillmore was killed his blood and brains were seeping out of his helmet,” says Faris. “Or that five hours later, moving his cold body to another position, rigor mortis has set in and his arms are sticking straight up into the air. He doesn’t know what a mess is.”

At the same time, Faris also knows that there are political lessons to be learned from Black Hawk Down: he speaks with conviction about never sending people into battle without a clear, attainable objective and without fully considering the consequences of those actions, something he says was not done before the battle in Mogadishu. “I thought the larger mission was bullshit,” he says. “Everyone died for absolutely no reason. It was wasted lives, wasted blood, and wasted treasure, and I’m angry about it.” Faris says that he vowed as a commander that he would never send a man or woman into battle unless he could tell their mother or father that their child did not die in vain.

In the end, the human toll of war cannot be separated from the larger political questions. They are intertwined and co-dependent. There was enormous heroism, valor, and tragedy in Mogadishu. “But,” says Andrew Bacevich, a professor at Boston University and retired Army colonel, “if you reduce war simply to a human story, you rob it of its political significance.”

“And war,” adds Bacevich, who lost a son in Iraq, “is ultimately a political act that has to be judged on that basis.” Many veterans of Task Force Ranger intuitively seem to understand that.

http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/10/09/black-hawk-down-s-long-shadow.html

Syrian government forces patrol the Khalidiyah neighborhood in the central city of Homs on July 28, 2013. (AFP/Getty)

In

the coming days the United States and other countries will make a

decision on the use of military force against Syria. The consequences of

this decision will affect not only the Assad regime loyalists but also

the foot soldiers manning bunkers, barracks, and installations across

the country. For the vast majority of Syria’s conscripted soldiers,

military service amounts to a brutal prison sentence of unknown length

now that the war has extended service periods indefinitely. Though the

Syrian army does contain true believers who believe that it’s their duty

to defeat the rebels and any means justifies this end, many are

draftees with no ideological sympathy for the regime and are merely

following orders to survive.

Faced with certain death for desertion, and possible retaliation against their families, many conscripts have been put in the nightmarish situation of choosing between committing war crimes or being killed for trying to flee from a war effort they don’t support.

The excuse of “following orders” has its moral limits but to ignore the position forced on Syrian conscripts is its own form of blindness. Pretending that all Syrian soldiers are the same and equally culpable may be of some comfort if the decision to attack is made but it obscures the truth of the situation.

Most deserters living in refugee camps are now scarred by the brutality they witnessed and participated in, all for a cause they despised. There is no one to sympathize for their war trauma and most would like nothing more than to forget. You won’t hear from the unsuccessful deserters and dissenters of the Syrian ranks who have been executed anonymously, often casually by a loyal inner corps of junior officers and paramilitary, in untold thousands.

What follows is the first-person account of a former Syrian Army sergeant who was imprisoned for protesting orders to shoot civilians. I interviewed the man, whose name and identifying details I have altered to protect his identity, in late 2012 at a refugee camp in Northern Iraq. The interview, which has been edited for length and to preserve the voice of “Heen,” is a testimony to the evolution of events in Syria. In this first part, Heen describes his unit’s role in Dara’a, where the protests started and the war began and concludes with the events that led to his own arrest. Click here to read the second installment, in which Heen describes being imprisoned and fleeing Syria for a refugee camp in Iraq.

No one thought anything like this could ever happen in Syria. When I reported for my conscription in 2010 I thought I would do my two years of service without anything happening. Everyone said it would be bad, that they would insult you and hit you, but you could put up with it. I didn’t think I would ever see a war. Before the war I was a short-order cook in Zabadani, which is a beautiful tourist valley in Reef Damashq, near Lebanon. All kinds of foreigners came there for vacation, Khaleejis [Gulf country citizens], Lebanese, even Europeans. The mountains are very beautiful there.

After six months’ basic training in Khan Ash Shaykh, I was made a sergeant in charge of a BMP [a Russian-made armored personnel carrier] section. I was in charge of 14 privates in my unit, almost all young Sunni Arab guys. Kurds like me usually don’t get made sergeant. There were 16 sections like mine in my company with a captain in charge. There were no lieutenants in our unit, just musa’ada, or warrant officers, to help the captain.

Our captain had a very strong voice and a strong personality; he was an Alawi like most officers. He never sounded unsure of himself or conflicted about what we had to do in Dara’a. While he got his orders from the ameed, the colonel, mostly he had freedom to do anything he wanted in our assigned area: arrests, raids, shootings, destroying buildings.

Our unit was sent to Dara’a after the protests started in March of 2011 and our area was at the center of the problems because it contained the Umari mosque. There was no base for us in Dara’a so we took over an elementary school and turned it into our base. At the beginning we never worried about being attacked, we just had to deal with protests. We thought we would be there for a few weeks and then things would settle down.

When we arrived in Dara’a we were given strict orders to never speak with civilians there. Not during arrests, not breaking up protests, not on patrols. You would be beaten and sent to jail if you were seen speaking at length with civilians. We were told repeatedly that the protests were instigated by infiltrating foreigners, mostly supported by the U.S. and Western powers to undermine Syria, and that most of the protesters weren’t even Syrian. We were told they were Iranians, Afghanis, Americans, and Pakistanis forming these groups. As time went by it was obvious this wasn’t true and much of it didn’t make sense, but you couldn’t speak openly about it. At first, most of us just accepted that foreigners were behind it all.

In the beginning we were strictly prohibited from shooting at the protesters and the officers were very careful to avoid confrontation. At first we would just show up and surround the protests and hope that the show of force would convince them to disperse. Almost all of the protests started after Friday prayer at the mosques, because that is when all the men in the area gather together. We came to expect that every Friday we would have to break up a protest, but they grew larger and larger. When they became too large for us to arrest and disperse we began firing over the crowd or at unoccupied buildings nearby. When this didn’t work, my captain ordered me to fire a tank shell into a building near the protesters, but we didn’t kill anyone until later in April.

We heard that protesters had been tearing up posters of Assad, I don’t know where, and the colonel flew into a rage. I remember the protest that Friday outside the Umari mosque and at first we fired over the heads of the protesters. Then the colonel arrived at our position and told the captain to have us shoot into the crowd. The captain gave the order and he was the first one to shoot at them with his rifle. It wasn’t a free for all, but my soldiers all shot a burst or two into the crowd and everyone ran. Some shot more than others.

I remember it was a warm and mild day, sunny and clear. Within 10 minutes of the shooting starting, the streets were empty. After a while, people carefully came up to drag the bodies out of the street. I remember seeing the bodies lying in the street. Our chain of command told us that the eight we had killed in the protest had all been foreigners. None of us had hesitated to shoot, because we all believed it. We only realized over time.

Within my section I had a difficult time with my pro-Assad soldiers, my dirty guys. They were Sunni Arab but they came from tribes in Raqqah that were favored by the regime and they were ignorant. Some of them had clips of Assad’s speeches and pro-Assad songs on their phones they would listen to all the time. When we were waiting for protests to emerge, my worst soldier would lean on his machine gun and say, “Hurry up and come out so I can start shooting you.”

Most of my guys were not like this, but you had to act like you supported the government. As we shot at more and more protests and killed more and more civilians, I started to notice there were five other soldiers in my unit who realized that killing the protesters was wrong. Some of them would ask why we were shooting at people, even though in the end they had to do it like everyone else. Maybe there were more, but I knew that these five felt like I did. I told them discreetly that when the order came from the captain to shoot, to shoot near people but don’t hit them, so you seem like you are following orders.

One of my soldiers would shout curse words while he shot into the crowds and seemed to enjoy killing people. I had to be very careful around soldiers like this. We divided our time between living out of our BMP vehicle at an intersection which we were charged with guarding and at the school. All we had was a bed roll and a blanket, but it was very hot during the summer and impossible to sleep during the day. There were sinks and toilets in the school and tents in the courtyard, but we were still miserable.

I rarely got to speak with my parents on the phone, but the conversations were difficult. Everyone knows that the government could be listening, so you have to be very careful about how you talk. They were very worried about me. My father would speak in a coded way that let me know they were worried that I was doing bad things and that I was involved in the horrible things the Army was doing. I tried to reassure them, but after a while I got very angry. I couldn’t tell them about how impossible things were for me here. They didn’t understand what life was like for me and I couldn’t really explain it on the phone.

Officially school ended in July, but students stopped showing up in April, once the siege started. We had set up very strict curfew rules, and since we could not speak with the locals, communications were made by loudspeakers. Only women and children were allowed to leave the home between 5 and 7 in the evening to obtain essential things. To enforce this, people in the street were shot on sight, and Dara’a became a ghost city.

Only one of my soldiers was hurt in the fighting while I was there. One night, we were at a security position outside our BMP vehicle when someone threw a grenade at us from a nearby building. One of my soldiers was hit by fragments, but he lived. Much of the fighting was at night when the resistance could move around without being seen. There was a lot of mortar and RPG fire at us, but it was mostly inaccurate. Because units didn’t talk to each other there were lots of friendly fire incidents at night, 20 soldiers were killed that way while I was there.

When you are a soldier in Syria you must never let anyone think you are religious. You will immediately be suspected of sympathizing with the protesters. No one prays. No one fasts at Ramadan. No one has a Quran or suras from it. No one has tasbeeh prayer beads. You don’t even dare say 'Ya Allah' if you feel emotional about something. Later, when they were beating me in prison and I tried to swear to them, and I said ‘wallah’, they cut me off and said ‘Swear to us. We are your gods here.’

We were encouraged to abuse the people, even when it seemed pointless. We collected 2,000 motorcycles off the street and destroyed them. I ran over many with my BMP. The motorcycles are how poor people get around and live. We stole whatever we wanted from stores as we passed them. My soldiers’ favorite thing to steal was Marlboro cigarettes. One time we were ordered to drive our BMP into the front windows of a supermarket, it was very new and updated, and it collapsed the whole front of the roof. I don’t know why we did it. We were ordered once to shoot the water tanks on top of an apartment building, if you destroy the tank the building gets no water, and my gunner began shooting them all the time after that.

As the situation got worse during the summer, people were too afraid to collect the bodies out of the street. They began to smell very quickly. There was a special unit in charge of collecting bodies who wore black uniforms and drove Toyota trucks belonging to the Amin Al Askari [military security]. We were not supposed to talk to them, but the bodies went to the stadium which had become a makeshift morgue full of freezers.

By August we were rounding up any young man we found, whether we were looking for him or not. At night we would raid houses with the mukhabarat [Syrian intelligence agents], with a big Toyota bus with covered windows to put the prisoners in. The houses were filled with daughters and wives who would scream and cry when we entered. If there were any men, they would either try to run or hide, but we shot runners on sight. The most common hiding places where we found men and boys were under beds, under stairs, and in closets. Almost no one let himself be arrested, because they knew what would happen. They were blind-folded and bound and gathered on our bus to send back to the stadium.

These scenes began to make me crazy. On the buses full of prisoners men were crying and screaming. We had to beat them. I thought about what it would be like if someone raided my parents’ home and dragged me out in front of them. You could not talk about what we were doing ever, but it was clear some believed in what we were doing and others did not.

They arrested me in November. It was a Friday and we saw a group of 30 men come out of a mosque and some of them had pistols. When the order to fire came, I told my five guys I trusted to shoot over them. The captain was there at the time and saw that they were doing this. Later that day, my five soldiers were arrested and taken away. We were not told why. They were tortured in prison for three days and one of them eventually confessed that I had told them not to shoot people. Then they arrested me.

A

Syrian man reacts while standing on the rubble of his house while

others look for survivors and bodies in the Tariq al-Bab district of the

northern city of Aleppo on February 23, 2013. (AFP)

The

following is the second part of an interview conducted with a former

Syrian army sergeant, “Heen,” whose name and identifying details have

been altered to protect his identity. The interview, which has been

edited for length and to preserve the voice of Heen, is a testimony to

the evolution of events in Syria. Click

here to read the first part of the interview where Heen describes his

unit's role in Dara'a, where the protests started and the war began, and

the events that led to his arrest.

In this final part, Heen describes his arrest and imprisonment for disobeying orders to shoot at civilians and his eventual flight to Iraq, where he settled in a refugee camp.

Heen's refugee camp in April 2013. (Nicolas Babonneau )

They

arrested me in November. It was a Friday and we saw a group of 30 men

come out of a mosque and some of them had pistols. When the order to

fire came, I told my five guys I trusted to shoot over them. The captain

was there at the time and saw that they were doing this. Later that

day, my five soldiers were arrested and taken away. We were not told

why. They were tortured in prison for three days, and one of them

eventually confessed that I had told them not to shoot people. Then they

arrested me.

I knew the mukhabarat prison where they took me; I had been there before. I knew exactly what kind of men worked there. It was a squat building with two floors above ground and two below and the grounds surrounded by a wire fence. After my initial beating they brought me into the interrogator’s office blindfolded.

My blindfold was not well secured, so I could see over the top. The interrogator was a heavyset man in a civilian suit, green jacket and pants. From his coastal accent it was clear he was Alawi. He had dyed black hair that was gray at the roots and a thick mustache. There was a television on in the corner with a government station on, Ad Dunia. He did not turn it off for the session. He was very calm when he spoke to me and never got angry.

I spent two months in the basement of the mukhabarat prison. There was only enough room to sit or stand because the cell was so crowded. All of us become covered in lice and insects, which became maddening. It was a mix of military and civilian in the prison. Some soldiers were there for selling military supplies on the black market. Everyone had a single blanket, which was inadequate for the cold of the winter. Eventually, most of us wanted to die rather than continue life there.

The food was half-cooked and revolting. You were given five minutes to eat it. A lot of prisoners began to get sick and there was a man with an open bullet wound that got infected. Some nights I would hear people in other sections screaming like they had gone insane.

Every ten days I was taken up and tortured and interrogated again. These sessions usually lasted five hours. There were no windows or clocks so we had no idea how much time was passing down there.

In January, I was finally transferred to the regular prison at Sayyed Naya under a charge of disobeying orders, cursing the president, and gathering in a group to plan seditious activity. I spent four months at Sayyed Naya, where conditions were slightly better, but not much. There were periodic beatings where the guards would enter with canes. Everyone had to put their hands on the wall and get on their knees, facing the wall. Anyone turning around or not assuming the position would be severely beaten. In this position, they would arbitrarily hit us on the back and head.

I knew I couldn’t go back to my unit, so I contacted a friend who worked in administration to write up a fake leave paper for me. With this fake leave paper I took a collective bus back to Qamashli. There were many checkpoints, but thanks to God the paper worked. I met my uncle near Qamashli, and he knew how to get around the checkpoints to the border with Iraq. The crossing point is called Skoda. He took me there in his pickup truck and dropped me off at Skoda, where I crossed into Iraq on foot, and on the Iraqi side the Peshmerga [the military of the Kurdish Regional Government] were waiting to help us get to the refugee camp. This was June of 2012, and I have been in Iraq ever since.

This interview was conducted with the assistance of a translator, Usama Al-Haddad. Usama is an Iraqi-American currently residing in Erbil, Iraq. He has conducted research at Harvard University, and holds a Masters from the School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London.

Cpl. Cavaco, “Vaco” to his friends, was a gunner in a convoy that McKnight led through the dusty, blood-stained streets of Mogadishu that day. Known for his devastating accuracy, Cavaco fired round after round into a second-story window from which the convoy was taking fire. But on the streets of “Mog,” Somali bullets and RPGs seemed to be coming from every direction at a terrifying volume. He was hit by a bullet in the back of the head and died instantly. In the end, the 18-hour fight left 18 American soldiers and airmen dead, and 73 wounded. As many as 1,000 Somalis were killed, by some estimates.

Today, thanks to Mark Bowden’s best-selling book Black Hawk Down, and a blockbuster movie of the same name, the battle is one of the best-known episodes in American military history. And like many pivotal historical events, it has, over time, acquired a number of meanings. To the public at large, the episode became synonymous with raw, almost inconceivably selfless battlefield bravery. The movie, coming right after 9/11, when Americans were rallying around their armed forces, was itself a cultural moment.

In the policy arena, the incident left a profound imprint on a generation of national security decision makers, making them skittish about sending small groups of soldiers into chaotic situations. “It was the policy equivalent of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder,” a recently retired U.S. general told me. (Just this past weekend, Navy Seals staged a daring raid on the seaside villa of a senior Islamist leader in Somalia. Yet the fact that the American Commandos retreated under fire without capturing their target—to avoid civilian casualties, officials say—suggests there is still trepidation about the possibility of another Black Hawk Down.)

For those who fought there, the legacy of Black Hawk Down is more complicated. Partly, it’s about the loss of their comrades and the traumatic experience of combat; it’s also about the pride of having faced the most extreme of human tests, and measuring up. Yet for many combatants, the battle’s legacy is about bigger questions as well. Had their friends died in vain? How could future Black Hawk Downs be prevented? And who gets to control the lessons of what happened on the battlefield?

----

McKnight was a stoic presence for his troops, a seemingly fearless leader who pushed through the fire zone as if oblivious to danger. But he was crushed by the deaths of the six soldiers who served under his command. Later, he vowed that every five years he would visit their graves and spend time with their families.

After visiting Cavaco’s grave, he next traveled to the Sacred Heart Cemetery in Vineland, New Jersey, where he paid tribute to Dominick Pilla, beloved by his teammates for his Jersey sense of humor and the satirical skits he put on at the expense of their commanding officers. Pilla, like Cavaco, was a gunner; he too was shot in the head and killed early in the battle.

On Monday morning September 30, McKnight visited Arlington National Cemetery, where Sgt. Casey Joyce and Specialist Richard Kowalewski are laid to rest. The burial ground was empty except for the occasional horse-drawn caisson being pulled through its quiet lanes.

Along the way, McKnight spent time with the families, keeping alive the memories of their loved ones by telling stories. But there were also moments of personal soul searching—the resurfacing of questions that never fully go away. After the chopper went down, McKnight was redirected to the crash site where much of the fighting force was pinned down. Massive enemy fire, road blocks, and poor communications hampered his ability to reach them. Faced with the choice of trying to grind ahead toward the crash zone with a convoy full of prisoners and bloodied soldiers or return to the base, McKnight decided to return home. He calls it the toughest decision of his life.

At Fort Benning, Georgia he visited the gravesite of Corporal Jamie Smith, who had been shot in the thigh while closing in on the crash site. The bullet severed one of Smith’s femoral arteries and he bled to death several hours later. Even though doctors told McKnight that he’d never have been able to save Smith, he is still haunted by the memory. “If I could have gotten that convoy there that day, he would be here,” McKnight told me.

Following a trip to Fort Bliss in El Paso—where he visited the grave of Sgt. Lorenzo Ruiz—McKnight ended his pilgrimage on October 3 in north Texas, the site of one of several Black Hawk Down reunions taking place around the country for the battle’s 20th anniversary.

A couple of vets of Task Force Ranger were already there, but around 6:00, more began filtering in—eventually numbering a few dozen. As they saw each other, in some cases for the first time since they’d left Somalia, their eyes lit up. They exchanged long hugs, kidded each other, teasingly pulled rank, and shouted “hooah,” the warrior expression of approval.

The weekend was filled with poignant moments, like when Mike Kurth told Sean Watson about an act of leadership he’d always admired but never acknowledged. When word reached the Rangers at the crash site that the convoy was headed back to base and would not be able to pick them up, Kurth’s instinctive reaction was, “We’re fucked!” But it was Watson who understood the need to sustain the morale of the troops. “We could be here for a little while,” he said calmly. “Everyone needs to preserve their ammo.”

There were bittersweet moments, too. One was when the widow of Casey Joyce embraced Todd Blackburn, the private who’d missed his rope as he leapt from the helicopter and fell 70 feet to the ground at the outset of the operation. It was Joyce who’d scurried for a medevac vehicle, an intrepid act that may well have saved Blackburn’s life. A few minutes later, Joyce was killed, shot in the back by a Somali militiaman.

“It’s about the men next to you, and that’s it. That’s all it is.”Some of the Rangers were staggered by the memories. At the VFW hall on that first night, a short movie was shown about two Rangers who’d recently returned to Mogadishu and drove through the very streets where they had witnessed and taken part in unspeakable carnage. One lanky Ranger, who’d had a few drinks, began to weep as he watched the scenes unfold on the screen. He’d been a cook and not part of the team assigned to go out on the mission. But when a convoy was spontaneously organized to rescue a second Black Hawk pilot who’d been shot down, he as well as others volunteered. Now, two decades later he was crumpled on the ground in front of his former teammates sobbing uncontrollably. His friend, a fellow Ranger cook who’d been on the same rescue convoy, picked him up and wrapped his arms around him. “Maintain yourself,” he told him firmly. Another overwhelmed Ranger watching the movie left the hall and vomited.

The psychological after-effects of battle are, of course, very different from soldier to soldier. One Ranger I spoke with, Christopher Atwater, seemed troubled by the fact that he didn’t know the answer to a question he’s been repeatedly asked over the years: had he killed anybody? “I don’t know,” he said, narrowing his eyes. “I fired my weapon and I did the best job I could.” The wife of another Ranger said her husband hadn’t sought much counseling after Mogadishu but early October is usually a difficult time for him. “He gets real withdrawn,” she said.

Among the anxieties experienced by Black Hawk Down veterans is a sense that their stories might be forgotten. Andrew Flores, a member of the 10th Mountain Division, part of the quick reaction force that was brought in late to the battle to mount an armored rescue, lamented that his fellow Mountaineers were overshadowed by the Rangers, Delta Force, and other elite operators depicted in Bowden’s book. Pulling me away from the crowd at the VFW, Flores said, “We suffered, we lost men, we bled that day.” (Two members of his division died in the battle.) And he pleaded that we not forget their sacrifice. “Don’t let ours be another forgotten war.”

Mike Kurth retired in 1996, but after the attacks of 9/11 he had a powerful urge to reenlist. By then in his 30s, he felt he still had something to contribute. But in retrospect he also thinks the impulse may have stemmed from survivor’s guilt. He sought some counseling, talked to some of his Ranger buddies, and eventually concluded, “It’s ok to be happy.”

Kurth was hardly alone in finding a way to move on: Bowden says most of the men emerged from Black Hawk Down emotionally and psychologically intact. They were proud to have served in a fight that will stand in the pantheon of American battles for its acts of valor and sacrifice. “If they believed in what they were doing and they acquitted themselves well and didn’t betray their cause, then they came out of it well,” Bowden says. “Some come out of combat deeply troubled and wounded,” he adds. “But most don’t.”

----

The U.S. involvement in Somalia began in 1992 as a humanitarian operation aimed at ending a devastating famine. These were heady days for America. The Cold War had recently ended and the country’s sense of hegemony was only heightened by its crushing defeat of Saddam Hussein’s army in the first Gulf War. The Somalia intervention was an expression of what George H.W. Bush dubbed “The New World Order”: the United States, the world’s remaining superpower, would be in the vanguard of a muscular multilateralism that would seek to prevent humanitarian catastrophes and human rights abuses.

But following Black Hawk Down, it became clear that international altruism could be costly. The Clinton White House, under heavy congressional pressure, pulled out of Somalia, and the episode spawned a whole new lexicon for policymakers spooked by the prospect of the United States getting ensnared in future military debacles. It was during the Somalia operation that a Washington Post columnist coined the term “mission creep” to characterize ill-defined ventures that could easily spin out of control. Meanwhile, “we don’t want another Black Hawk Down” became a reflexive catchphrase for policymakers wary of American intervention.

Just days after Clinton called off Task Force Ranger’s mission in Somalia, a U.S. Navy vessel anchored in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. U.S. and Canadian peacekeepers were deploying to train Haitian security forces for the return of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. But when the U.S.S. Harlan County was greeted by a throng of angry anti-Aristide protestors—some of whom fired shots in the air while others shouted “Somalia! Aidid!”—the ship weighed anchor and steamed out of port. A few months later, Clinton chose not to intervene in Rwanda where hundreds of thousands of Tutsis were being slaughtered by rival Hutus. His decision came after Hutu militia members killed and mutilated 10 Belgian U.N. peacekeepers in an echo of what Aidid’s forces had done in Somalia.

Throughout the 1990s, a profound risk aversion settled over civilian policymakers and, to a lesser extent, the military. When the U.S. did intervene militarily, such as in the Balkans, air power was the only real approach considered palatable. “No boots on the ground” became the mantra—a very different American way of war. Some have argued that the Bush administration’s aggressive response to 9/11 laid to rest the ghosts of Black Hawk Down, heralding a new dawn for America’s lethal Special Operations Forces. But even as the Bush administration launched major ground wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, it was still true that there was a deep reluctance to order commando operations in chaotic, out-of-the-way places.

One former top special operations commander recalls what transpired when a mission would be proposed that was “stealthy, surgical, and light,” the bread and butter of special ops: “We’d start with a recommendation of 50 men, but by the time it got briefed all the way up the chain, it would involve 10,000 men” and massive amounts of equipment and armor. Everyone wanted to make sure they’d be able to fight their way out of a Black Hawk Down situation. But then the plan would be cancelled because the Pentagon didn’t want to expend that level of resources.

During his first term, Obama repeatedly resisted putting “boots on the ground” in Somalia and personally invoked Black Hawk Down on more than one occasion, according to one of his closest military advisers. In September 2009, Obama and his advisers debated options for going after Saleh Ali Saleh Nabhan, a top Al Qaeda operative whom U.S. intelligence had identified in Somalia. The military wanted to capture him, but that would have required a potentially risky ground operation. Obama opted for a targeted killing, in which Little Bird attack helicopters strafed his car while he was traveling on an isolated road.

He did allow commandos to touch down in order to collect DNA samples so the military could prove Nabhan had died. But for most of the first term, Obama generally resisted the military’s requests to allow special operations forces to land on the ground—denying them, for instance, the ability to collect a target’s “pocket litter,” valuable intelligence they would likely find on his body or vehicle after the kill.

----

But what about those who fought in Black Hawk Down? On the surface it might appear that, for them, all these policy implications are very much beside the point. It’s an ancient warrior creed that the human experience of combat transcends politics. That attitude is typified by Hoot, the composite character played by Eric Bana in Ridley Scott’s movie version of the battle. “You know what I think,” he says when asked if it was a worthwhile mission. “Don’t really matter what I think. Once that first bullet goes past your head, politics and all that shit just goes right out the window.” Toward the end of the movie, Hoot reduces war to its most elemental quality: “It’s about the men next to you, and that’s it. That’s all it is.”

But that’s not exactly right. The warriors who fought in Mogadishu in some ways care about the politics in a more profound and visceral way than anyone else. If the most emotionally searing experience in combat is the death of a comrade in arms, then the most human impulse of the warrior is to ask: why? For all their expressions of pride in how they fought, some members of Task Force Ranger still are tormented by the belief that their brothers died in vain. They point to President Clinton’s decision to call off the mission after October 4, even though the objective of capturing Aidid had not been achieved.

“We had 18 lives committed to that mission,” says retired Col. Thomas Matthews, the air mission commander who guided the pilots of the 160th Nightstalkers in Mogadishu. “Once they decided to commit us, they needed to let us finish the job.”

Nothing seems to stir more ire than the fact that a few weeks after the battle, the Clinton administration entered into negotiations with Aidid, transporting him on a U.S. plane. Some members of Task Force Ranger were even assigned to provide security for the negotiations. “Don’t ask us to guard him,” says Mike Kurth, his lip quivering with anger at the thought of it all these years later.

Kurth and most of the veterans of Task Force Ranger are in no way trapped by Black Hawk Down. Still, many of the paths they’ve chosen have kept them connected to that formative experience. A number of them, like McKnight and Matt Eversmann—the Ranger played by Josh Hartnett in the movie—became motivational and public speakers, drawing on the experience to impart lessons about leadership and sacrifice and commitment.

All these years later, there isn’t a day that Black Hawk Down doesn’t flash through his mind.Other veterans of Black Hawk Down have become preachers and have drawn spiritual meaning from the experience. One former Ranger, Keni Thomas, became a popular country singer. His songs are filled with themes of war and patriotism. “Some say a hero is born to be brave,” read the lyrics of his song “Hero.” “But I’m here to tell you that a hero is a scared man that don’t walk away.”

Some Task Force Ranger vets left the military relatively soon after Black Hawk Down. William F. Garrison, the general who commanded the operation and was played by Sam Shepherd in the film, took full responsibility for the episode’s tactical failings. Shortly after the event, he hand-wrote a letter to President Clinton, Defense Secretary Les Aspin, and members of Congress explaining his actions but not making any excuses. His career was short-circuited and he retired two years later.

Garrison now lives on a farm in Hico, Texas, and has never given an interview about Black Hawk Down. He is revered by most of the troops who served under him in Somalia. During the reunion weekend, he attended a barbeque held at Ross Perot’s house in Texas. He apparently mingled easily with the members of Task Force Ranger and seemed happy to be there.

Many others who participated in Black Hawk Down stayed in the military and are just beginning to retire now. Eversmann, who served a 15-month tour in Iraq and retired in 2008, says that, before deployment, he obsessively tried to meet as many of the family members of the soldiers who served under him as he could. He never again wanted to have to meet them for the first time at their child’s funeral, as he had after Black Hawk Down.

A number rose thorough the ranks to become senior commanders in Iraq and Afghanistan. Captain Mike Steele was a company commander whose Ranger and Delta operators provided security around the crash site of one of the downed Black Hawks. They fought off thousands of militants throughout the night, but several of Steele’s men were killed. Later, according to a profile in The New Yorker, Steele was haunted by questions about whether his troops had been adequately prepared for the battle. The story suggested he would never let that happen again. As a result, some allege that in Iraq he created a culture of aggressive soldiering—one that may have gone too far. He was investigated for his role in the killing, by soldiers under his command, of four unarmed Iraqis. Though Steele was never charged, he was given a career-ending reprimand.

Chris Faris, a Delta Force operator in Mogadishu, rose to the pinnacle of the military’s elite forces. He is Command Sergeant Major to the Special Operations Command and, thus, the top enlisted adviser to Admiral William McRaven. In Somalia, Faris was part of the initial Delta assault team assigned to capture Aidid’s aides. After the first Black Hawk went down, Faris and his team moved toward the helicopter to secure the crash site.

On the way, they encountered a ferocious ambush. Earl Fillmore, a Delta operator two or three men up from Faris, took a round in the head, or, as Faris puts it, was “drilled in his brain housing group.” Seconds later, a soldier standing directly in front of him was shot. As Faris tended to his wound, he was shot in the back. The bullet didn’t penetrate his armor, but the kinetic force of the round caused hydrostatic shock and some internal bleeding. He was able to function, but he believed he was going to die. In a house the team had occupied, Faris held up his wedding band and said goodbye to his wife and his two small daughters. By now a calm had settled over him, a kind of primordial survival instinct, he believes. The only thing he feared was that if he died, his family would see his mutilated corpse dragged through the streets.

Faris survived and went on to have a storied career in America’s shadow wars, participating in or supervising thousands of classified missions in the world’s most dangerous places. Still, all these years later, Faris says there isn’t a day that Black Hawk Down doesn’t flash through his mind.

For him, the legacy of the mission is complicated. He appears troubled by those who weren’t there yet seem to have appropriated the legacy of the battle for their own political purposes. In 2009, he was part of a Pentagon team that proposed a secret counterterrorism mission in Somalia. At a planning session with senior Obama aides, a high-ranking State Department official said he was uncomfortable with the plan because he was worried it would lead to “another Black Hawk Down.” According to Faris, the official went on to say, “I’m the guy who had to fly into Mogadishu afterwards to clean up your mess.” (The official apparently did not know that Faris had been in Mogadishu.)

Faris began to sense the anger rising up through his body. As he started to get up, he felt Admiral McRaven’s hand squeezing his thigh. He got the message and sat back down. But he still boils when he thinks about it. What would he have told him, I asked Faris? “This guy didn’t know that when Earl Fillmore was killed his blood and brains were seeping out of his helmet,” says Faris. “Or that five hours later, moving his cold body to another position, rigor mortis has set in and his arms are sticking straight up into the air. He doesn’t know what a mess is.”

At the same time, Faris also knows that there are political lessons to be learned from Black Hawk Down: he speaks with conviction about never sending people into battle without a clear, attainable objective and without fully considering the consequences of those actions, something he says was not done before the battle in Mogadishu. “I thought the larger mission was bullshit,” he says. “Everyone died for absolutely no reason. It was wasted lives, wasted blood, and wasted treasure, and I’m angry about it.” Faris says that he vowed as a commander that he would never send a man or woman into battle unless he could tell their mother or father that their child did not die in vain.

In the end, the human toll of war cannot be separated from the larger political questions. They are intertwined and co-dependent. There was enormous heroism, valor, and tragedy in Mogadishu. “But,” says Andrew Bacevich, a professor at Boston University and retired Army colonel, “if you reduce war simply to a human story, you rob it of its political significance.”

“And war,” adds Bacevich, who lost a son in Iraq, “is ultimately a political act that has to be judged on that basis.” Many veterans of Task Force Ranger intuitively seem to understand that.

http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/10/09/black-hawk-down-s-long-shadow.html

A

Syrian soldier who was ordered to shoot civilian protesters and

imprisoned for refusing to do so speaks with Andrew Slater about life in

the Army and the crimes of the Assad regime.

Faced with certain death for desertion, and possible retaliation against their families, many conscripts have been put in the nightmarish situation of choosing between committing war crimes or being killed for trying to flee from a war effort they don’t support.

The excuse of “following orders” has its moral limits but to ignore the position forced on Syrian conscripts is its own form of blindness. Pretending that all Syrian soldiers are the same and equally culpable may be of some comfort if the decision to attack is made but it obscures the truth of the situation.

Most deserters living in refugee camps are now scarred by the brutality they witnessed and participated in, all for a cause they despised. There is no one to sympathize for their war trauma and most would like nothing more than to forget. You won’t hear from the unsuccessful deserters and dissenters of the Syrian ranks who have been executed anonymously, often casually by a loyal inner corps of junior officers and paramilitary, in untold thousands.

What follows is the first-person account of a former Syrian Army sergeant who was imprisoned for protesting orders to shoot civilians. I interviewed the man, whose name and identifying details I have altered to protect his identity, in late 2012 at a refugee camp in Northern Iraq. The interview, which has been edited for length and to preserve the voice of “Heen,” is a testimony to the evolution of events in Syria. In this first part, Heen describes his unit’s role in Dara’a, where the protests started and the war began and concludes with the events that led to his own arrest. Click here to read the second installment, in which Heen describes being imprisoned and fleeing Syria for a refugee camp in Iraq.

No one thought anything like this could ever happen in Syria. When I reported for my conscription in 2010 I thought I would do my two years of service without anything happening. Everyone said it would be bad, that they would insult you and hit you, but you could put up with it. I didn’t think I would ever see a war. Before the war I was a short-order cook in Zabadani, which is a beautiful tourist valley in Reef Damashq, near Lebanon. All kinds of foreigners came there for vacation, Khaleejis [Gulf country citizens], Lebanese, even Europeans. The mountains are very beautiful there.

After six months’ basic training in Khan Ash Shaykh, I was made a sergeant in charge of a BMP [a Russian-made armored personnel carrier] section. I was in charge of 14 privates in my unit, almost all young Sunni Arab guys. Kurds like me usually don’t get made sergeant. There were 16 sections like mine in my company with a captain in charge. There were no lieutenants in our unit, just musa’ada, or warrant officers, to help the captain.

Our captain had a very strong voice and a strong personality; he was an Alawi like most officers. He never sounded unsure of himself or conflicted about what we had to do in Dara’a. While he got his orders from the ameed, the colonel, mostly he had freedom to do anything he wanted in our assigned area: arrests, raids, shootings, destroying buildings.

Our unit was sent to Dara’a after the protests started in March of 2011 and our area was at the center of the problems because it contained the Umari mosque. There was no base for us in Dara’a so we took over an elementary school and turned it into our base. At the beginning we never worried about being attacked, we just had to deal with protests. We thought we would be there for a few weeks and then things would settle down.

When we arrived in Dara’a we were given strict orders to never speak with civilians there. Not during arrests, not breaking up protests, not on patrols. You would be beaten and sent to jail if you were seen speaking at length with civilians. We were told repeatedly that the protests were instigated by infiltrating foreigners, mostly supported by the U.S. and Western powers to undermine Syria, and that most of the protesters weren’t even Syrian. We were told they were Iranians, Afghanis, Americans, and Pakistanis forming these groups. As time went by it was obvious this wasn’t true and much of it didn’t make sense, but you couldn’t speak openly about it. At first, most of us just accepted that foreigners were behind it all.

In the beginning we were strictly prohibited from shooting at the protesters and the officers were very careful to avoid confrontation. At first we would just show up and surround the protests and hope that the show of force would convince them to disperse. Almost all of the protests started after Friday prayer at the mosques, because that is when all the men in the area gather together. We came to expect that every Friday we would have to break up a protest, but they grew larger and larger. When they became too large for us to arrest and disperse we began firing over the crowd or at unoccupied buildings nearby. When this didn’t work, my captain ordered me to fire a tank shell into a building near the protesters, but we didn’t kill anyone until later in April.

We heard that protesters had been tearing up posters of Assad, I don’t know where, and the colonel flew into a rage. I remember the protest that Friday outside the Umari mosque and at first we fired over the heads of the protesters. Then the colonel arrived at our position and told the captain to have us shoot into the crowd. The captain gave the order and he was the first one to shoot at them with his rifle. It wasn’t a free for all, but my soldiers all shot a burst or two into the crowd and everyone ran. Some shot more than others.

I remember it was a warm and mild day, sunny and clear. Within 10 minutes of the shooting starting, the streets were empty. After a while, people carefully came up to drag the bodies out of the street. I remember seeing the bodies lying in the street. Our chain of command told us that the eight we had killed in the protest had all been foreigners. None of us had hesitated to shoot, because we all believed it. We only realized over time.

Within my section I had a difficult time with my pro-Assad soldiers, my dirty guys. They were Sunni Arab but they came from tribes in Raqqah that were favored by the regime and they were ignorant. Some of them had clips of Assad’s speeches and pro-Assad songs on their phones they would listen to all the time. When we were waiting for protests to emerge, my worst soldier would lean on his machine gun and say, “Hurry up and come out so I can start shooting you.”

Most of my guys were not like this, but you had to act like you supported the government. As we shot at more and more protests and killed more and more civilians, I started to notice there were five other soldiers in my unit who realized that killing the protesters was wrong. Some of them would ask why we were shooting at people, even though in the end they had to do it like everyone else. Maybe there were more, but I knew that these five felt like I did. I told them discreetly that when the order came from the captain to shoot, to shoot near people but don’t hit them, so you seem like you are following orders.

One of my soldiers would shout curse words while he shot into the crowds and seemed to enjoy killing people. I had to be very careful around soldiers like this. We divided our time between living out of our BMP vehicle at an intersection which we were charged with guarding and at the school. All we had was a bed roll and a blanket, but it was very hot during the summer and impossible to sleep during the day. There were sinks and toilets in the school and tents in the courtyard, but we were still miserable.

I rarely got to speak with my parents on the phone, but the conversations were difficult. Everyone knows that the government could be listening, so you have to be very careful about how you talk. They were very worried about me. My father would speak in a coded way that let me know they were worried that I was doing bad things and that I was involved in the horrible things the Army was doing. I tried to reassure them, but after a while I got very angry. I couldn’t tell them about how impossible things were for me here. They didn’t understand what life was like for me and I couldn’t really explain it on the phone.

Officially school ended in July, but students stopped showing up in April, once the siege started. We had set up very strict curfew rules, and since we could not speak with the locals, communications were made by loudspeakers. Only women and children were allowed to leave the home between 5 and 7 in the evening to obtain essential things. To enforce this, people in the street were shot on sight, and Dara’a became a ghost city.

Only one of my soldiers was hurt in the fighting while I was there. One night, we were at a security position outside our BMP vehicle when someone threw a grenade at us from a nearby building. One of my soldiers was hit by fragments, but he lived. Much of the fighting was at night when the resistance could move around without being seen. There was a lot of mortar and RPG fire at us, but it was mostly inaccurate. Because units didn’t talk to each other there were lots of friendly fire incidents at night, 20 soldiers were killed that way while I was there.

When you are a soldier in Syria you must never let anyone think you are religious. You will immediately be suspected of sympathizing with the protesters. No one prays. No one fasts at Ramadan. No one has a Quran or suras from it. No one has tasbeeh prayer beads. You don’t even dare say 'Ya Allah' if you feel emotional about something. Later, when they were beating me in prison and I tried to swear to them, and I said ‘wallah’, they cut me off and said ‘Swear to us. We are your gods here.’

We were encouraged to abuse the people, even when it seemed pointless. We collected 2,000 motorcycles off the street and destroyed them. I ran over many with my BMP. The motorcycles are how poor people get around and live. We stole whatever we wanted from stores as we passed them. My soldiers’ favorite thing to steal was Marlboro cigarettes. One time we were ordered to drive our BMP into the front windows of a supermarket, it was very new and updated, and it collapsed the whole front of the roof. I don’t know why we did it. We were ordered once to shoot the water tanks on top of an apartment building, if you destroy the tank the building gets no water, and my gunner began shooting them all the time after that.